The name behind Kodak: George Eastman

Kodak founder George Eastman was the man who brought snapshot photography to the masses

You know the brand name and you probably know some of the history behind it, but what about the people who made it happen? In this series we’re looking at the personalities who, through often courageous decisions, got us to where we are in photography today. In this profile, we meet the man who created photography’s greatest success story and one of its most recognizable brands… even today. This is the story of Kodak - and its pioneering founder George Eastman.

The challenges faced by Kodak during photography’s transition from film to digital have been well documented, but often inaccurately. Before we go back to the beginning and look at the foundations that were laid for what became film photography’s most successful brand for close to a century, it’s worth making a few points about the more recent past.

For starters, Kodak did not fail because it couldn’t adapt to digital imaging. On the contrary, the company – which had one of the best R&D operations in the world – was at the leading edge of most of the key developments in digital imaging, including creating what is now recognized as the first ‘filmless’ camera in 1975.

This was, of course, little more than a lab experiment, but it confirmed that Kodak started looking at possible alternatives to film photography for the future at pretty much the same time as Sony was working on it too.

Subsequently, Kodak would go on to pioneer the DSLR (the DCS100 in 1991, based on the Nikon F3), the first digital medium format capture back for untethered shooting (the DCS645 in 1995), and the compact digital point-and-shoot camera (the DC20 in 1996), the latter spawning a long line of models lasting into the early 2000s. However, the higher-end models were long gone, victims of the now much-diversified Kodak losing its way in imaging.

As happened in many other photo companies at the time, Kodak cut staff to stem its growing losses and, in the process, lost a lot of the senior managers and engineers who knew how to keep the company competitive in the ever-changing landscape of digital imaging. Indeed, historically, Kodak had often been the instigator of changes in photography.

There were concerted attempts to turn the business around – including a big tilt at the inkjet printer market – but overall there was a lack of any clear vision (no pun intended) and bankruptcy was declared in January 2012.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The subsequent sell-off of valuable assets, such as numerous patents, and various key business operations, like its sensor division, left Kodak a mere shell of its once glorious former self. Contrary to popular perception, however, it did survive. Today there are two separate Kodaks – Eastman Kodak Company still headquartered in the USA at Rochester, New York, and Kodak Alaris, which is based in the UK and was created as part of a strategy to extract the original company from bankruptcy.

Faced with massive claims from the UK Kodak Pension Plan, what amounted to the consumer products division, was sold to it and the new company formed. It’s Kodak Alaris that continues to make and market Kodak films, including Ektachrome, Portra, and T-Max.

