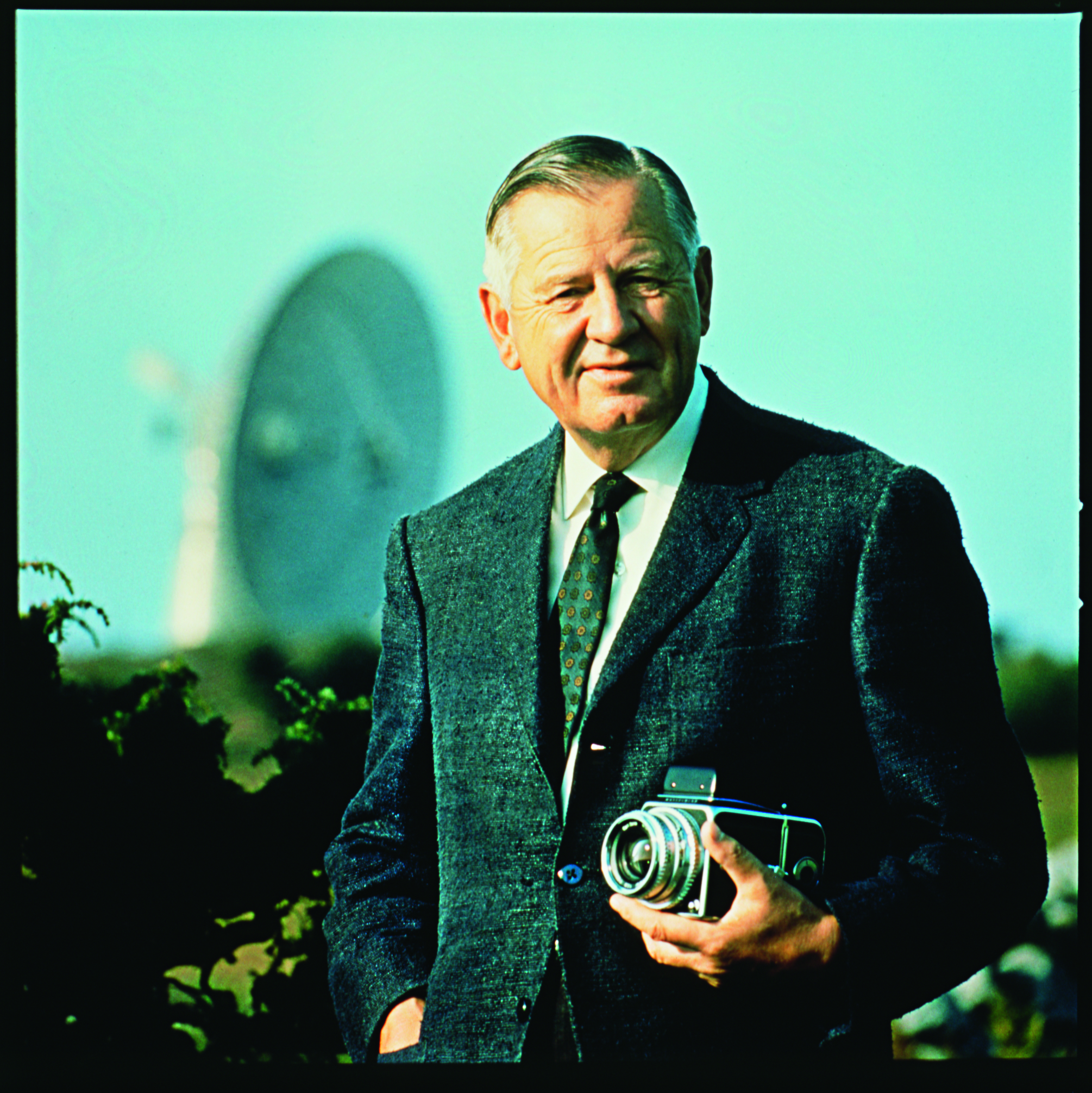

The name behind the camera: Victor Hasselblad

A look at the life of the teenager who was a passionate birdwatcher and became the creator of ‘The Swedish Dream Camera’

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fritz Victor Hasselblad was born in the Swedish port city of Gothenburg (Göteborg) on 8 March, 1906. The Hasselblad family were successful merchants who, since 1841, had mostly specialised in textiles and clothing, but in 1885, branched out into the fledgling medium of photography. In 1888, F.W. Hasselblad & Co became the exclusive Swedish distributor of Eastman Kodak products. A couple of years after Victor was born, in 1908, the family company established a new division called Hasselblads Fotografiska AB – Hasselblad Photographic Limited – which created a chain of retail outlets and photo processing facilities all over Sweden.

This article originally appeared in Australian Camera magazine, one of Digital Camera World's sister titles Down Under. Click here to find out more about Australian Camera magazine, including how you can subscribe to the print issues or buy digital editions.

Not surprisingly, the young Victor developed a keen interest in photography from an early age, along with a great enthusiasm for anything to do with nature, but in particular birds. These two hobbies would eventually come together to help change the course of camera design.

