Camera mirrors are gone – are mechanical shutters next? It's all good, right?

Mirrors have been swapped for electronics, and shutters will surely be next – but are we losing our grip on the physical world?

There is a saying that the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and it seems true that every advance in camera design seems to make perfect sense. Mirrorless cameras are perhaps the single biggest example, a breakthrough that made cameras smaller and simpler and allowed a single AF system for both viewfinder and live view shooting.

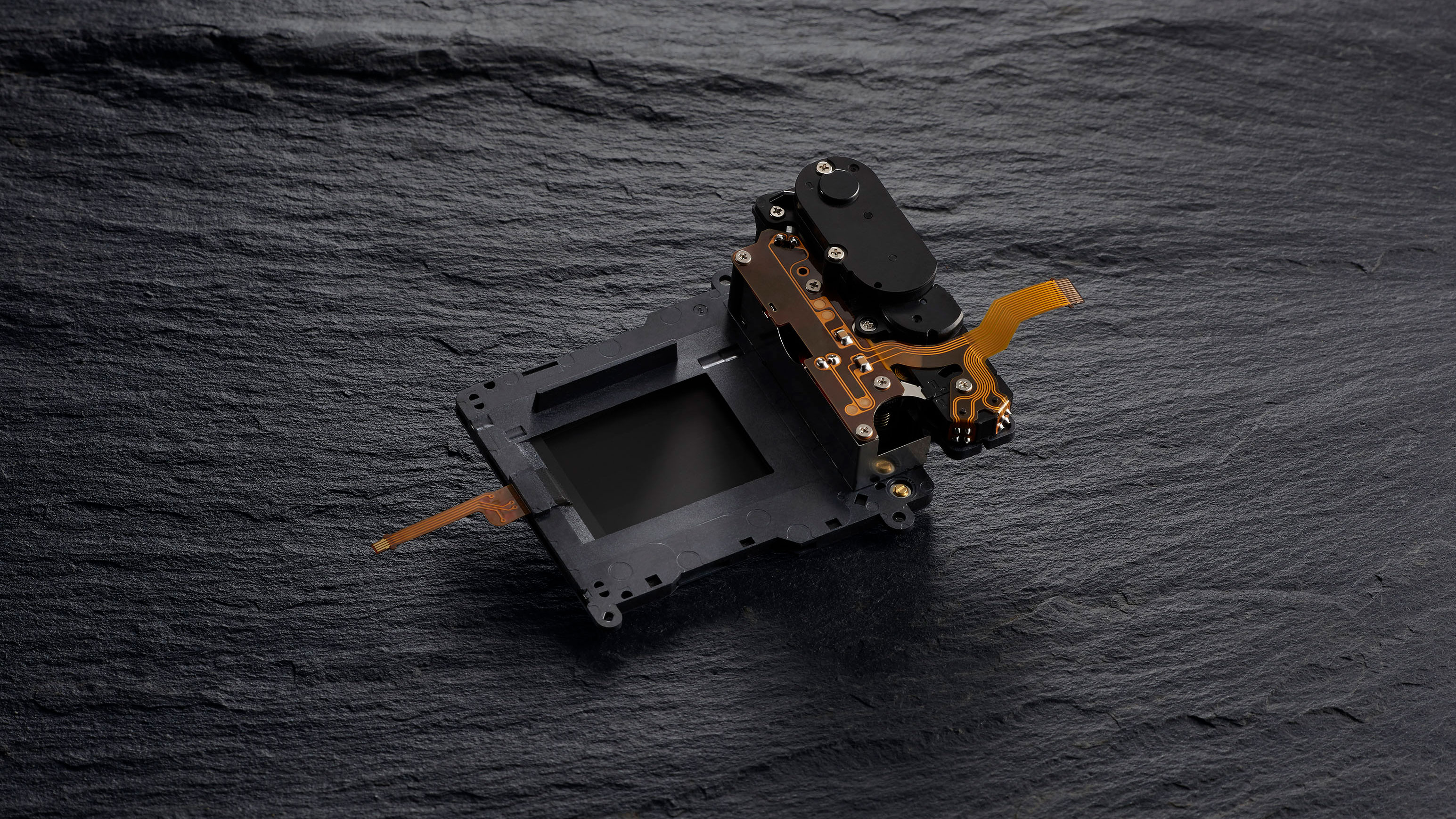

And mechanical shutters will almost certainly be next. After all, why use physical shutter blinds when you can simply ‘read’ a sensor electronically? Many cameras now offer both mechanical and electronic shutter modes, with much higher ‘shutter speeds’ with the latter. Some cameras have dropped the mechanical shutter altogether, notably the Sigma fp and fp L, and for video shooters electronic shutters are a fact of life – you can’t have a mechanical shutter crashing up and down 30, 60 or even 240 times a second.