Business sense

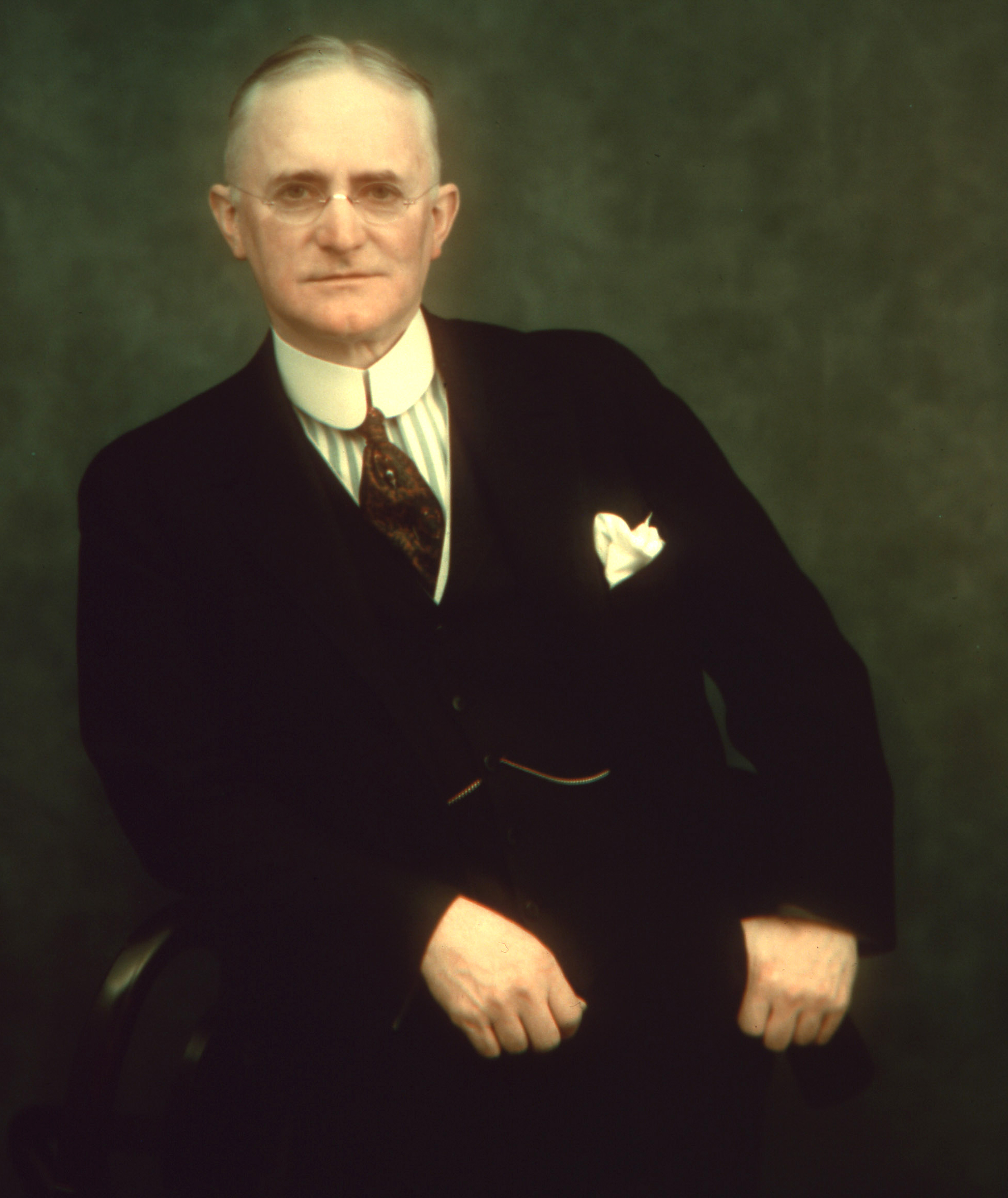

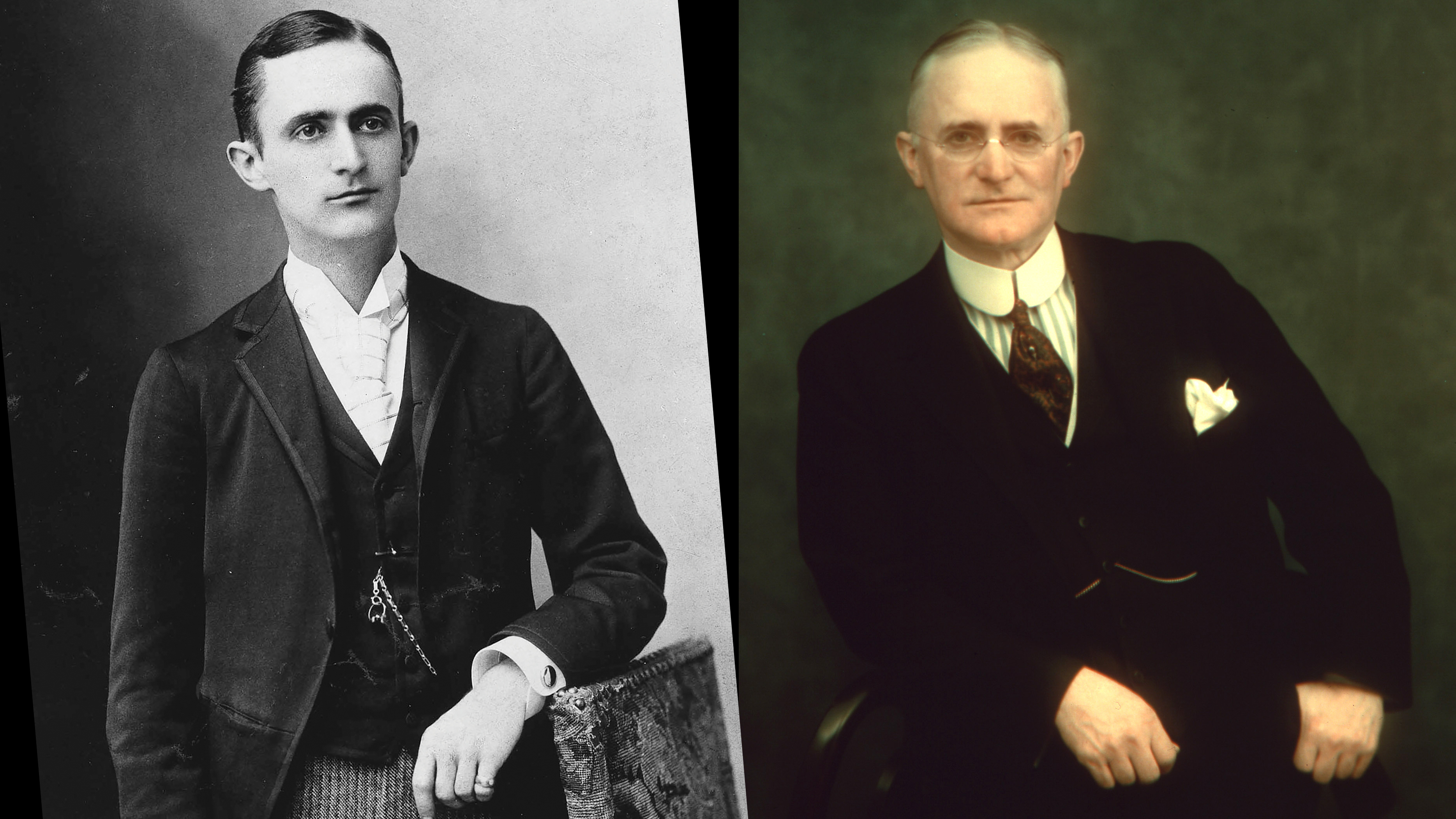

It’s interesting to speculate about what might have happened had Kodak still been run during this time by the man who founded the company in 1888, George Eastman. He was born on 12 July 1854 in Waterville, New York, on the family’s farm, although his father, George Sr, had just opened a business college in the city of Rochester around 160km away.

The college became a successful business so, in 1860, the Eastman family moved to Rochester, which prospered until the American Civil War (1861-1865) took its toll on the national economy. Additionally, George Sr died suddenly in 1862, and the family’s change in fortunes probably had something to do with fostering the young George’s entrepreneurial talents.

Clearly already aware of the value of a dollar, George Eastman left school at 14 to take on a paying job in an insurance office – where he stayed until he was 20 – before moving on to become a bookkeeper at the Rochester Savings Bank. By now he was also running the Eastman family’s finances and, with disposable income to hand, had started to develop an interest in the new medium of photography.

Like so many American industrialists of his time, George Eastman built his business around making a previously complicated and expensive process or product more accessible and affordable. In George’s case this process was photography, and it was after purchasing his first photographic kit in 1877 – which used wet plates, included a cumbersome darkroom tent and cost him what amounted to about a month’s wages – that he became convinced there had to be a better way.

The wet plates had to be coated with collodion and then sensitized with nitrates of silver just prior to exposure otherwise it quickly lost sensitivity. Eastman described the camera as being “about the size of soapbox” and its tripod as “heavy enough to support a bungalow”.

