DSLR vs mirrorless cameras: which format is best, and why?

The DSLR vs mirrorless camera debate continues – we help you decide which is right for you

DSLR vs mirrorless is one of the first decisions you'll have to make when you're buying into a camera system – and it's one of the most important. While mirrorless is very much the way of the future, with almost all major manufacturers having refocused their efforts to mirrorless systems, DSLRs still have a place in photographers' hearts, and the decision between the two is not cut and dried.

After all, new DSLRs are still produced, sold and bought every day, and the second-hand market for DSLRs is very strong indeed, with some real savings to be had. After all, while the best DSLRs and mirrorless cameras differ in their construction and design, in terms of sensors and image quality there's a lot less in it. The big differences tend to be more in terms of physicality and handling, though there are technical differences in terms of the video capture and autofocus, which we'll get into.

Ultimately, neither choice is wrong – it's about what's right for you. With that in mind, this guide is designed to help you figure out which type of camera you're going to enjoy more and get more use out of – a mirrorless camera or a DSLR.

I am an independent photography journalist and editor, and a long-standing Digital Camera World contributor, having previously worked as DCW's Group Reviews editor. I have tested innumerable DSLRs and mirrorless cameras, pitting them against each other to get a sense of their strengths and weaknesses. As such, I'm ideally placed to help you figure out whether a DSLR or a mirrorless camera is right for you!

DSLR vs mirrorless: which is best?

Although mirrorless cameras can boast the latest imaging technology and more slender ergonomics, DSLRs have many more traditional physical qualities (including optical viewfinders) and old-fashioned virtues like longer battery life.

DSLRs and mirrorless cameras each offer a different shooting experience, so let's look at the key differences between them.

1. The mirror

DSLRs and mirrorless cameras both show the scene through the camera lens itself as you compose the picture, but the way in which they display it is completely different.

DSLRs use a mirror to physically reflect an optical image up into the viewfinder. You are looking at an optical image. When you take a picture, the mirror flips up so that the image can then pass to the back of the camera where the sensor is exposed to the image.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Mirrorless cameras operate differently by using the camera sensor's 'live view' to produce an electronic image, which can be displayed on the rear screen or in an electronic viewfinder, eliminating the need for a mirror mechanism. While this seems advantageous, there are some drawbacks.

Traditionalists often favor the optical viewfinder in DSLRs, and digital displays in mirrorless cameras consume more power, resulting in shorter battery life compared to DSLRs.

2. Autofocus

The key distinction is that mirrorless cameras use a single autofocus system for both rear screen (live view) and viewfinder shooting, while DSLRs require two separate systems. DSLRs rely on dedicated 'phase detect' autofocus sensors located at the base of the camera, behind the mirror. However, when the mirror flips up to capture an image, the AF sensor is no longer accessible.

Before live view was common, this wasn't an issue. But as the demand for live view shooting grew, and video capture became a commonplace feature, DSLRs had to adopt autofocus systems that utilized the image formed directly on the sensor. As a result, DSLRs still have one autofocus system for the viewfinder and a different one for live view.

In terms of performance, mirrorless cameras have not only caught up to DSLRs in autofocus speed but have also surpassed them, especially in frame coverage and tracking capabilities.

Mirrorless cameras can now be successfully used for fast-moving sports and action photography that once demanded a DSLR.

In fact, if you look at the capabilities of the hybrid on-sensor autofocus system in a camera like the Canon EOS R1, even DSLR diehards would have to concede that the separate phase-detect AF systems in DSLRs are dinosaurs by comparison.

There has also been a recent development in autofocus that is pretty much exclusively the domain of mirrorless cameras – AI-powered subject-detection autofocus. These intelligent systems are capable of recognising specific subjects in the frame – e.g. humans, animals, vehicles, etc – and prioritise locking onto and keeping hold of them. Users of advanced speedy cameras with this feature like the Nikon Z8 have essentially described as being like a 'cheat code' for wildlife photography.

Some models, such as advanced sports cameras like the aforementioned Canon EOS R1, can even be programmed to recognise the faces of specific individuals, with its Registered People function. This also lets you place these people in an order or priority, in the event that more than one of them enters the frame at the same time.

