The SLR revolution you forgot: How Auto Exposure changed film photography forever

As auto exposure control became a reality on 35mm SLRs, just about every manufacture tried to make it as affordable as possible, giving birth to a surprisingly long list of single-mode aperture-priority AE models

There are plenty of major milestones in the history of the 35mm SLR, particularly when it comes to the integration of increasingly more and more automation. Of course, there were a number of important mechanical milestones along the way, including the pentaprism-based viewfinder – which delivered a correctly-orientated image – and the instant return mirror along with automatic shutter recocking.

However, it was the incorporation of built-in metering which represented the first big step towards more convenient – and potentially more accurate once the measurements were made through-the-lens (TTL) – exposure control. Once stopped-down metering – which required that the taking aperture be preset – was superseded by open-aperture measurements, the next step was to use this communication from the lens to the camera body to facilitate semi-automatic exposure control.

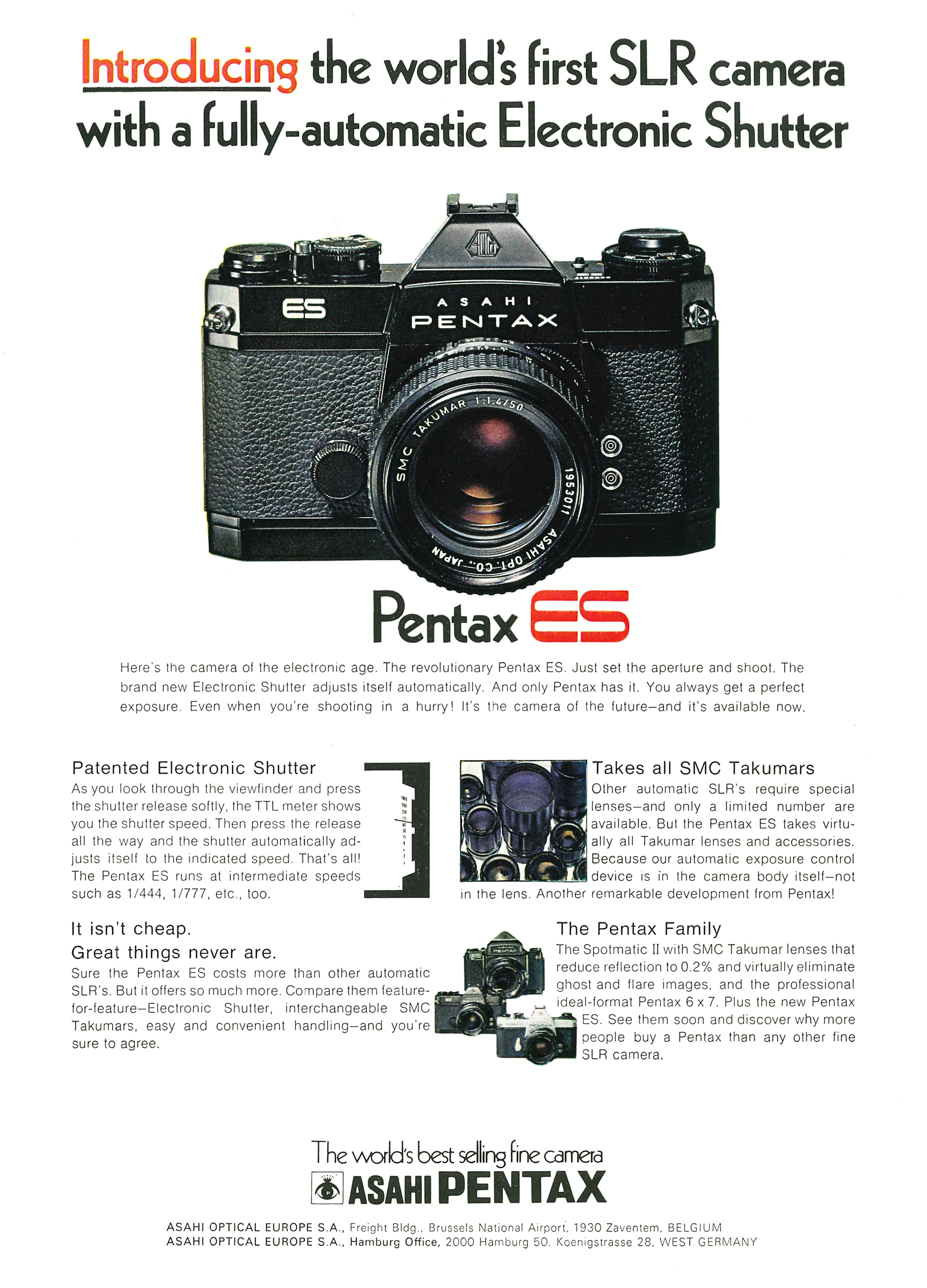

Asahi Pentax was the first to make the leap in 1971 with its ES model – standing for ‘Electro Spotmatic’ – which introduced the world to aperture-priority auto exposure control as an alternative to fully manual operation. Interestingly, Pentax achieved this while still retaining the M42 screw-thread lens mount which, for obvious reasons, made direct mechanical communication with the camera body more problematic… the main reason why many manufacturers adopted bayonet mounts during the 1970s.