Victor was so keen on being in the field that his school studies suffered, although he excelled at biology and botany. Eventually his father, Karl Erik, an engineer by profession, decided an apprenticeship in the family business would be more beneficial than finishing school.

Article continues belowThe teenager was also sent to Dresden in Germany to learn more about the camera business. He worked for ICA-Werken – which later became Zeiss Ikon – learning much about the workings of cameras and lenses and, in the process, also becoming fluent in German. Now aged 20, Victor subsequently moved to Paris where he worked in the Kodak-Pathe shop on the Avenue de l’Opera and learned French (he also became fluent in Dutch and, of course, English).

Wherever he was in the world, he continued to pursue his twin passions for ornithology and photography.

In 1926, Victor moved to the USA and worked for Kodak at its headquarters in Rochester. While there, he came to the attention of the company’s founder, George Eastman, who invited him to dinner on quite a few occasions.

Eventually, Victor returned to Sweden to work in the family business that had now expanded to a chain of photography stores across Sweden. He purchased a Husqvarna motorcycle that he used to travel around the country – and then further afield to Denmark and the Netherlands – on his many bird-watching expeditions.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

He had brought back an 8x10.5cm format Graflex camera from the USA, but was starting to learn about its limitations in the field, especially when photographing small, fast-moving subjects. He started also shooting with Leica and Contax 35mm rangefinder cameras, which he greatly admired, but he considered the small negative size to be a restriction when it came to making large-sized prints.

In 1934, Victor married Mary Erna Ingeborg Nathorst – known as Erna – in the Seglora Church at Skansen, an open-air museum in Stockholm. He was 27, she was 19. The two remained happily married until Victor’s death in 1978, but there were no children. There were, however, plenty of dogs, including one called Leica. Erna died in 1983, aged 68.

In 1935, Victor had a book published called Flyttfågelstråk – The Flight Of Migratory Birds – which he both wrote and photographed. It was a reasonable success, but it came at a cost as the long absences from the family business had further tested an already strained relationship with his father. Eventually Karl Erik ran out of patience and, in 1937, dismissed his son. The two would never speak again.

No doubt to prove a point, but also because he badly needed an income, Victor decided to start his own company – Victor Hasselblad AB – and opened a shop called Victor Foto – located on one of Gothenburg’s main city squares – which combined a photography business with a camera repair workshop. Ironically, Victor Foto was just around the corner from the old family business’s main office.

Taking flight

While spending long hours in hides watching birds, Victor had begun to dream up his ideal camera. It needed to be a reflex design. It had to allow for quick adjustments. It had to have interchangeable lenses. It needed to be smaller and lighter than the Graflex, but have a bigger negative size than 35mm. This was to allow for much greater enlargements while preserving very fine details such as feathers.

Initially though, Victor wasn’t entirely certain about the SLR configuration. He wrote at the time, “It is true that with such a design, one has the possibility of controlling the settings right up to the moment of exposure, though that possibility is often an illusion when photographing quarry that is running towards you because if one can see the animal clearly in the mirror, it still has time to move an appreciable amount during those moments from the time when the mirror is raised to the point where the focal plane shutter is released”.

Through his skilled work at his camera repair shop, Victor became known for his technical prowess and so, after the Second World War started, he was approached by the Royal Swedish Air Force in early 1940 to design a handheld aerial camera. The Swedes had captured an intact German-made aerial camera from a downed Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft and brought it to Victor with the expectation he would be able to replicate it.

He recalled, “I received an inquiry – can you make a camera like this? And they showed me the captured German camera. I inspected it closely, and saw that it wasn’t anything very special. So I replied truthfully, ‘No, I cannot make one like that, but I can make one better’.”

The Air Force promptly ordered a prototype. If Victor Hasselblad realised the enormity of the challenge now facing him, he didn’t let it daunt him and quickly set about the design work, sourcing the necessary tooling and setting up the production facilities (under a separate company called Ross AB).

This first workshop was in a spare shed on the premises of the garage where Victor had his car serviced. Nearby was a junkyard where he began regularly raiding for raw materials that were already in short supply due to the war. In the evenings, with the help of his car mechanic, Gustaf Tranefors and Tranefors’s brother Åke, Victor began reverse engineering the German camera and improving both the design and the construction.

The result was the very first Hasselblad camera, called the HK-7, although it was actually badged as ‘ROSS Aktiebolag’. However, the prototype was rushed and it consequently failed on its first demonstration, but Victor was undeterred and quickly came up with a revised design, which did work.

The Swedish Air Force ordered enough for production to commence so, within a few months, the fledgling company had a proper factory with 20 workers. The HK-7 was a handheld, aluminium-bodied camera capable of recording 7x9cm images on 80mm film and had interchangeble lenses.

Ross AB built everything, including the leaf shutter assemblies, but the interchangeable lenses were sourced from Zeiss, Schneider and Meyer-Görlitz.

A total of 240 HK-7s were built, and some elements of the first civilian Hasselblad camera can be seen in the design, including the adoption of a leaf shutter. Also evident right from the start was Hasselblad’s emphasis on mechanical precision, reliability and durability. As an aside, Åke Tranefors went on to work for Hasselblad for the next 40 years.

