A few weeks ago I found myself in my parents' attic, flipping through photo albums from the 1990s. The faded prints of family vacations, birthdays and everyday moments sparked an unexpected realization: these tangible images had already outlasted many digital shots I've taken in the past decade.

The previous weekend, I'd tried to locate photos from my first DSLR; shots from a 2009 road trip around Romania. After hours of searching through external hard drives, cloud accounts and forgotten folders, I found only a handful; the rest had vanished into the digital ether.

Hard drive failures, account migrations, format obsolescence, and simple neglect had erased what I thought was safe. And this wasn't an isolated incident.

Last month, I received an email from Google Photos warning that my oldest albums would be deleted unless I logged in soon. A photographer friend recently lost access to a decade of images when a cloud service shuttered its consumer division with just 30 days' notice. Another discovered that RAW files from an older camera were no longer supported by current software.

The uncomfortable truth is dawning on me: some of the photos I take today may not survive the next 15 years… or even the next 15 weeks.

Paradoxical times

We're living in a paradox. We take more photographs than any generation in history; an estimated 1.4 trillion in 2024 alone. Yet we may end up being the least visually documented era in a century.

While our grandparents' yellowing Kodak prints and even great-grandparents' sepia portraits remain intact, our terabytes of digital images balance precariously on technological systems designed for planned obsolescence rather than permanence.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Consider the fragile chain that must remain unbroken for your digital images to survive until 2040:

The file formats must remain readable. The storage medium must remain intact. The accounts housing your photos must stay active. The companies must stay in business. The passwords and authentication methods must stay accessible. The metadata connecting images to their meaning must be preserved.

Break any link in this chain, and your visual history disappears.

The problem isn't just a technical one, it's a matter of culture. Our relationship with digital images fundamentally differs from physical photographs.

The sheer volume – thousands per year, rather than dozens – makes curation overwhelming. The lack of physicality reduces their perceived value. And the platforms we use prioritize recent content, pushing older images into forgotten digital basements.

Encouraging amnesia

Major tech companies have created systems that actively contribute to digital amnesia. Cloud storage appears permanent, but often hinges on subscription models or active account use.

We think all the stuff we've uploaded online is safe, but terms of service frequently include clauses enabling providers to delete "inactive" content. Migration between services is deliberately complicated, locking our visual histories into proprietary ecosystems. Even when preservation is possible technically, financial barriers arise.

To take one trivial example, I signed up for a pet-sitting site during a six-month trip to New Zealand last year. I no longer needed the account, so recently canceled the subscription. But that meant I needed to spend an hour painstakingly downloading all my images and information, just to make sure.

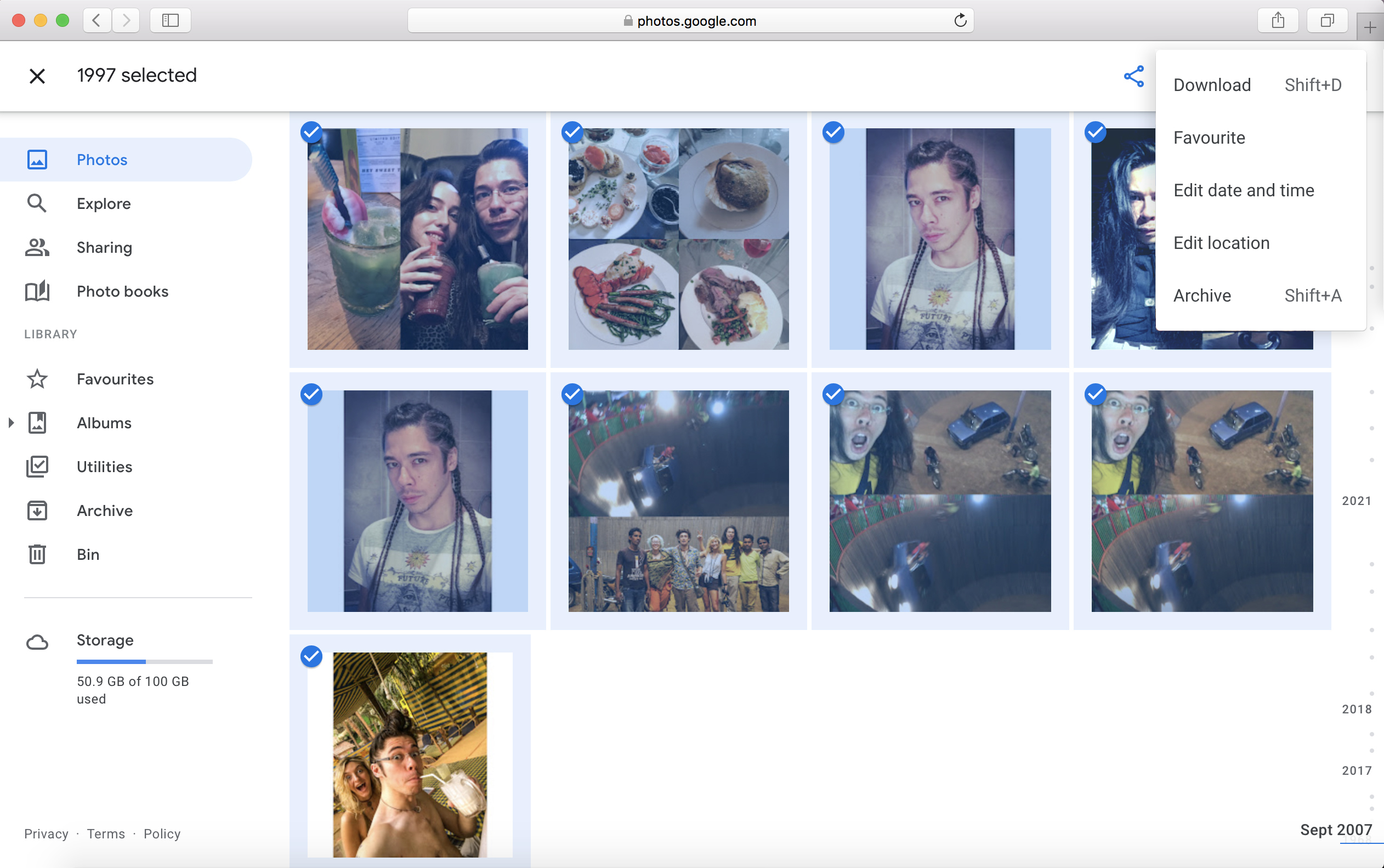

The website could, theoretically, have enabled me to do this in a single click. Yet few businesses want to make it easy for customers to leave. (Google is a notable exception, by the way, as this walkthrough explains.)

Cloud storage costs accumulate over decades. External hard drives require replacement every few years. Professional backup solutions come with professional price tags. The result? Our most precious images become hostages to recurring payments: a perpetual preservation tax.

Some photographers have recognized these dangers and returned to film or create physical prints of significant work. Others maintain elaborate backup systems; multiple drives, multiple locations, multiple cloud services. But most us don't see this as a priority… well, not unless it's too late, anyway.

Meanwhile, that box of faded prints in my parents' attic has survived decades without requiring passwords, subscriptions, compatible software or migration between storage media.

Can we say the same for the digital images we're creating today? I fear not. And by 2040, we may discover that our most precious photographs have quietly vanished, while we were busy taking new ones.

You might also like…

If this has inspired you to take a more analog archival approach, take a look at the best photo printers, the best photo printing online services and the best photo books to preserve your photos physically.

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.