However, the big deal with the ES was really its electronically-controlled focal plane shutter which enabled stepless speed setting. However, providing both open-aperture metering – also for the first time on a Spotmatic series model – as well as semi-auto exposure control also necessitated a new series of lenses that, by the by, also introduced advanced seven-layered multi-coating (called ‘Super-Multi Coating’ or SMC for short). With aperture-priority AE, the aperture is set manually on the lens and the camera then automatically sets a shutter speed to give a ‘correct’ exposure (at the selected film speed setting). As an aside, there actually was an earlier model called the Electro Spotmatic, (introduced in 1970) but it was extremely temperamental and subsequently only sold in Japan. Subsequently, after the problems – mostly related to the electronics controlling the shutter speeds – were ironed out it was decided to adopt the initials ‘ES’ as a fresh start.

It’s also worth noting at this point that shutter-priority auto exposure control had already been around since the mid-1960s with the notable pioneers being the Konica Autoreflex T and the Yashica TL Electro-X. Both were introduced in 1968 and, while there had been earlier examples, these were the first to introduce the configuration (notably, TTL metering and a focal plane shutter) which would subsequently be adopted by others including Canon. Fitted with the Servo EE Finder module, Canon’s pro-level F-1 – which was introduced in 1971 – gained shutter-priority auto exposure control, again also made possible by introducing a new lens mount, designated ‘FD’, which facilitated auto aperture control. The EF followed in 1973 and used essentially the same body, but with a ‘hybrid’ electro-mechanical shutter and shutter-priority AE built-in as the viewfinder wasn’t interchangeable.

Nevertheless, professional photographers would go on mistrusting camera automation well into the 1980s – although, in 1980, Nikon still introduced the F3 with a fully electronically-timed shutter and aperture-priority auto exposure control – but it had the potential to make 35mm SLRs much more appeal to first-time users. Traditionally aimed at pros and advanced amateurs, the market for 35mm SLRs was still comparatively small so automatic exposure control was seen as a way of enticing more people to upgrade from cheaper fixed-lens cameras. After all, selling more SLR camera bodies also meant selling more lenses and more accessories such as flash units. Affordability was obviously important and it made sense to delete manual exposure control altogether to keep things simple.

Advances in electronics – principally the microchip or microprocessor which was first used in the Canon AE-1 from 1976 – allowed for more compact designs that were cheaper to manufacture so the scene was set for a new breed of 35mm SLR which emerged in the latter years of the 1970s. The defining feature was that these cameras had a single exposure mode – mostly aperture-priority semi-auto control, but later there were some models with only fully-automatic programmed control – but they retained lens interchangeability and some models also accepted accessories such as an autowinder for motorised film advance. Just about every 35mm SLR maker at the time had one in its line-up, but most also retained a fully-manual mechanical model as an alternative for the budget-conscious buyer.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

This was the case with Pentax’s ME and MX which were both introduced in 1976 as a response to Olympus’s super-compact OM-1 and OM-2. Obviously, the challenge was to go smaller and lighter again which was achieved with both the aperture-priority auto ME and its mechanical (i.e. manual) stable mate. Incidentally, both models still retained metal bodyshells, although plastics were starting to be more widely used in the 35mm SLR construction. The ME’s electronic FP shutter had a speed range of 8-1/1000 second with one mechanical speed of 1/100 second – also the flash sync speed – plus the bulb (B) timer. If the batteries went flat mid-shoot that’s all you had to work with (and obviously no metering either). With battery power, the only way to adjust exposures was via +/-2.0 EV’s worth of compensation. There were the options of fitting an autowinder for 1.5 fps continuous shooting (a later version gave 2.0 fps) and a data back for imprinting the time and date on a frame. With the M series bodies also came new lens line-up called SMC Pentax-M which were also more compact and lighter weight than the original K bayonet mount models (now generally known as ‘K’ series lenses).

The ME set the blueprint for AP auto only 35mm SLRs so the Yashica FR II – which was launched in 1977 – had quite similar specs. However, it had a horizontal-travel cloth-curtain FP shutter versus the ME’s vertical-travel metal blades, with a speed range of 4-1/1000 second. The flash sync speed of 1/60 second was again also the sole mechanical ‘back up’ speed. It used the Contax/Yashica (C/Y) bayonet mount which had been introduced in 1975 with the Contax RTS system. Cosina’s CS-2 appeared in 1978 and had virtually identical specs to the FR II, but was another K mount model.