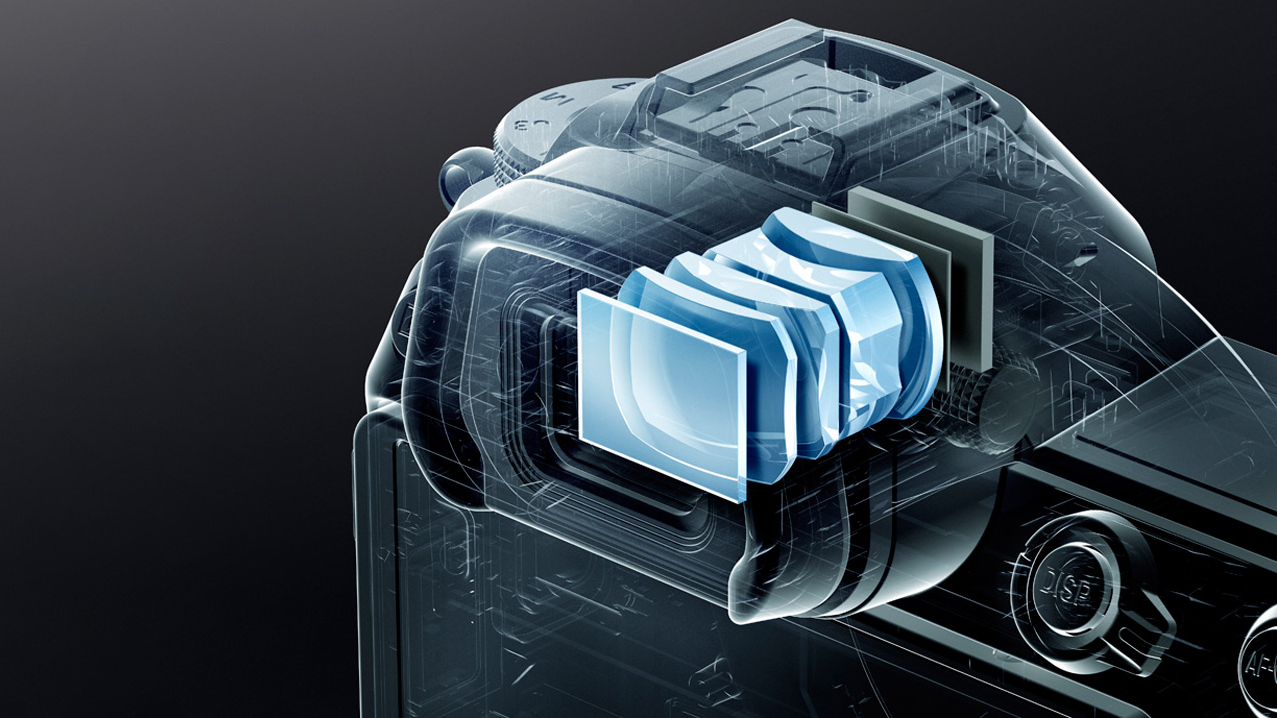

3. Viewfinders

The design of mirrorless cameras means that they need to use electronic viewfinders – and these have improved hugely in a very short space of time, similar to the way that modern phone screens are nothing like those of the past.

The latest and best electronic viewfinders available today (such as the Sony A1 II's 9.44 million dots and 240fps refresh rate) have such high resolution that you can hardly see the dots and they have a clarity that genuinely approaches optical viewfinders.

However, they can still suffer from lag, or 'latency' – a tiny delay between what the camera sees and what the screen shows. Viewfinder lag is less of an issue than it used to be, thanks to faster refresh rates, and the most recent area of focus for manufacturers has been in the blackout effect you would typically see when shooting continuous bursts of images.

Optical viewfinders typically have an advantage here that’s particularly relevant for sports and action photographers. There is unavoidable screen blackout in the camera’s burst shooting mode, as the mirror flips up and down between exposures, but this is rarely an issue – the key point is that there is no lag, and it’s much easier to follow a fast-moving subject with a high-speed DSLR like the Nikon D500 than it is with the average mirrorless camera.

That said, flagships like the Sony A1 II and Nikon Z9 have achieved blackout-free shooting, so technology is now compensating in the higher end models.

Electronic viewfinders can show a more clearly visible view of a scene in low light and have in-built zoom functions for precise manual focusing – two highly underrated benefits of electronic viewfinders. Because of their auto-gain light amplification effect, electronic viewfinders enable you to compose and shoot images in near darkness.

It's also worth pointing out that if you are a fan of vintage manual lenses that need to be used in stopped-down mode, a DSLR viewfinder will be way too dark – but a mirrorless EVF will be just fine.

4. Size

The most often claimed advantage of mirrorless systems is that they are much smaller than DSLRs. This is the main sell of mirrorless systems: the same size of sensor and image quality as offered by a DSLR, but without the bulk.

However, there are often trade-offs in making a mirrorless camera body so compact – such as battery life, the way a camera handles larger lenses (which, generally speaking, are little or no smaller than their DSLR equivalents), and how much space there is for external dials and buttons.

Small bodies also mean small controls, and users with larger hands may not find smaller mirrorless bodies easy to use. This extends to touchscreens, too, with virtual buttons and controls often too small for them to be keyed comfortably.

