110 cameras: the rise and fall of little film format that made photography easy

With APC-C film loaded into cartridges, 110 cameras sold in their millions in the 1970s and 80s

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kodak spent the best part of a century perfecting the point-and-shoot camera and arguably achieved its goal with the 110 Pocket Instamatic format. It wasn’t such a big hit with enthusiast-level shooters, but these film cameras sold in huge numbers for the best part of two decades.

At the height of its powers, Kodak was the inventor and innovator that shaped several aspects of photography for both amateurs and professionals. The objective was always to make photography more accessible to everybody via simpler processes and smaller, more affordable cameras… which, of course, would generate increased demand for film and printing materials. This was where Kodak made the profits it could plough into what was, at one time, the biggest and most sophisticated R&D facility in the world.

Beyond its many pioneering products, Kodak was also renowned for its engineering prowess. It all started with the creation of rollfilm – to replace glass plates – by George Eastman’s fledgling company in 1885, a couple of years before he came up with the name “Kodak” (which, by the way, meant nothing; he just liked the way it looked and sounded). This first rollfilm was paper-based and required a complex developing process to produce B&W negatives, so Eastman came up with the clever solution of packaging everything up into one product.

In the beginning

In 1888, the first Kodak camera was introduced – a simple box-type design – and it came preloaded with enough paper rollfilm to give 100 photographs. After it was finished, the camera was sent back to Kodak for the film to be unloaded and processed. The camera was then reloaded and returned to its owner along with the prints, prompting the famous Kodak advertising slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest”.

This arrangement eliminated any potential problems with film handling – a big risk at the time given few people understood the technology – but it was very expensive, limiting its appeal beyond wealthy early adopters.

Eastman continued to work on ways of making photography more accessible to the masses and the first step was rollfilm using a transparent plastic – or celluloid – base that was easier to process and, more importantly, when packaged in a light-proof cartridge, could be loaded and unloaded by the camera user.

The next step was a much more affordable, smaller and even simpler-to-use camera, and this arrived in 1900 in the shape of a new box-type model called the Brownie, after its creator Frank Brownell, whose own factory had been building cameras for George Eastman from the very beginning. A ‘brownie’ was also a mythical sprite, and this aspect of the camera’s name was used to help market it to children and adolescents – a first in the short history of photography. It worked, and around a quarter of a million ‘box Brownies’ were sold worldwide in the first year of production, no doubt also helped by the fact that it cost just a dollar (the equivalent of about US$28 today). It came pre-loaded with enough film for six two-and-a-quarter-inch square negatives, but a new roll only cost 12 cents. The No.2 Brownie of 1901 introduced 120 rollfilm that yielded 12 exposures per length.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The original Brownie camera was constructed from a reinforced cardboard material with a leatherette covering, and used a single element lens with a single-speed shutter and a fixed focusing range. The aperture was determined by the diameter of the lens and, initially, the viewfinder was a clip-on accessory. Despite the extreme simplicity, this camera – and its immediate successors – revolutionized photography for the masses, as it was reliable and delivered excellent results for the time. Its immense success would greatly influence Kodak’s thinking over the next three-quarters of a century… the challenge always being how to build a better snapshot camera. In one form or another, the box-type rollfilm Brownie remained in production until the end of the 1950s and the “Brownie” name was used until 1980, last appearing on a 110 format compact camera.

Instamatic formats

It’s worth noting here that Kodak didn’t invent the 35mm format for still photography – it was Leica and Zeiss Ikon that initially popularized it with their rangefinder cameras.

In fact, early on, Kodak considered the 35mm negative to be too small, limiting the potential for making enlargements. Even after it introduced its 35mm Retina series cameras in the early 1930s (which sold very well), the company remained unconvinced that the format would become popular and began looking at devising alternatives.

The first of these was 828 film, essentially 35mm film without the sprocket holes so that the whole area could be used to give a 28x40mm negative, 30% larger than 35mm’s 24x36mm. 828 film never really caught on and, as film technology advanced (much of it through Kodak’s R&D work), so did the performance of 35mm and, post-WWII, it was well on the way to achieving the popularity that Kodak had doubted was possible back in the 1930s.