Many more brands jumped on the bandwagon in 1979 as Pentax replaced the popular ME with two models – the even cheaper (and simpler again) auto-only MV and the ME Super which added manual exposure control (but didn’t actually arrive until 1980).

However, by the middle of 1979, you could also have the Canon AV-1, the Nikon EM or the Olympus OM-10. All were significant departures for camera makers who had built their reputations on rugged higher-end pro or enthusiast-level 35mm SLRs. Nikon’s EM, in particular, caused quite a stir as it was very much no-frills – there was just a backlight compensation button in place of full plus/minus adjustments – and the top and bottom panels were plastic.

Of course, the EM certainly wasn’t designed for anybody who hated the idea of a cheap Nikon SLR, and it did have its plus points. The chassis was still diecast metal – the same material as the F3’s – so it was actually a lot stronger than it looked, and you could fit the dedicated compact MD-E motordrive for 2.0 fps, but it was also compatible with the later, 3.2 fps MD14. And, 45 years on, the EM’s size and simplicity have made arguably more popular as a classic than it was in its day.

Canon had already enjoyed huge success with the AE-1 – selling close to 1.2 million units in the first 20 months it was on sale – so it wanted to expand its A series line-up. The fully manual AT-1 was introduced in 1977 and the auto-only AV-1 in May 1979, both sharing essentially the same compact bodyshell as the hot-selling AE-1 (although the AV-1 is actually slightly smaller and lighter). In between came the multi-mode Canon A-1 (1978), the first 35mm SLR with microprocessor-controlled programmed (i.e. full auto) exposure control.

The AV-1 came about primarily because aperture-priority auto was preferred to shutter-priority in a number of important markets, most notably the USA. Its electronically-controlled shutter operates over 2-1/1000 second with flash sync up to 1/60 second and, again, with only a backlight compensation button for any form of correction. Keeping the same form factor meant that the AE-1’s accessories – including the Power Winder A and A2 autowinders – were compatible.

For Olympus, the OM-10 represented its first foray into the budget end of the 35mm SLR market so it was also kicked off a line of more affordable ‘double digit’ OM models. It has pretty much the same specs and features as the AV-1, but with the addition of depth-of-field preview which was provided on the OM system lenses. It could be fitted with the Winder 2 to give continuous shooting at 2.5 fps.

At the start of the 1980s, the auto-only 35mm SLR was becoming big business, convincing more brands to compete in the sector, including Fujifilm with the Fujica AX-1, Contax with the 137MD Quartz

and Mamiya with the ZE Quartz. All were launched in 1980 and, in the same year, Pentax introduced an updated version of the MV called the MV1 which gained a self-timer and regained a coupling for a power winder – either the 1.5 fps Winder ME or the 2.0 fps Winder ME II. The term ‘Quartz’ referred to the use of an oscillating quartz crystal to provide very accurate timing with electronic shutters.

The Contax 137MD Quartz was unusual in that it was an auto-only model from what was considered a prestige brand better known for packing in the features. It also had a built-in autowinder so, straight out of the box, it was more highly automated than any of its AP-only competitors. It was also a lot more expensive too, priced at $599 with a Zeiss Planar 50mm f/1.4 lens when it went on sale in Australia. Admittedly, you got a beautifully-made, all-aluminium camera body mated with a superbly sharp standard lens, but the Canon AV-1 was selling for

$299 with an f/1.8 lens, the OM-10 for the same money –again with an f/1.8 lens – and the Pentax MV for $279 with an f/2.0-speed standard lens.

Although Minolta’s SRM from 1970 was the very first 35mm SLR with a motorised film transport, in 1979 Konica pioneered the built-in autowinder in a consumer-level model with its FS-1 model. Contax was an early adopter with both the 137MD and 137MA, but it took a few more years before the ‘big five’ brands in 35mm SLRs followed suit – for example, the Pentax A3 in 1984 and Nikon’s F-301 in 1985. Incidentally, generally speaking, an autowinder only advanced the film automatically, but rewinding was still performed manually via a crank handle. A motordrive also rewound the film and this capability arrived in mainstream 35mm SLRs along with autofocusing, starting with Minolta’s historic Dynax/Maxxum 7000 model in 1985.