So although the Nikon D850 DSLR seems huge in comparison to today's full-frame mirrorless camera, many pro users will prefer its size because it's much easier to see and change camera settings – and because it balances better with big lenses…

5. Lenses

DSLRs still have an advantage for lens choice, simply because they've been around and supported for decades. Anyone that opts for a Canon EOS DSLR today has 30 years' worth of native optics to choose from, and many more when you factor in compatible third-party options. Nikon and Pentax are in a similar position with their DSLR ranges.

However, the development of new DSLR lenses has slowed dramatically. Canon and Nikon now put all their lens development effort into mirrorless lenses. Not only that, wider mirrorless lens mounts and shorter back-focus 'flange' distances have given lens designers a blank slate, and many new mirrorless lenses outperform older DSLR equivalents due to sheer physical and technological advantages.

It hasn’t taken Sony long to assemble an impressive range of lenses for its full-frame FE-mount mirrorless cameras (see our list of the best Sony lenses), for its full-frame line Panasonic has been smart enough to enter into an L-Mount Alliance with Sigma, Leica, and others, to generate a large and ever-growing lens range (see our guide to the best L-mount lenses).

Of course, Panasonic has history in this department, having previously entered into an alliance with Olympus (now OM System) for the Micro Four Thirds mirrorless system – the best Micro Four Thirds lenses rival any DSLR range in terms of sheer choice.

Nikon and Canon, meanwhile have been especially clever with their new full-frame mirrorless cameras. From day one, both produced a mount adaptor to use almost every current DSLR lens without restriction. And the best Canon RF lenses and best Nikon Z lenses are maturing at an incredible pace, offering almost every optic you could ask for.

It still takes time, though. Nikon's 'baby' DX mirrorless cameras, the Nikon Z50 II, and Nikon Z fc, still have only a handful of native APS-C lenses. The same is true of Canon APS-C cameras in the EOS R series, like the EOS R50 and EOS R100 – there are native lenses for this sensor size, designated RF-S, but not very many.

Fujifilm has developed its own native lenses for its mirrorless X system. While there isn't as much choice as there is with other brands, the best Fujifilm X lenses are known for their character, quality and beautiful bokeh.

In terms of size – there's not much in it. Some mirrorless makers have produced small or retracting lenses that do offer a size saving, but when lens makers produce mirrorless lenses to match the specifications and performance of DSLR lenses, they end up pretty much the same size.

The true exception comes in the form of the best Micro Four Thirds cameras, from OM System and Panasonic, whose sensors are so small that both the bodies and lenses are more compact than any DSLR equivalent.

6. Video

Mirrorless cameras have a considerable advantage when it comes to video, and that's why they comprise the best filmmaking cameras and the best hybrid cameras. First, their design makes them much better suited to the constant 'live view' required for video capture. Second, this is where camera makers are concentrating their video capture technologies and where you’re going to get the best video features and performance.

But let's not forget that DSLRs can shoot video, too. The Nikon D90 brought HD video to the consumer market in 2008, and in the same year Canon EOS 5D Mark II brought DSLRs into the professional videography and filmmaking arena.

For modern DSLRs, video capture is a standard feature. The Nikon D850, and Canon EOS 5D IV offer 4K video capture, while the Nikon D780 is still effective for video. Check out our best DSLRs for video guide for more.

Even so, when it comes to 6K and 8K capture, RAW or 10-bit video, high frame-rates and more, all the effort and development work is going into mirrorless cameras.

Sony and Panasonic have led the way with FullHD and 4K video, thanks to full-frame mirrorless cameras like the Sony A7S III and Panasonic S5 II, along with the trailblazing Micro Four Thirds video cameras, the Panasonic Lumix GH series. The Lumix GH4 was the first mirrorless camera to shoot 4K, and the latest Lumix GH7 is a fully comprehensive video shooter.

Mirrorless cameras like the Panasonic Lumix S1H and Canon EOS R5 C have received accreditation from Netflix for original content creation. And when it comes to 8K, mirrorless is the only way to go, with bodies like the Canon EOS R5 Mark II, Sony A7R V and Nikon Z8.

If you only need video occasionally a DSLR will be fine, but if you need to shoot it as an important (or the most important) part of your work, then it's time to go mirrorless.

7. Battery life

Even very basic DSLRs will happily offer 600 shots per battery charge, but the entry-level Canon EOS Rebel SL3 (aka EOS 250D) DSLR, for example, can capture up to 1,070 images on a single charge. The very best pro DSLRs can rattle off almost 4000 frames per charge, although this is admittedly with considerably larger batteries. With the Nikon D6, Nikon claims a stunning battery life of 3,580 shots – and twice that if the camera is used for high-speed continuous shooting.