However, problems with missloading the film or accidentally opening the camera back before rewinding – which fogged all the exposed frames – were emerging as major drawbacks of the cassette-based films for many consumers.

In the late 1950s, Kodak began work on the idea of repackaging 35mm film in a foolproof cartridge that could be simply dropped into the camera to load, and did not require rewinding at the end. In 1963, Kodak launched the Instamatic system and new 126 format film that was 35mm in width, but yielded 28x28mm images (typically masked to 26.5x26.5mm when printed, hence the ‘126’ designation) with a single sprocket hole per frame.

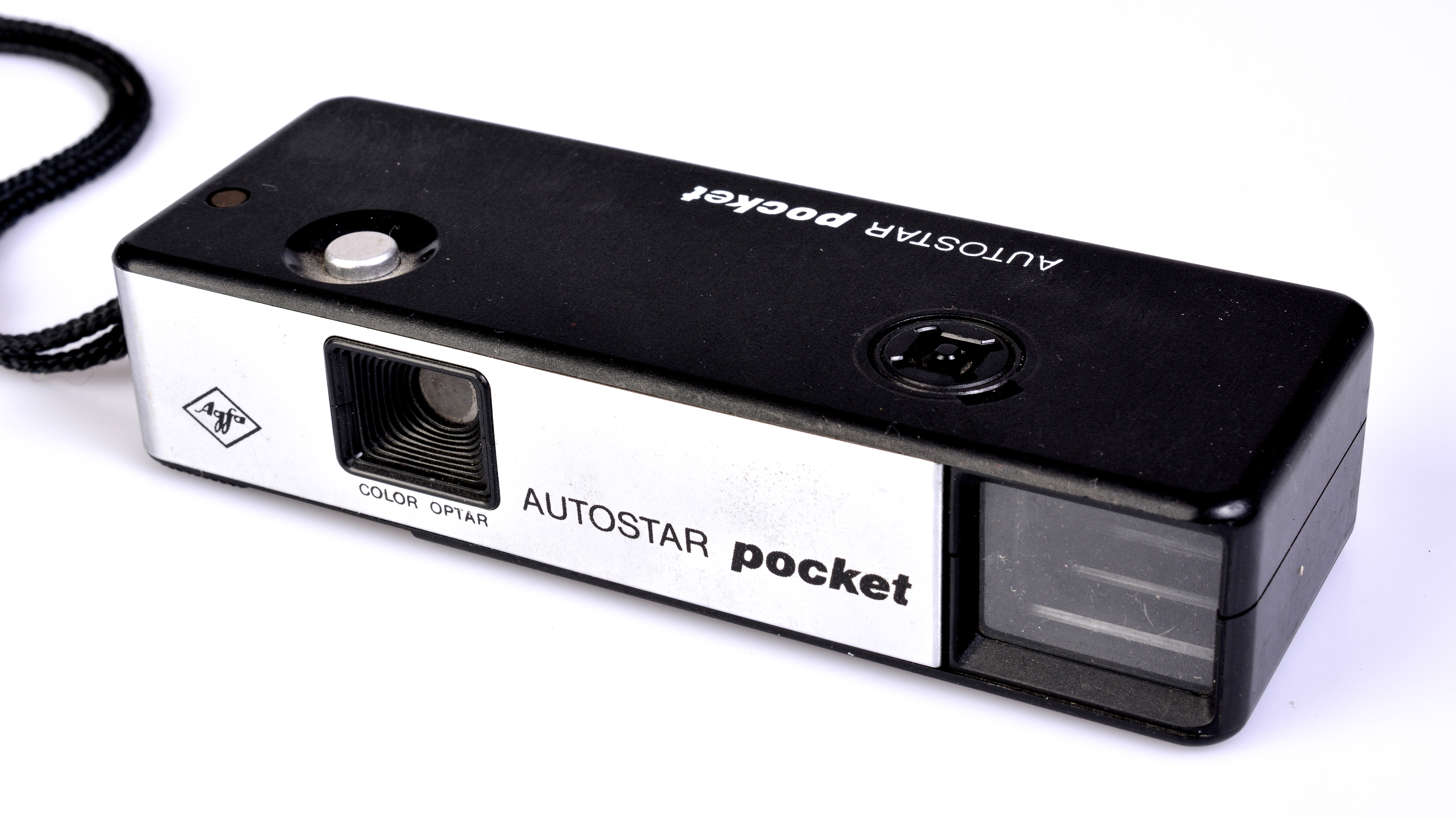

The Kodak Instamatic cameras were, in many ways, the 1960s equivalent of the box Brownie, utilizing the latest in plastics technology to create simple but strong and durable camera bodies. The 126 cartridge eliminated any handling of the film, and the system was an instant hit. Kodak alone sold over 70 million of its Instamatic series cameras during the 1960s and early 1970s, but it was adopted by a number of other camera manufacturers including Agfa, Konica, Minolta, Olympus and Yashica.

There were even a couple of 126 format SLRs, the most notable being the Zeiss Ikon Contaflex 126. However, 35mm continued to increasingly dominate in higher-end cameras as the more advanced amateurs – and obviously professionals – were experienced enough to avoid any problems with loading and rewinding the film. Kodak catered for these users through its extensive ranges of B&W, color negative and color transparency films, but thanks to its sheer volume, the snapshot camera market was arguably more valuable in revenue terms.