He resolved to make the whole process a lot easier and more affordable… with an eye on the commercial potential that might accompany the popularizing of photography. He began exploring the possibilities of dry plate technology, which was then brand new and still quite experimental.

Convinced the convenience would have commercial implications, George worked on his own formulation – at the sink in his mother’s kitchen – until he came up with one that worked to his satisfaction… both in terms of efficacy and economy. In fact, he was so happy with it, he decided to go into production and, in the process, invented a mechanical coating machine to ensure a more precise – and thus probably more economical – process than doing it by hand.

There was another value to this invention too, and George was quick to apply for patents for both the machine and his dry plate formulation in the USA and the UK. Over time, Kodak would become one of the most prolific US corporations in lodging patent applications and then used the rights licenses almost as a currency when there was a need to raise funds. Infringements were also rigorously contested, although Kodak was caught out itself on a number of occasions, perhaps most notably in 1976 by Polaroid – another keen collector of patents – over design elements of its instant color print film.

First steps… and a great leap

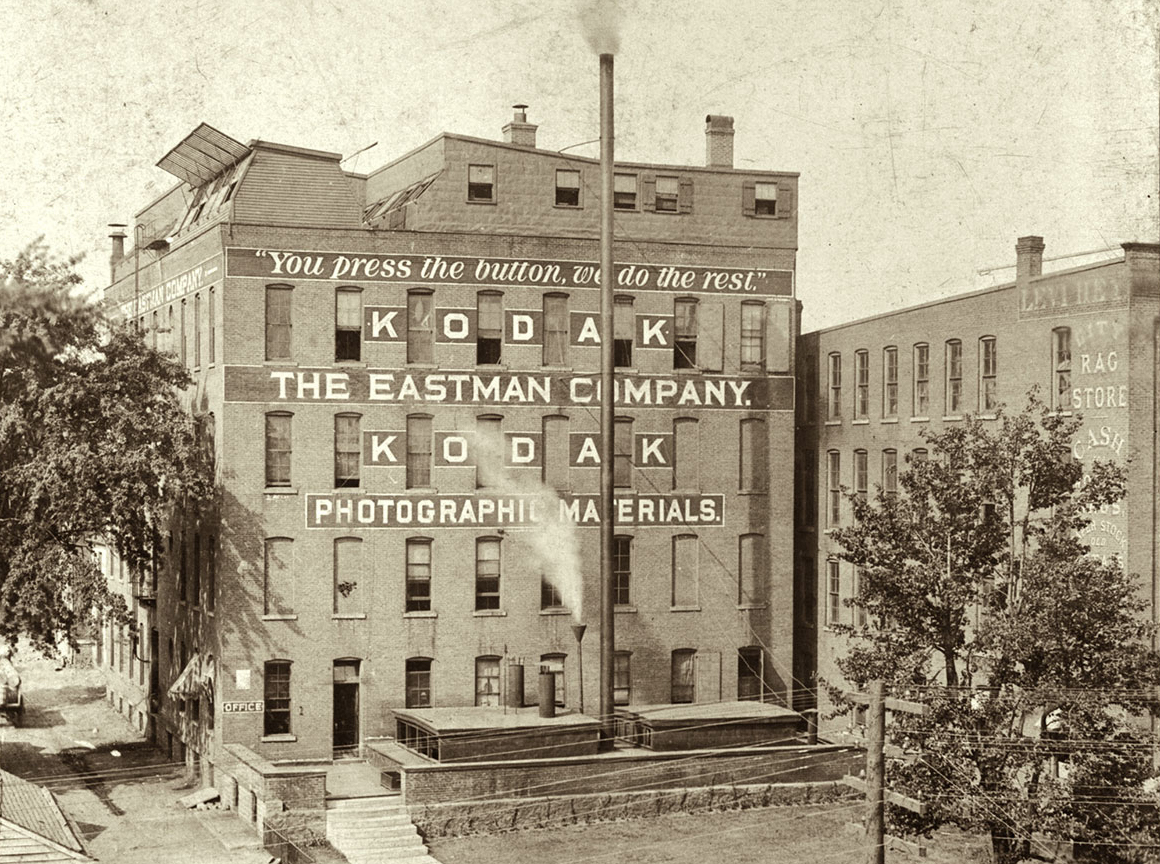

In 1880, using both his own money and that of an investor, Henry Strong, George Eastman started a business called the Eastman Dry Plate Company, operating in one room above a music shop in Rochester. His dry plates quickly gained a reputation for their quality, but already he was thinking ahead and considering ways to make photography much more attractive to amateurs… in fact, no, he wanted to reach an even wider audience; the general public.

Dry plates made things easier, but photography was still a complex and costly procedure that required some expertise and dedication. Eastman set himself the challenge of creating a system that would not only be easier, but allow for large-scale production using less expensive materials in order to make the products more affordably priced. He was about to completely redesign photography. He began experimenting with coating a light-sensitive gelatin based emulsion onto a paper backing and, after a lot of trial and error, eventually came up with a workable design.

Consequently, in 1885, the business name was changed to the Eastman Dry Plate & Film Company. At around the same time, George teamed up with a camera maker called William Walker who had already designed and built a small wooden box camera that could be handheld and, even better, lent itself to volume production. The pair then devised a holder that would accommodate Eastman’s paper negative roll film and fit into Walker’s camera.

