Are 360-degree cameras useful for astrophotography? I took one on a hunt for the Northern Lights to find out

The “shoot first, edit later” philosophy behind 360-degree cameras should, in theory, make them ideal for imaging the night sky. Here’s how the Insta360 X5 performed in Churchill, Canada

Can 360-degree cameras be used in the dark to image the night sky? Astrophotographers have been using circular fisheye lenses to capture the Milky Way for decades, while astronomers regularly employ 180-degree (whole-sky) lenses to image fleeting “shooting stars” and, in the case of the Swedish Institute of Space Physics (IRF), produce an all-night timelapse of auroras (see this example). Whether consumer 360 cameras — essentially two 180-degree fisheyes mounted back-to-back — are capable of true astrophotography is another matter.

In 2025, two key models appeared with improved low-light potential: the Insta360 X5 and GoPro Max 2. Both claim 8K resolution and AI-assisted noise reduction. With the GoPro Max 2 unavailable at the time, I took the X5 to Churchill, Manitoba, to see how it performed under the Canadian Northern Lights.

Why use a 360 camera for astrophotography?

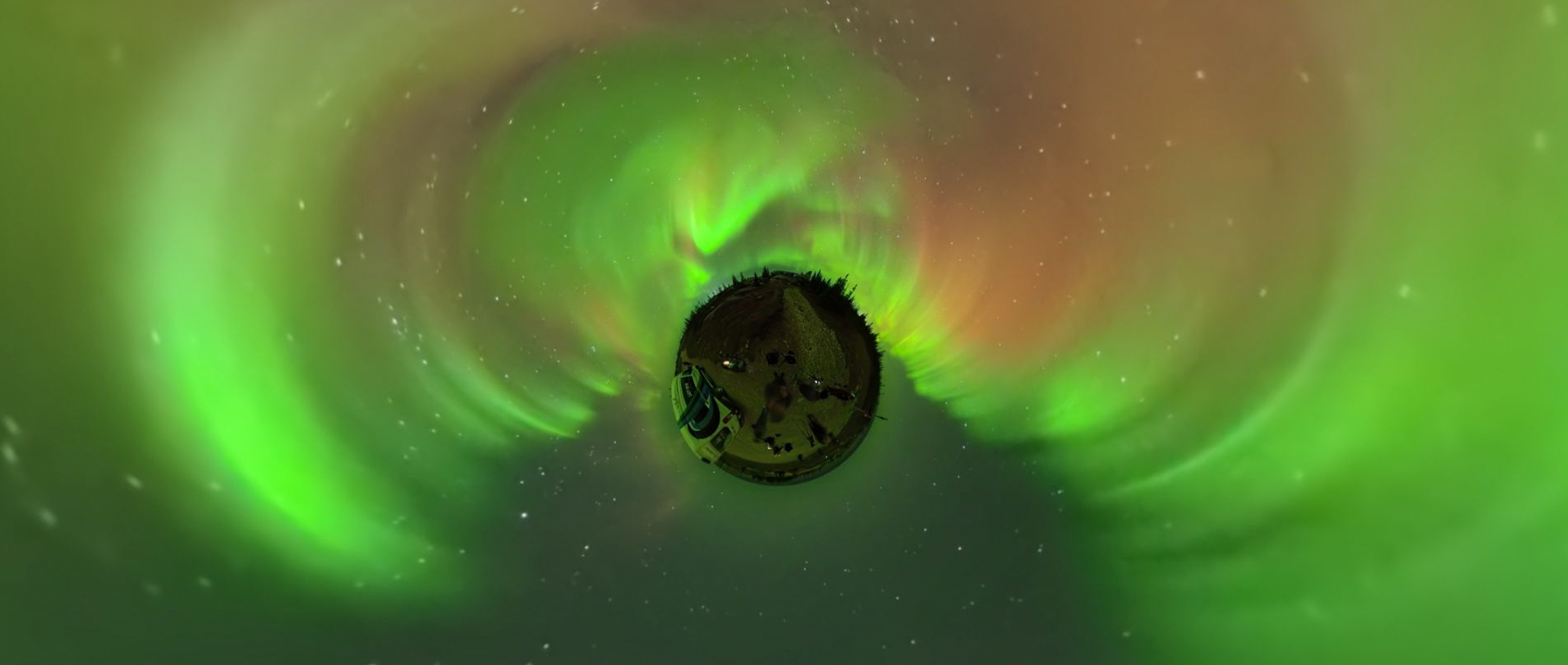

The immersive nature of 360 cameras is immediately appealing. By capturing the entire sky and landscape, they open new possibilities for creative storytelling — linking the cosmos above with the scene below. If astronomy is about what happens above the horizon, and astrotourism is about what happens beneath it, then 360 astrophotography bridges the two beautifully.