The birth of 110

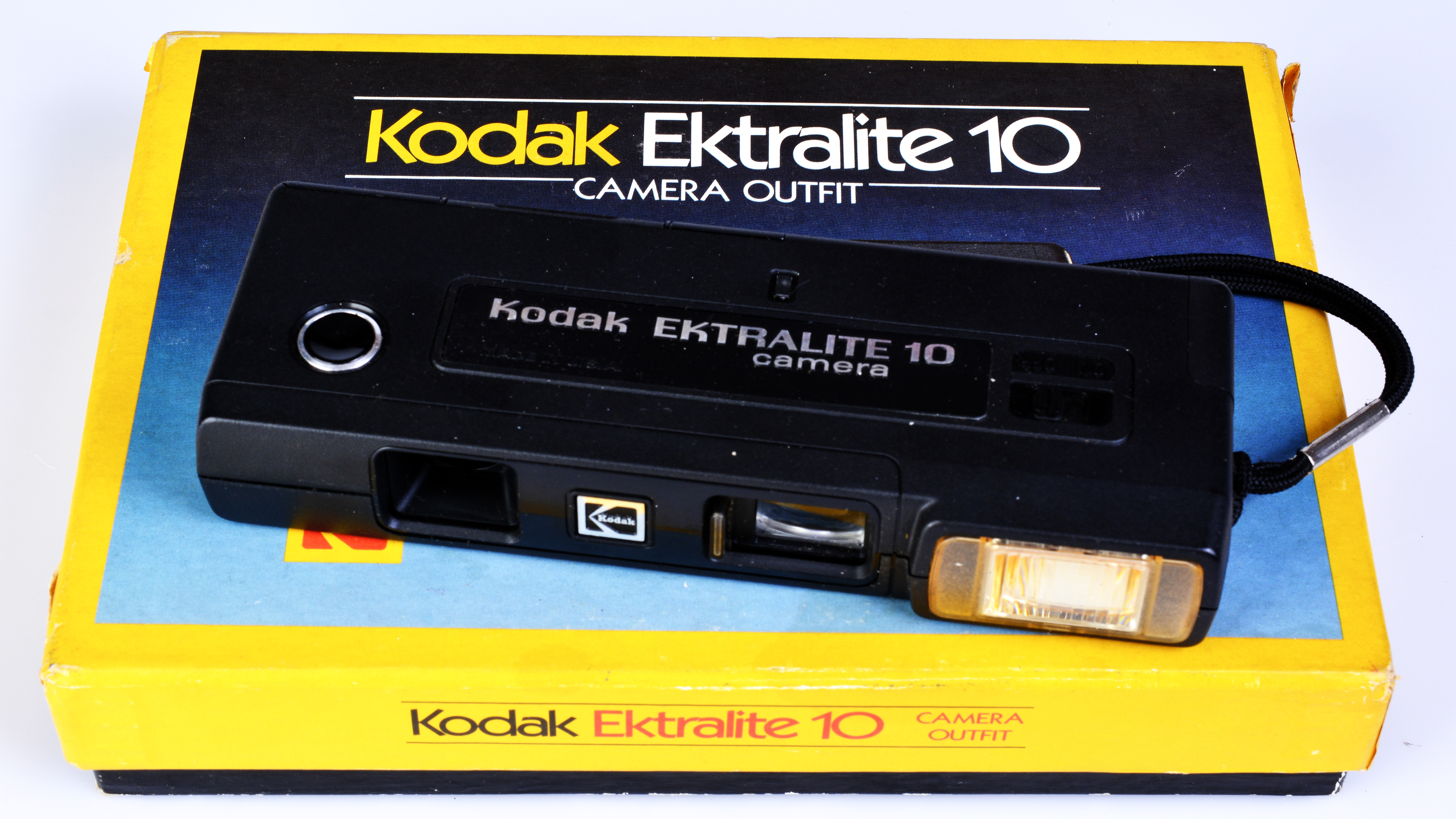

It was for the snapshooter that Kodak specifically devised the Pocket Instamatic system, launched in 1972, and otherwise known as the 110 format (not to be confused with the much earlier 110 rollfilm). The challenge, as always, had been to come up with a yet smaller camera and the continued advances in film technology now made it possible to consider a much smaller frame size.

Kodak turned to 16mm film that was, again, housed in an easy-fit cartridge to facilitate easy drop-in loading and eliminate handling errors. The image size was 13x17mm – again with one sprocket hole per frame – and which, incidentally, is very close to the imaging area of the Micro Four Thirds camera sensor.

The sprocket hole advanced the film, which automatically re-cocked the shutter and, in some cases, the cartridge was tabbed to tell the camera the speed of the film being loaded (which then set the shutter speed).

Kodak offered color negative film in ISO 100 and 400 speeds – although the earliest cameras had no provision for changing the film speed and were fixed at ISO 100 – and also, remarkably, Kodachrome 64 color transparency film. Kodak’s Ektachrome transparency film was available in 110 later on for easier access to processing.

Simplicity was again the key attraction of 110 cameras and the base models had plastic single-element lenses and single-speed shutters. But, as the format gained in popularity, more sophisticated designs began to arrive. For example, many early models had a fitting for the flash cube that had been popularized by the Kodak 126 Instamatic cameras (although it was an invention of Sylvania), but later models had built-in electronic flashes. Some also provided basic adjustments for focusing and exposure, and a number offered switchable lens settings for normal and telephoto focal lengths.

