Golden hour is more like “the golden five seconds” on the International Space Station. Astronauts Don Pettit and Matthew Dominick share the challenges – and hacks – of photography in space

In a captivating podcast, two NASA photographers and astronauts just shared what it's like to take photographs in space

Photographers often wish for more time to shoot the sunset – but the astronauts aboard the International Space Station get to witness 16 sunsets and sunrises a day. The problem? Golden hour is more like “the golden five seconds,” says astronaut, chemist, and renowned space photographer Don Pettit.

Pettit recently joined fellow astronaut and photographer Matt Dominick on NASA’s Houston We Have A Podcast to chat about the intersection between art and science and the challenges of taking photographs aboard the ISS.

While some challenges, like a five-second golden hour, are exclusive to only those photographers lucky enough to set foot (or is it float?) aboard the ISS, the discussion between the two astronauts and podcast producer Joseph Zakrzewski is filled with inspiration and insight even for photographers who photograph the stars with two feet planted firmly on the ground.

Knowing when to keep shooting…and when to put the camera down

Pettit may have 60 terabytes of RAW images from one eight-month stint aboard the ISS, but the astronaut cautioned that some experiences are best when not viewed through a viewfinder. Rocket launches are one example, Pettit says, especially for those standing a few miles away with an iPhone when dozens of professional photographers will be capturing the same launch. Sometimes, Dominick added, the astronauts will just witness phenomena like the aurora from the cupola without cameras.

“There’s something extraordinarily human with you just take in the event where you’re not worried about f-stop and shutter speed and composition and looking through the lens of a camera,” Pettit said.

He added that it’s possible to both witness something with your own eyes and capture images, recommending setting a camera up on a tripod during an eclipse so that you can both photograph it and experience the event without looking through a viewfinder.

But Pettit, who applied to astronaut training four times over twelve years before being accepted into the program, said that some images take “many, many tries.”