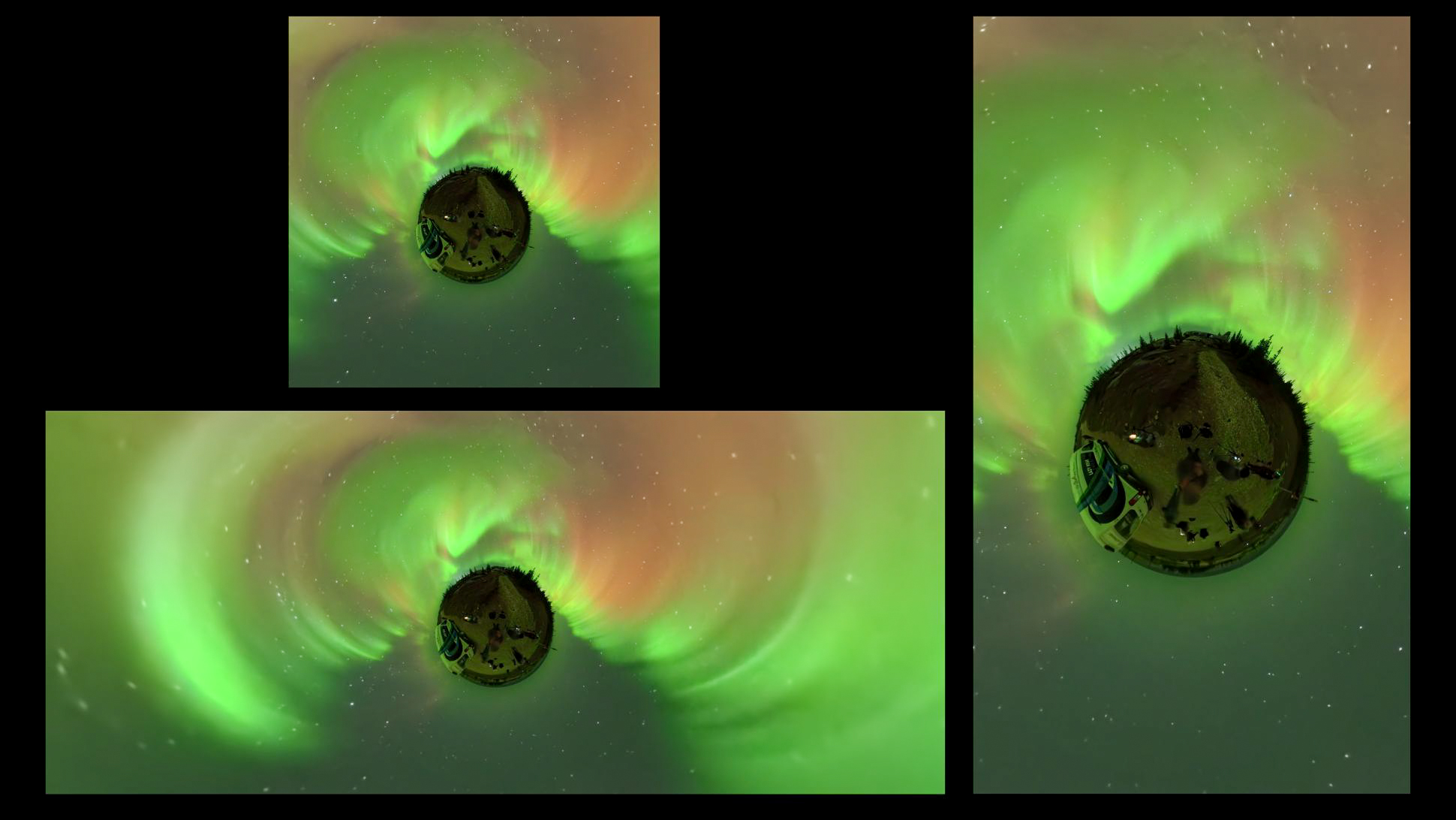

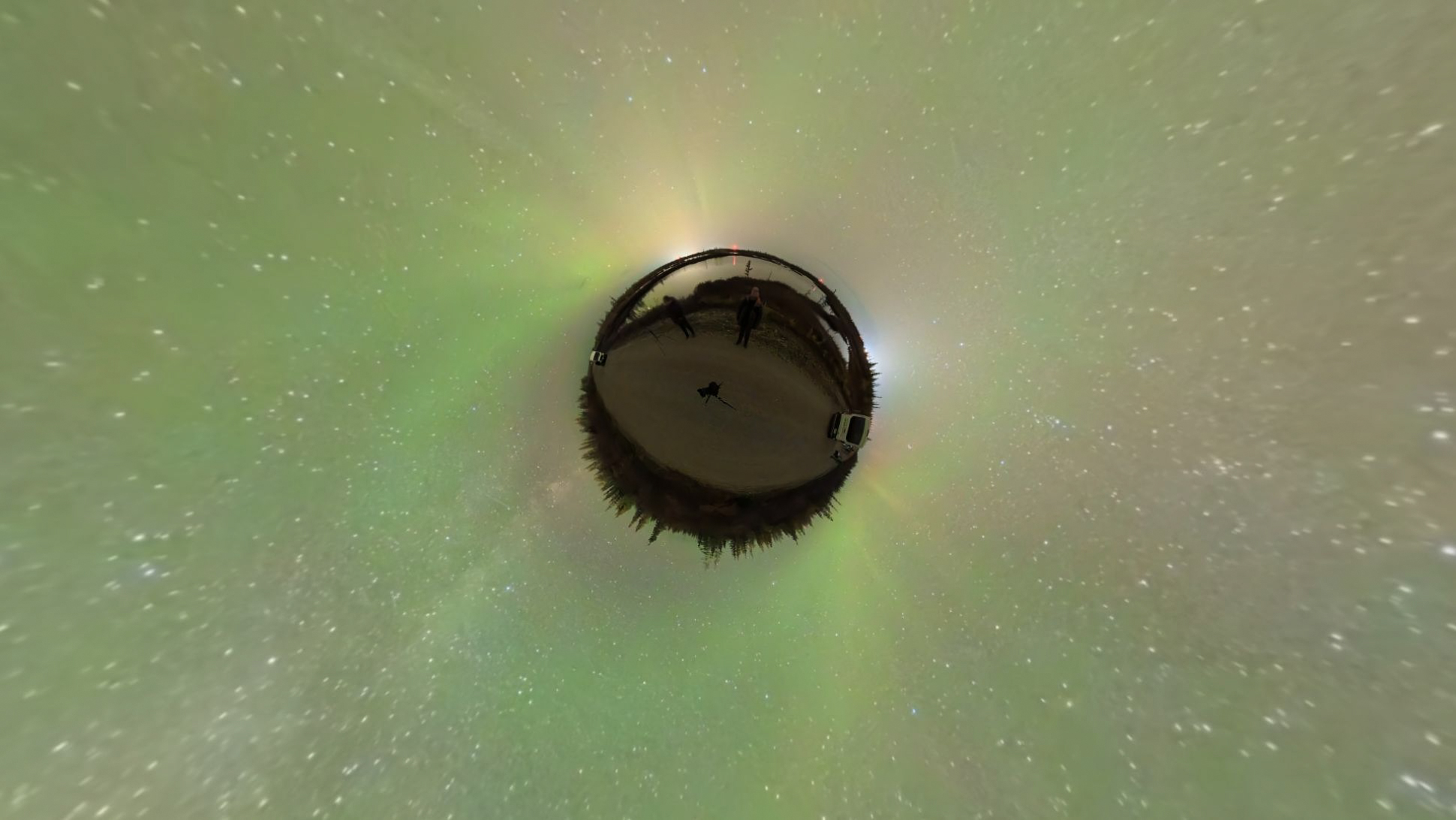

The best thing about 360 photography is that you can reframe your shot later — zoom in or out, switch from vertical to widescreen, or highlight any element that happened to be in view. You can go “tiny planet,” panoramic or all-sky — the choice is yours.