As the format matured, a number of more advanced models arrived which we’ll look at more closely shortly. Kodak’s long quest for a pocket-sized camera finally paid off and the 110 format was an instant hit – it’s estimated around 25 million cameras were sold in the first three years – so it was adopted by many more camera makers than had taken up licences for the 126 format.

Just about all the major brands were involved (the notable exceptions being Nikon and Olympus), and there were also 110 cameras from Chinon, Cosina, Hanimex, Minox, National (the brand name used by Panasonic for quite a number of years), Petri, Rollei and Vivitar.

Even Leica considered joining the party in 1974, but this camera eventually didn’t progress beyond the prototype stage.

Agfa, Fujifilm and Konica all joined Kodak in making 110 film (which made sense since all three also made 110 cameras) as did the Italian company Ferrania. Film made by these companies (with the exception of Kodak) was also sold under a variety of ‘house’ brands in various markets around the world.

Kodak discontinued 110 K64 in 1982 and finished making cameras in 1994, but continued manufacturing 110 color negative film in the format until around 2006.

Fujifilm had discontinued its 110 color neg films in 2004.

Subsequently, in 2012, the format was revived by Lomography which currently offers B&W, color negative and color transparency stocks. This is the only source of new 110 film cartridges today, but there’s plenty of expired stock available from various online outlets, but the results are likely to be unpredictable due to the color shifts that inevitably occur over time.

Promotional giveways

Because of their size and simplicity, which made them very cheap to mass produce, 110 cameras were frequently used as promotional and marketing tools by a diverse range of companies around the world, including Budweiser, Burger King, British Airways (one of a number of airlines to have airliner-shaped models), Coca Cola, Crayola, Dunlop, Fisher-Price, Kelloggs, Kit Kat, Kraft, Marlboro, McDonald’s, Pepsi Cola and Seven Up.