But back to the start of the decade. Mamiya’s ZE series was its last tilt at 35mm SLRs and, while it had been in the sector since the mid-1960s, it was much better known for its medium format cameras, including the mighty RB67 that was widely used by many professionals. The Z models were the first to use an electronic interface between the camera and the lens which meant, of course, a new bayonet mount which was designated ‘ZE’. The new lenses were either Mamiya-Sekor E or EF series. The line began in mid-1980 with the AP-only ZE, but this was quickly followed by the ZE-2 (which added a manual exposure mode), the multi-mode ZE-X (1981) and the manual-only ZM (1982) which turned out to be Mamiya’s last ever 35mm SLR. As another aside, the ZE-X was the most advanced 35mm SLR – in terms of exposure control – on the market and offered a choice of eight program lines along with a ‘Crossover AE’ mode which acted as both aperture-priority auto and shutter-priority auto depending on which setting you chose to adjust manually (similar to Canon’s current ‘Flexible Priority’ mode). Furthermore, if you selected a manual value that was beyond the EV range available with the corresponding automatic settings, the crossover system simply overrode it and went for something that would deliver a good exposure.

As the 1980s progressed, multi-mode 35mm SLRs were becoming more affordable and there were the first steps into autofocusing, but there was still a place for budget-priced models that were as simple to use as possible. Praktica – the brand born out of the East German part of Zeiss Ikon – built affordable mechanical reflex cameras with the M42 screw mount before introducing its electronic B series in 1979. Of necessity, these models also switched to a bayonet lens mount (a proprietary fitting with three contact pins) and there was subsequently a line of aperture-priority auto models, starting with the B100 Electronic in 1981 and ending with the BX10 DX in 1989.

Electronics and plastics enabled the B series – and, later, BX series – Prakticas to be a lot more compact and lighter than their heavy-metal manual cousins, and they were pretty well-made if lacking a bit of finesse in the fit and finish. Nevertheless, the B100, for example, had a metal-blade focal plane shutter with a speed range of 1-1/1000 second, +/-2.0 EV of compensation, aself-timer, an LED viewfinder display and connections for fitting an autowinder. Subsequently, the BCS (1988) lackedboth the winder connections and the exposure compensation facility, and the BCC (launched later in the same year) also lacked a self-timer, making it very much a no-frills 35mm SLR. However, curiously, there was a version of the BCC with depth-of-field preview, a feature not offered on any previous AP-only model.

The restyled BX series was introduced in 1987, adding DX automatic film speed setting and TTL flash metering along with a revised shutter design with slow speeds down to 40 seconds. The auto-only BX10 DX had a very short model life with production ending less than a year after its introduction in June 1989. However, it did have exposure compensation, a self-timer and connections for the new BX Winder which delivered 3.0 fps continuous film advance.

While the Praktica name is still around, by the start of the 1990s, VEB Zeiss Ikon Jena – which had also been known as Pentacon since 1959 – was suffering the free-market economic realities that followed German unification and it finally ceased production in June 1991. The remains of the business was purchased by Schneider-Kreuznach and so the last-of-the-line Praktica BX20S actually remained in production until 2001.

It’s remarkable that a humble camera design which had its origins in the late 1970s was still selling in sufficient numbers to justify maintaining production over two decades later. And, by then, 35mm SLRs had reached the height of automation with advanced autofocusing, exposure metering and very fast (for film) motordrives.

For the Japanese camera makers, the autoexposure-only 35mm SLR had served its purpose by the mid-1980s as it was then possible to manufacture less expensive multi-mode models. Before this, though, there were a couple of notable variations on the single mode theme with, first, the Konica FP-1 Program in 1981 and then the Canon T50 in 1983, which both had only programmed – i.e. fully automatic – exposure control. The T50 also had a built-in autowinder, but the idea of a point-and-shoot 35mm SLR reached its peak with the T80 (1985), which also had autofocusing and motorised film rewinding so it was entirely automatic in its operation (although there were various overrides, including for focusing).

The T80’s AF predated the EOS system by a little under two years and used special AC series FD mount lenses – of which there were just three – with built-in focusing motors powered from the camera body. These motors and the focusing drivetrain made the AC lenses quite bulky which is obviously something Canon had resolved by the time the first EF mount lenses arrived, but the EOS system configuration was the same as that of the T80 whereas just about everybody else initially opted to drive their AF lenses from the camera bodies. However, history records that the ugly-duckling T80 didn’t sell especially well and production ended after only 14 months.

Camera automation continues to become more and more sophisticated – especially now that AI-generated algorithms are at work – but it all started with exposure control; the very essence of photography. The aperture-priority-only 35mm SLRs not only kept things simple, but also made the convenience of auto exposure control more affordable for anybody who was ready to move on from a basic snapshot camera. It was a comparatively short-lived period in the evolution of interchangeable lens cameras, but a significant one nonetheless and many of these models undoubtedly started a lot of amateurs on the road to a lifelong hobby and possible even a career.

It’s telling that, today, the combination of simplicity and flexibility embodied in cameras such as the Nikon EM, Canon AV-1, Olympus OM-10 or the Pentax ME is still appealing for digital-era photographers getting involved in 35mm film photography for the first time.

Check out the best film cameras you can buy today (and the best 35mm film to use with them)

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.