Limitations of 360 cameras

The most common misunderstanding about 360 cameras is their effective resolution. Even though 8K sounds impressive, that’s across the entire 360° sphere — effectively around 4K per hemisphere. The Insta360 X5’s stills measure 11,904 × 5,952 pixels (about 70.9 MP) in a 2:1 equirectangular format, but reframing inevitably reduces detail.

Sensitivity is another challenge. Consumer 360 cameras use small smartphone-class sensors. They perform well in daylight but struggle in darkness, producing grainy, low-contrast images even with long exposures.

The X5’s PureVideo mode (8K 30 fps) is designed to enhance low-light footage, but in my tests during a new moon, it wasn’t sensitive enough. That’s a shame because it’s something the newer full-frame mirrorless cameras can handle. Happily, the X5’s 1/1.28-inch sensor handled long-exposure stills far better.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Field test in Churchill

During my three nights in Churchill, the moonless night skies were clear, with the late-season Milky Way bright — and the aurora brighter. At 58 degrees north, Churchill is permanently under the auroral oval, so even if there’s no significant geomagnetic activity forecast, the aurora are often visible after dark. On the final night of the trip, Kp5 conditions ensued, causing the night skies to come alive with intense aurora for about two hours.

With the Insta360 X5’s battery fully charged – and good for about three hours – I took it out first to a lonely lake road, and then to the iconic “Miss Piggy” air crash site close to Churchill Airport … where polar bears are often spotted (there was an armed guard with a gun, and a minibus with open doors, nearby at all times!).

I set up the camera first on its invisible selfie stick, which extended to 9.8ft. I mounted it on a small tabletop tripod — and it immediately fell over in the wind during one of the first shots I took (the camera wasn’t damaged, but its casing was scuffed). I quickly re-mounted it on a tough full-size tripod.

I also took the opportunity, between auroras, to apply (several) Band-Aids over the very bright and incredibly annoying blue flashing lights on each side of the Insta360 X5 that accompany a countdown to a long exposure. If there is an option in the settings menu to switch those off, I didn’t have time to look for it.

360 settings at night

After testing, my preferred settings — under a new moon — for stills were: PureShot, ISO 1600, 10-second exposure, auto white balance, and no exposure compensation. Under darker or brighter conditions — for example, during quarter or gibbous moon phases, or with less intense aurora — you’d need to adjust accordingly.

A timelapse would have worked — essentially hundreds of stills like these stitched into a video sequence — though I didn’t have time to process one during the trip. Here’s an example on Reddit of an aurora timelapse from Greenland, whereby still images are stitched together in-camera to create a video.

Despite its limitations, the X5 produced colorful, bright stills of all-sky aurora. Images showed noticeable softness and noise, making them great for sharing but not for archival or print-quality work.

Verdict

Whether a 360 camera suits astrophotography depends on your goals. For scientific or high-resolution imaging, a full-frame camera with a fisheye lens still far outperforms any consumer 360 model. Observatory all-sky cameras — with large, low-noise sensors — also remain in a different league.

Where 360 cameras excel is in documenting experiences: aurora viewing, eclipses, or nights under the stars. They capture both the sky and the landscape in a single immersive frame, producing striking images even from modest displays.

So, is 4K per hemisphere enough? Not for deep-sky astrophotography — but it’s more than enough for the aurora. It’s not yet time to leave your DSLR or mirrorless camera at home, but next time you head north, consider adding a 360 camera — and don’t forget a tough tripod!

Jamie Carter travelled to Churchill with Lazy Bear Expeditions.

Check out our guide to the best 360 cameras

Jamie has been writing about photography, astronomy, astro-tourism and astrophotography for over 20 years, producing content for Forbes.com, Space.com, Live Science, Techradar, T3, BBC Wildlife, Science Focus, New Scientist, Sky & Telescope, BBC Sky At Night, South China Morning Post, The Guardian, The Telegraph and Travel+Leisure.

As the editor of When Is The Next Eclipse and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, he has a wealth of experience, expertise and enthusiasm for astrophotography, from capturing the Northern Lights, the moon and meteor showers to solar and lunar eclipses.

He also brings a great deal of knowledge on action cameras, 360 cameras, AI cameras, camera backpacks, telescopes, gimbals, tripods and all manner of photography equipment.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.