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

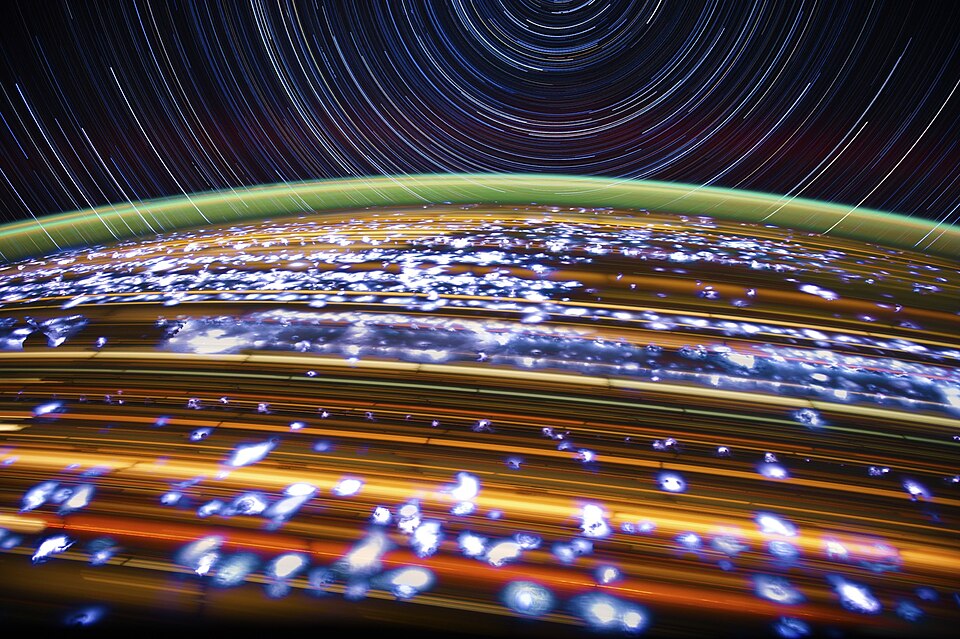

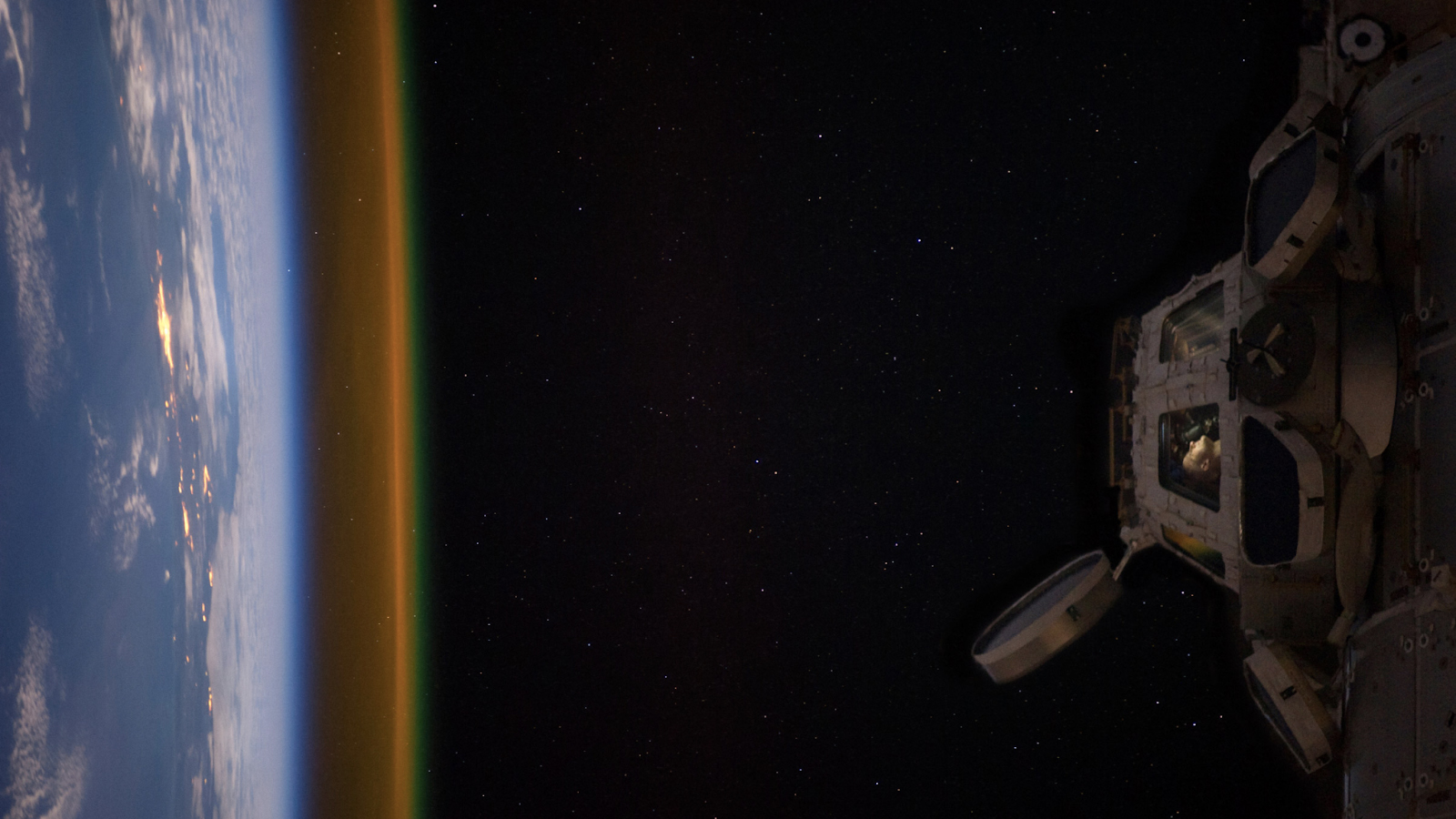

One such image is when Dominick photographed Pettit viewing the Earth from the Cupola, looking towards the Earth at night. The duo said that it took several tries to get the lighting in the Cupola to match the city lights on Earth so that Pettit’s face didn’t end up overexposed.