So why haven’t electronic shutters taken over?

There is a problem with electronic shutters – and the bigger the sensor, the bigger the problem. In the ideal world, every camera would have a ‘global shutter’ – in other words, the whole area of the sensor would be read instantaneously. It’s the Holy Grail of sensor design (or a digital 3D render thereof – let’s keep with the digital theme).

There are some specialised cameras with global shutters already, but not amongst the mainstream cameras we use for photography and video. The issue is that reading the whole sensor area instantaneously requires incredibly fast readout speeds and processing capabilities. And we’re just not there yet with the cameras we use.

Instead, most cameras ‘read’ the sensor in strips, a bit like the way scanners work, so that while you may get a shutter speed of 1/32,000sec on paper, in reality, this is just the time the photosites are exposed for – and they’re not all exposed at the same time. In fact, it may take as long as 1/30sec (our estimate based on what we know of current tech) to read the whole sensor even when the shutter speed is far faster.

This causes issues for fast-moving subjects and fast camera movement – it’s the reason for the phenomenon known as ‘rolling shutter’ amongst videographers. If the subject or the camera moves too quickly for the electronic ‘scan’, verticals appear slanted, objects become distorted. It can give videos the so-called ‘jello’ effect.

Some manufacturers have got round this with very advanced (and very expensive) sensors and processing. Sony reckons it’s all but eliminated rolling shutter, or shutter ‘distortion’, with the Sony A9 II and Sony A1.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Technology moves quickly and soon, no doubt, shutter distortion will be overcome and electronic shutters will become mainstream.

So is that the end of the problem? Are mechanical shutters next in line for the scrapheap? Maybe, and maybe that’s a good thing. But maybe it isn’t.

Mechanical versus electronic: are we losing our way?

The arguments seem obvious. Of COURSE a camera without a mirror is simpler (we say)… but is it? A DSLR’s viewing system just needs a mirror, some springs and levers and a glass pentaprism. It doesn’t need battery-guzzling electronics, high-tech chip manufacture and a high-resolution miniature display panel.

And while a mechanical shutter does have a lot of moving parts where an electronic shutter has none, it does mean swapping physical mechanisms perfected for decades for 'digital' shutters that are almost but not quite there yet (agreed, for video, mechanical shutters are no good at all).

We seem to have adopted, without question, the belief that finely-tuned physical mechanisms are innately inferior to solid state electronics… and as a side-note, the past couple of years have shown us that high technology can be one of the first casualties of global disruption.

And there is a backlash. Film cameras are now more popular than they have been for decades, instant cameras with all their imperfections and unrepeatable instant prints are selling like hot cakes, and Fujifilm has forged a hugely successful business out of making cameras how they used to be made. Some of us like music on vinyl, or mechanical/automatic watches. The common factor is that they all celebrate the physical object as opposed to the electronic.

Human beings are physical creatures. We like knobs and dials, leatherette and levers. We like springs and spigots, glass and brass. Technically, modern cameras are light years ahead of those we used a generation ago, but have they lost their physical appeal along the way?

Cameras operate in a very simple way – a box with the film/sensor, a lens to focus the image and a shutter to control the length of the exposure. How have we made it so complicated, and why have we sacrificed the elegance and finesse of physical mechanisms for the soundless sterility of electronics?

Read more:

• DSLR vs mirrorless cameras

• Best DSLRs

• Best retro cameras

• Best film cameras

• Best Leica cameras

Rod is an independent photography journalist and editor, and a long-standing Digital Camera World contributor, having previously worked as DCW's Group Reviews editor. Before that he has been technique editor on N-Photo, Head of Testing for the photography division and Camera Channel editor on TechRadar, as well as contributing to many other publications. He has been writing about photography technique, photo editing and digital cameras since they first appeared, and before that began his career writing about film photography. He has used and reviewed practically every interchangeable lens camera launched in the past 20 years, from entry-level DSLRs to medium format cameras, together with lenses, tripods, gimbals, light meters, camera bags and more. Rod has his own camera gear blog at fotovolo.com but also writes about photo-editing applications and techniques at lifeafterphotoshop.com