Mirrorless cameras, however, fare far less impressively here, with around 350-400 frames per charge being the norm while some are a whole lot less. The Sony A7R III ushered in an extended 650-shot battery life almost double that of its predecessors. Since then, things have been steadily improving, and pro cameras like the Nikon Z9 generally hold their own in terms of battery life. Just like DSLRs, many can also be purchased with optional battery grips to extend their shooting lifespan.

Mirrorless cameras will inherently chew through more battery power than DSLRs. Either the LCD display or the electronic viewfinder is going to be on all the time when the camera is being used. Furthermore, the fact that most manufacturers try to make mirrorless models as small as possible means that their batteries are also small, which also presents a limit on their capacity.

Of course, you can buy spare batteries for cameras in both camps, so whether this is as great an issue or not is debatable. One advantage of mirrorless cameras, however, is that many now offer the option to charge through their USB ports, like the Sony A6400, which is very convenient when traveling, though this has appeared on DSLRs like the Nikon D780, too.

8. Dust

This is a difference between DSLRs and mirrorless cameras that never gets mentioned in the specs sheets but will have come to the attention of anyone who uses both camera types.

With mirrorless cameras, the sensor is much more exposed and much closer to the lens throat of the camera. With DSLRs, the sensor is right at the back of the camera and covered by the shutter and the mirror in front of it – the sensor is only exposed to dust when you take a picture (unless you shoot in live view).

Some mirrorless cameras seem much more susceptible to dust and other sensor debris than others. We have found some Sony cameras particularly prone to sensor dust, while Olympus, Panasonic, and Fujifilm cameras are not affected as badly. Almost all cameras have automatic dust-removal systems that 'shake' the sensor to dislodge any foreign matter, but some are clearly more effective than others.

However, while mirrorless camera sensors may be more exposed to dust, they are also much easier to clean. DSLR sensors are the very devil to reach with dust-removing gadgets and need a special cleaning mode that locks up the mirror and opens the shutter.

When to choose a DSLR

DSLRs are bigger, fatter, chunkier, and easier to grip. They handle better with telephoto lenses and they have more space for external controls, so you spend less time navigating digital interfaces and tapping at touchscreens – and their batteries last all day.

They also have optical viewfinders. Mirrorless users might not care, but DSLR fans would never swap the ‘naked eye’ viewfinder image of a DSLR for a digital simulation, no matter how good.

There’s another thing. If you’re on a tight budget you’ll have to work hard to find a mirrorless camera with a viewfinder for the same price as a DSLR – you will struggle to get a mirrorless APS-C camera with a viewfinder for the same price as a Nikon D3500 or a Canon EOS 2000D. DSLRs are still among the best cameras for beginners.

When to choose mirrorless

Mirrorless camera bodies are smaller and, if you choose carefully, you can get smaller lenses to go with them – though this only really holds true with the Micro Four Thirds format, as APS-C and full frame mirrorless cameras come with lenses as large as their DSLR counterparts.

If you’re an Instagrammer, influencer, vlogger or content creator a mirrorless camera like the Sony ZV-E1 or Canon EOS R50 is perfect. They’re small, light, and adaptable and have tilting/vari-angle screens that let you shoot from all sorts of angles. They’re great for both video and stills and can easily fit in an everyday bag.

If you’re a pro or semi-pro videographer, mirrorless is the way to go here, too. This is where all the video development in cameras, lenses, hardware, and accessories is happening. The Panasonic Lumix S1R II is a video-centric mirrorless model that's making inroads into the pro arena, and the Fujifilm X-T5 is a mirrorless camera with video specs that are currently out on its own in this price range.

There is one final paradox. You might say that the DSLR design is retro but, in fact, if you want a camera that looks and feels the way cameras used to, then a mirrorless camera is the way to go! See our guide to the best retro cameras to see why, as well as the best rangefinder cameras.

How we test cameras

We test cameras both in real-world shooting scenarios and in carefully controlled lab conditions. Our lab tests measure resolution, dynamic range, and signal-to-noise ratio. Resolution is measured using ISO resolution charts, dynamic range is measured using DxO Analyzer test equipment and DxO Analyzer is also used for noise analysis across the camera's ISO range. We use both real-world testing and lab results to inform our comments in buying guides.

Rod is an independent photography journalist and editor, and a long-standing Digital Camera World contributor, having previously worked as DCW's Group Reviews editor. Before that he has been technique editor on N-Photo, Head of Testing for the photography division and Camera Channel editor on TechRadar, as well as contributing to many other publications. He has been writing about photography technique, photo editing and digital cameras since they first appeared, and before that began his career writing about film photography. He has used and reviewed practically every interchangeable lens camera launched in the past 20 years, from entry-level DSLRs to medium format cameras, together with lenses, tripods, gimbals, light meters, camera bags and more. Rod has his own camera gear blog at fotovolo.com but also writes about photo-editing applications and techniques at lifeafterphotoshop.com

- James ArtaiusEditor in Chief

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.