Use a time-lapse to pinpoint the best time to shoot

The ISS orbits Earth every 90 minutes, which means the astronauts aboard witness 16 sunrises and sunsets a day. While that means the astronauts could have a second chance at getting a shot on the next rotation, it also condenses the best time to get a certain lighting down to mere seconds, rather than a “golden hour.”

But Dominick has a hack for figuring out when the best time to shoot something is – while actually still doing his official job aboard the ISS as a flight engineer. The trick? Time-lapses.

“I spend a lot of time trying to figure out, when is that lighting just right? And instead of just staring out the window for 90 minutes when I’m supposed to be doing my actual job, I would set up a camera to take a picture every, you know, maybe quarter second every half second,” Dominick explained. “...[then] I can go watch a 90-second video and find what part of the orbit the lighting is perfect, and then set up the camera and the right exposure for the next lap, and capture a bunch of brilliant stills.”

Find the best ISO, underexpose, and use bracketing for challenging exposures

With one sunrise every 90 minutes, the photographers aboard the ISS need to adapt to changing light conditions far faster than on Earth. Dominick shared three bits of advice on getting the shot in the extreme dynamic range of shooting out a window of the ISS.

“One of the things we learned, or I learned, specifically on orbit early, was picking an ISO that has more dynamic range than others, and accepting some of the noise as a result or not.”

A camera’s ISO setting will influence how much dynamic range the sensor captures. According to DCW’s lab tests on the Nikon Z9, the camera that the astronauts mentioned in the podcast, the best dynamic range comes at ISO 1600 and under.

Both Dominick and Pettit recommend underexposing the image because once an image’s pixels are overexposed to white, there’s no information that can be recovered from that region later. One trick for ensuring the exposure is just right is to use bracketing and shoot 3-5 shots at once, all with a slightly different exposure.

Getting tack sharp stars in astrophotography…with a piece of tape?

Much like photographing the night sky from the ground, getting sharp stars requires manual focus. One hack that Pettit uses is to use magnification on the camera’s LCD to get the stars sharply focused, is to use tape on lenses, where the focus can easily be bumped out of place when moving around to adjust the composition for another shot.

“I would take a piece of Kapton tape, and I would tape it in that location, because it’s so easy to bump the focus ring inadvertently when you’re moving the camera around to get the composition you want,” Pettit said. “And just change the focus slightly, and then the stars aren’t pinpoints anymore. And I gotta have stars that are pinpoints, or I’m not happy.”

Pettit says the tape hack is also great when planning to photograph a comet. There’s no time to adjust focus once the comet comes into view, so focus ahead of time on the stars and lock the focus in with tape. (Some lenses have a lock switch built in that will also lock the focus ring in place.)

Knowing how to use your camera, well before the moment you actually need to use it

Both Pettit and Dominick picked up photography from their parents. Pettit said his mother was a photographer who had some photographs published in Life Magazine, and he got a Kodak Brownie camera when he was around six or seven years old. Similarly, Dominick’s father was a professional photographer for the Air Force.

“It’s photographs and memories after your mission,” Pettit said. “And if you don’t have the photographs, and you just have the memories. And you don’t want to find yourself on orbit picking up the camera and saying, ‘Now, how do you turn it on?’ You need to know how to use your equipment, and you need to practice way before you even get close to a rocket.”

The full interview with Pettit and Dominick is available directly from NASA as well as on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud.

You may also like

Browse the best lenses for astrophotography or the best tripods. Plus check out the best astrophotography events in August 2025

With more than a decade of experience writing about cameras and technology, Hillary K. Grigonis leads the US coverage for Digital Camera World. Her work has appeared in Business Insider, Digital Trends, Pocket-lint, Rangefinder, The Phoblographer, and more. Her wedding and portrait photography favors a journalistic style. She’s a former Nikon shooter and a current Fujifilm user, but has tested a wide range of cameras and lenses across multiple brands. Hillary is also a licensed drone pilot.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.