As seems to have happened with every major development in the history of photography, the roll film camera met with some resistance despite the obvious conveniences. As far as established photographers were concerned, the paper negatives were inferior in quality to glass plates (graininess was a major issue) and their opinions were influential in what was then a very small community worldwide.

Aware of the problem, George devised a new triple-layer negative that he called ‘American Film’ and, while it solved the grain issue, it was much more complicated to develop, which limited its appeal to would-be amateur photographers. Nevertheless, this didn’t deter George from going ahead and establishing a production facility to coat long rolls of paper. He was also working on a more compact roll film camera, but he also knew he still hadn’t achieved the goal of devising a photography system that would have the appeal necessary to create a market large enough to generate the economies of scale needed for a profitable business. But he was edging closer and closer.

Out of the box

In September 1888, George Eastman registered the name ‘Kodak’, which he planned to use on his new, more compact box camera. It was an entirely invented name that came from nowhere other than his head and it was designed to be short, easily pronounced and without any previous associations. It was, he noted at the time, simply “the Kodak”.

The real genius was in the packaging and the marketing, because the first Kodak camera came preloaded with film – the triple-layer ‘American Film’ – included in the purchase price of US$25. There was sufficient film for 100 pictures and, once it was finished, the whole camera was sent back to Eastman Dry Plate & Film Company for processing and printing. It was then reloaded with new film and sent back along with the prints and the negatives. Consequently, consumers never even saw the film, let alone had to worry about the complexities of developing it.

In fact, the Kodak camera’s operation involved only three simple steps. This revolutionizing of the practice of photography led George Eastman to coin the famous advertising slogan, “Kodak Cameras. You press the button, we do the rest”.

Today this is what would be called a ‘closed loop’ system and the other genius aspect of it was that the Eastman Company had every part of it sewn up: the camera, the film and the processing – and all protected by patents.

Furthermore, backed by advertising and wider distribution – also considered by George to be key elements for a successful business – the Kodak camera was an overnight sensation and was soon selling in huge numbers to, importantly, a completely new audience.