Perhaps not surprisingly, at one time or another, there were Barbie and Mickey Mouse themed models, but also 007, Cabbage Patch Kids, Hello Kitty, Punky Brewster, Snoopy, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Hulk Hogan, Where’s Waldo and many more.

While the 110 frame was small, it wasn’t beyond the capabilities of the color negative film technology of the day to deliver a reasonable result, many due to its exposure latitude. Obviously there was a limit to just how much enlargement was possible compared to 35mm, but the perception that 110 was poor quality was mostly down to the very rudimentary nature of many of the cameras that were made for it.

110 cameras get serious

However, the potential for a 110 frame to give a higher-quality print was recognised by a number of camera makers who created more sophisticated machinery for the format. Notable among these was the Fujica Pocket 350 Zoom launched in 1976, Minolta’s 110 Zoom SLR also introduced in 1976, and the Pentax Auto 110 – another reflex design – from 1978.

The Fujica 350Z stuck with the long, flat body configuration that was used for the vast majority of 110 cameras, but was the first to have a zoom lens – with a focal range of 25-42mm, equivalent to 50-84mm – with manual focusing, plus it offered a small selection of exposure settings, a cable-release socket and a hotshoe for fitting an external flash. These more advanced 110 cameras didn’t rely on the film sprocket hole to re-cock the shutter, allowing enterprising photographers to reload a spent 110 cartridge with whatever 16mm film stock they desired.

As an aside, 16mm film was popular for subminiature cameras that were made by, among others, Minolta, Mamiya, Rollei and Yashica during the 1960s and ’70s. The Minolta 110 Zoom also adopted a flatter body design, but it is a much bigger camera than the Fujica and much more sophisticated. For starters, it’s a reflex design – achieved via a fairly complex arrangement of prisms, mirrors and lenses – with a 25-50mm zoom (equivalent to 50-100mm). The lens is focused manually, but exposure control is via an aperture-priority auto control mode with a shutter speed range of 10-1/1000 second.

Interesting, Minolta adopted a completely different design for the Mark II model, which was introduced in 1979, and looked like a scaled down 35mm SLR but still retained a fixed zoom lens – now equivalent to 50-135mm – and also faster with a constant aperture of f/3.5 versus the earlier model’s f/4.5. It also gained full TTL metering, whereas the first model had a separate cell located alongside the lens. Minolta’s 110 SLRs were moderately successful, but it was clear that the smaller format certainly couldn’t compete with 35mm in the enthusiast sector.

Minolta didn’t give up on 110 though, and launched the Weathermatic A in 1980, which was an underwater camera that could be used at depths of up to five metres. Finished in bright yellow and with oversized controls that were easy to use when wearing gloves, the Weathermatic A sold very well and remained available even after Minolta introduced a 35mm version.

There ended up being a number of 110 marine or all-weather models – including from Sea & Sea and Hanimex – which is where the format’s cameras survived the longest.

Australia’s Hanimex was a huge supporter of 110 and, in addition to the marine Amphibian 110 MF (introduced in 1983 and watertight down to an amazing 45 metres), there were around 30 other models released over the period of a decade and sourced from a variety of manufacturers.

The Amphibian 110 MF was one of quite a few 110 cameras that were made in Japan, but a great many were manufactured in Hong Kong, Taiwan or China to keep the costs down even more. Sea & Sea used the same design as the Hanimex for its popular Pocketmarine 110 model.

Hanimex continued to market 110 cameras right up until early 1993, making it the last brand standing in the format as far as hardware was concerned.

Mini Marvel: Pentax Auto 110

Undoubtedly the most remarkable of all the 110 format cameras is the Pentax Auto 110, and it was also a remarkable piece of engineering for the time given its extremely compact dimensions. Pentax had always seen itself as the SLR company – it had certainly popularized the configuration in 35mm – so, in 110, it created not just a reflex camera, but an interchangeable lens reflex camera.

The Pentax Auto 110 was styled like a mini 35mm SLR, and a clever bit of engineering combined the shutter and the diaphragm arrangement in an assembly located just inside the lens mount. A comparatively simple – but ingenious – two-bladed design with triangular cutouts created the opening, and it eliminated the need to accommodate a diaphragm in the very small Pentax-110 system lenses... which meant every lens has an aperture range of f/2.8 to f/13.5. The shutter speed range is one second to 1/750 second, but exposure control is fully automatic so no manual settings are available, not even compensation settings.