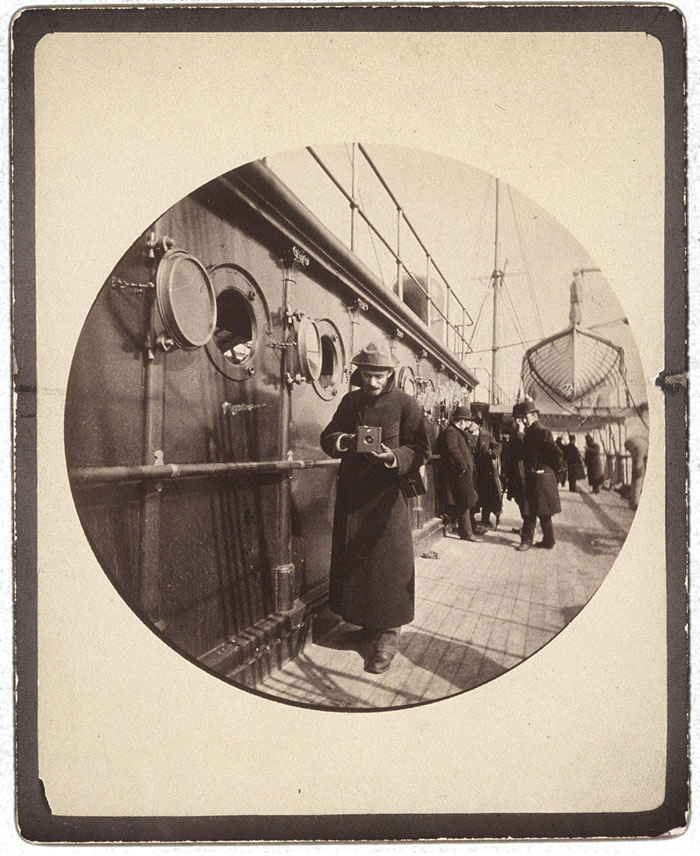

Snapshot photography was born and for a long time it would be synonymous with the name Kodak. Due to the limitations of the simple two-element lens, the earliest Kodak camera produced circular images.

Popularity equals profitability

While his camera system was receiving rave reviews from around the world, George Eastman knew that there was much more that could be improved and he was enough of a realist to know that he’d reached the end of his self-taught abilities and that he needed to hire experts. A stronger, more flexible transparent film backing material was the next challenge and, again, it had to be manufacturable in volumes that made it economically viable.

By the early 1890s, a nitrocelluloid base had been perfected along with the production techniques to make very long strips that were cut for loading into the camera. The long rolls attracted the attention of other pioneers, namely those working on the concept of ‘moving’ pictures created from multiple still frames.

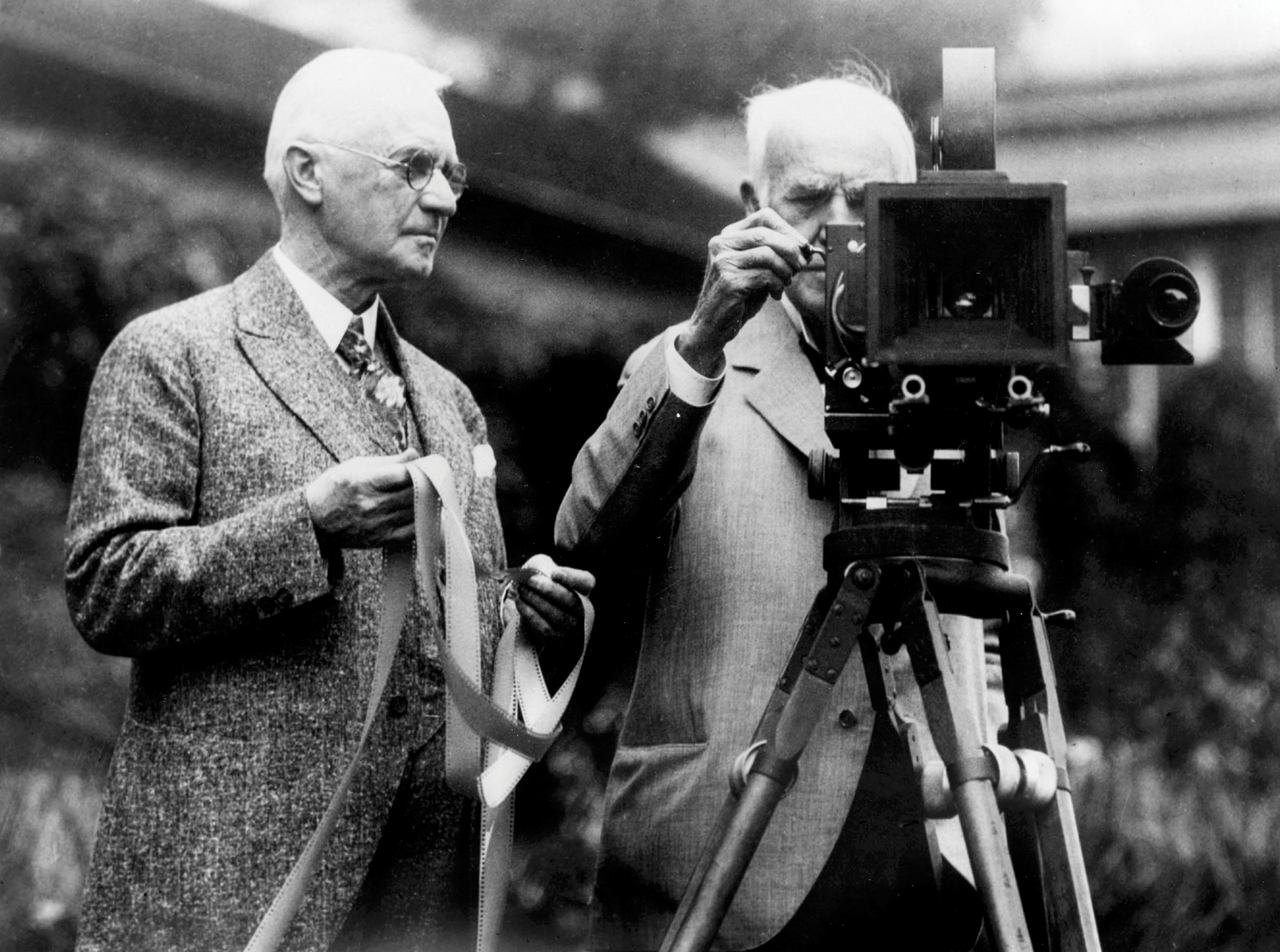

Among them was Thomas Edison – of electric light bulb fame – who started using the 70mm wide film slit in half to give a 35mm frame, and with the two lengths spliced together to create 50-foot rolls. Another revolution was in the making.

In May 1892, the company name was changed to Eastman Kodak Company and, a few years later, camera sales reached 100,000. Reports at the time suggest there was some shock and dismay at so many people now having unobtrusive cameras and photographing whatever they liked… although this would have been nothing compared to the ubiquitousness of the camera phone today.

George Eastman was determined to put as many Kodak cameras in the hands of as many people as possible, and the next big step towards this goal was an even smaller and cheaper camera, the Brownie, which was launched in 1900.

Designed by Frank Brownell – whose camera factory in Rochester had been building the earlier models for Eastman – it cost just a dollar and was so simple to use that a lot of its marketing was directed at children. By now, Eastman Kodak had developed a light-tight cartridge for easier film handling – opening up more options for processing – and the Brownie was sold with just enough film for six exposures.

In roughly only a year, close to 250,000 Brownies were sold and the company now employed 1,000 people in a purpose-built complex called Kodak Park, which was where the films and photo papers were manufactured and which also included a research laboratory. Around another 1,000 worked in Frank Brownell’s camera factory and there was another production facility at Harrow in England.

By now there were Kodak retail outlets all over the world, and the camera line had expanded into a wide range of models encompassing many budgets and skill levels. While Eastman pursued the snapshot market to achieve production volumes that would be profitable, he also recognized the importance of Kodak cameras being used by high-profile professional photographers and celebrities.

Wealth and health

Over the next couple of decades Kodak went from strength to strength with the development of home movie cameras and films (again based on the concept of keeping everything as simple as possible), steadily more involvement in the growing phenomena of cinema with new motion picture stocks, and the creation of new camera lines including many with the Autographic feature, which allowed for basic details about the image to be etched onto the negative with a stylus.