The camera was launched along with three lenses – the 24mm standard (equivalent to 48mm), an 18mm wide-angle (36mm) and a 50mm short telephoto (100mm) – but later came a 70mm telephoto (140mm), a 20-40mm zoom (40-80mm) and a fixed-focus version of the 18mm. Additionally, independent lens maker Soligor produced a 1.7x teleconverter.

The Auto 110 system comprised two flash units, an autowinder and screw-thread filters for each of the lenses... the 24mm, for example, has a 25.5mm diameter fitting. Powered by a pair of AA-size batteries, the autowinder delivered continuous film advance at a modest 1.5fps.

The Pentax-110 24mm standard lens is truly tiny – about the size of a wine bottle’s screw cap – yet it still has a manual focusing collar and a distance scale marked in both feet and metres.

In 1983 Pentax introduced an upgraded camera body called the Auto 110 Super. The new features were a backlight compensation button and a self-timer, while the film advance’s lever’s action was revised to a single-stroke sweep that was a bit quicker than the previous need to make two 145-degree strokes. The focusing screen was also brighter, but the Super wasn’t around for very long at all and production appears to have ended sometime in late 1984 or early 1985, when it was obvious that SLR buyers wanted 35mm and the snapshot market wanted cheap point-and-shooters. By the end of the 1980s, the latter market was also being well served by 35mm compacts – which were becoming progressively smaller – and 110’s popularity had declined significantly although it survived for quite a while in disposable single-use cameras.

The marine models too remained available even after 35mm versions had been introduced, but even Kodak moved on, first with the Disc system – which really did push the available film technology with its tiny 8x10mm negatives – and then, in the mid-1990s, with the Advanced Photo System (APS).

Collecting 110 cameras

Nevertheless, by any measure, 110 was a huge success and arguably Kodak’s last big hit as neither Disc nor APS cameras sold in anything like the same numbers. Nobody knows for sure, given how many 110 cameras were made as promotional giveaways over the years, but the total would easily top 100 million units and a great many of these were very simple all-mechanical designs with fixed focus prime lenses and single-speed shutters.

Consequently, there’s plenty of very cheap buys to be had at garage sales, car boot sales and flea markets where the basic cameras are likely to be priced at under $5. However, expect to pay much more for the more advanced models such as the Pentax Auto 110 or the Minolta 110 Zoom Marks I and II which are all now considered quite collectible. They were made in much fewer numbers too.

A Pentax Auto 110 with a set of interchangeable lenses and accessories, such as the autowinder and the flash, are now selling for over $250. The several cameras used as promotional giveaways make a good collecting theme too – a largely affordable one – although some items are rarer now due to how many were simply thrown away, especially as users moved to 35mm.

Perhaps because of their cheapness and mostly basic designs, the 110 camera has been largely ignored by the writers of classic camera guides, compendiums and histories, but this really is an oversight given the format’s immense popularity – at least through the 1970s – and the significant sales achieved.

Bear in mind that film production carried on until the mid-noughties and Lomography obviously thought it was financially viable to revive the format a few years later and keep making film today. It’s nice to know that a $5 pick-up at a garage sale can still actually be used.

Most importantly though, the 110 cartridge format made photography more accessible to many, many millions and, consequently, no doubt recorded hundreds of millions of precious memories. For this reason alone it deserves acknowledgement of its place in the history of film photography.

Read more

Best film cameras

The best film

The rise and fall of the 35mm compact camera

The best film scanners

Australian Camera is the bi-monthly magazine for creative photographers, whatever their format or medium. Published since the 1970s, it's informative and entertaining content is compiled by experts in the field of digital and film photography ensuring its readers are kept up to speed with all the latest on the rapidly changing film/digital products, news and technologies. Whether its digital or film or digital and film Australian Camera magazine's primary focus is to help its readers choose and use the tools they need to create memorable images, and to enhance the skills that will make them better photographers. The magazine is edited by Paul Burrows, who has worked on the magazine since 1982.