Over this time as well, Eastman began to scale back his involvement in the day-to-day running of Kodak, the company which had consumed so much of his life (although he remained treasurer, the finances always being close to his heart).

In 1930, when Kodak celebrated its 50th anniversary, he turned 76 and was increasingly suffering from ill-health, in particular a spinal disorder that was becoming more painful and restrictive. Such was his commitment to his business, Eastman had never married and his small group of friends were mainly either people he had known since childhood or were colleagues. However, he was described as being “kind and sensitive” as well as “resourceful and versatile”. This was certainly borne out in his concerns for his staff – even when the company employed close to 6,000 people – and his exceedingly generous philanthropy.

By the start of the 20th century, he was already a very wealthy man – even more so since the Eastman Kodak Company had been listed on the New York stock exchange in 1899 – but he believed in sharing these rewards with the people who had helped him achieve them. Subsequently, when shareholders were paid a dividend after a successful year, the workers also got a bonus in their pay packets.

Additionally, Eastman created a scheme of cash rewards for workers who came up with ideas that helped improve efficiencies and productivity. Beyond Kodak, he had a particular interest in music, sponsoring the creation of the Rochester Symphony Orchestra and the establishment of a school of music at the University of Rochester. He was also a passionate believer in education and contributed to many other educational institutes and to hospitals. He was quite interested in funding dental clinics – particularly for the care of children – and these were established as far afield as London and Stockholm.

It’s been estimated that, during his life time, George Eastman gave away around US$100 million. For many years he donated anonymously as ‘Mr. Smith’. Many of these legacies continue to provide benefits today.

Monuments And memories

Facing an uncertain, but most likely increasingly unpleasant future – and with no immediate family to worry about – George Eastman elected to end his own life.

Typically, he first amended his will to leave most of his remaining money to the University of Rochester and the codicil was witnessed by a small group of friends at his palatial mansion on East Avenue. On the same evening, after they had left, he went into his bedroom and shot himself in the heart. The note he left behind read, “My work is done. Why wait?”. The date was 14 March, 1932 and George Eastman was aged 77.

Although its dynamic founder was gone, Kodak would remain a dominant and defining force in photography for many decades to come. The house on East Avenue was subsequently remodeled to create the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film which opened in 1949 and is now known simply as the George Eastman Museum. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966. At Kodak Park – since renamed the Eastman Business Park – a monument was erected in his honor in 1934, and in 1979 a statue was placed in the Eastman Quadrangle at the University of Rochester.

However, undoubtedly, the most enduring legacy of George Eastman’s remarkable life’s work was the popularizing of photography, making the medium available to people who didn’t consider themselves photographers, but who nevertheless still wanted to record the important events and occasions that happened throughout their lives… the ‘Kodak Moments’ as they were coined in advertising, and then more generically to signify something special.

Using Brownies, Bantams, Hawk-Eyes, Juniors, Retinas and Instamatics, countless billions of memories were preserved for future enjoyment and reminiscing. The snapshot camera business became the biggest and most profitable in photography and survived until the arrival of the smartphone.

What might George Eastman have thought about the camera phone? Well, he would have undoubtedly applauded how it’s allowed just about everybody to take photos anywhere at any time, but he would undoubtedly be horrified that the photography industry missed the opportunity to be part of the action.

Throughout his life, he predicted – mostly with uncanny accuracy – the likely twists and turns in the evolution of photography from the wet plate to the snapshot camera, including the transition to color as far back as 1912 (Kodak’s first color film was called ‘Kodachrome’ and introduced in 1913).

In 1902, commenting on the launch of a daylight developing box that eliminated the need for a darkroom, Eastman predicted, “It shall finally come to pass that children will be taught to develop before they learn to walk, and grown-up people – instead of trying word painting – will merely hand out a photograph and language will become obsolete.” It didn’t happen quite the way he envisaged but, today, images are very much a universal language.

Read more

Best film cameras

Best film

50 best photographers ever

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.