Victor’s next aerial camera, the SKa4, represented another evolutionary step towards the first Hasselblad consumer camera – Victor’s ideal camera – as it used a square format (albeit a much larger image size of 12x12cm) and now also had interchangeable film magazines. These magazines housed specially-made, double-perforated film in 13cm wide rolls.

Unlike the handheld HK-7, the SKa4 was designed to be mounted in the belly of an aircraft – pointing directly downwards – to take high-resolution reconnaissance images automatically at intervals with an overlap to enable stereoscopic photo interpretation. It’s estimated that 70 Ska4 cameras were build.

In 1943, Ross also began making a camera specifically for the Swedish Army, called the MK80, which was 7x12cm in format and could be fitted with a periscope attachment for photographing from behind walls or other structures.

Back in the field

In May 1942, Victor’s father died and the way was opened for him to not only return to the family business, but to acquire it outright. Over at Ross, he was already instructing his employees to start thinking beyond the war, and so the groundwork was laid for the creation of a non-military camera based loosely on the HK-7. At that stage, it was simply called the “civilian camera”.

By 1945, a number of rough prototypes had been built, but Victor realised that he was going to need something a bit more refined for the civilian market. As it happened, his company was also manufacturing some precision components for aircraft-maker Saab, and this brought Victor into contact with the great Swedish designer Sixten Sason whom he subsequently commissioned to style his camera. Sason went on to design Saab’s first car, the 92, and the streamlined Elektrolux (later called Electrolux) Z 70 vacuum cleaner. Despite being very different products, all three share quite similar design elements.

Hasselblad’s good relationship with Kodak enabled him to convince the Americans to design and build the interchangeable lenses for his new camera. Four models were initially ordered – an Ektar 80mm f/2.8 standard lens, an Ektar 55mm f/6.3 wide-angle, an Ektar 135mm f/3.5 short telephoto and an Ektar 254mm f/5.6 long telephoto.

All he now needed was a name and, after considering both Ross and Victor, one of his friends at Kodak asked, “Why not call it Hasselblad?”

Failures... and success

No doubt with a shrewd eye on the huge potential of the American market, the launch of Victor Hasselblad’s grand design took place at the Athletic Club in New York on 6 October, 1948. The New York Herald Tribune newspaper subsequently reported on the event under the headline, “European Maker Beats U.S. Camera Firms Again”.

The Hasselblad 1600F – although this model designation wasn’t actually adopted until later – was notable for its fully modular design that allowed for the interchanging of not just lenses, but also viewfinders and film magazines. The horizontal box-form SLR design promoted comfortable handling, fast operations (such as film winding) and also comparatively compact dimensions given the frame size of two-and-a-quarter-square inches or 6x6cm. Appropriately, it earned the tag of ‘The Swedish Dream Camera’.

However, while the essential design of the 1600F may have been inspired, technically the camera was more of a nightmare. Most problematic was its focal plane (mechanical) shutter which, theoretically, had a top speed of 1/1600 second, but in reality was rather slower… or didn’t work at all, such was the fragility derived from the need to make the curtains as lightweight as possible and the demand on the mechanism in order to deliver the necessary rate of acceleration.

When deliveries began in early 1949, most of the early cameras failed and Hasselblad sent an engineer to the USA specifically to deal with the problem. Nevertheless, interest in the new camera continued to grow and a major coup was its early adoption by Ansel Adams who described it as “revolutionary in a number of important ways”. Adams went on to have a long relationship with Victor Hasselblad and his cameras, and was frequently involved in the field testing of new products.

An updated ‘Series 2’ 1600F model was introduced in 1950. It improved overall reliability, but the fragile shutter remained problematic. In 1953, the new 1000F was released with a more achievable top shutter speed of 1/1000 second and significantly better reliability. With the arrival of the 1000F, the previous model was then christened the 1600F.

By now, Hasselblad also switched to Zeiss for its lenses and these included the 38mm f/4.5 Biogon ultra-wide, which was mated to a dedicated non-reflex body to create the SWA (Super Wide Angle) camera. The company took both these new models to the 1954 Photokina in Cologne where they created a great deal of interest. Hasselblad, maker of fine medium format cameras, had arrived.

New leaf

While the 1000F was a reasonable success, Victor eventually decided to abandon the focal plane shutter altogether and adopt in-lens leaf shutters which, although they had a slower top speed of 1/500 second, allowed flash sync at all speeds. In 1957, the 500C was launched (the ‘C’ stands for Compur, the shutter’s manufacturer) and thus began a line of film cameras that continued until 2013. What’s more, the last-of-the-line 503CW was fundamentally the same camera as the original 500C – a fully mechanical 6x6cm SLR with interchangeable leaf-shutter lenses, viewfinders and film magazines.

There were, of course, a lot of refinements along the way, although the 500C stayed unchanged until 1970. In that period Hasselblad also devised a motorised version, the 500EL, which was launched in 1965, while the SWA became the SWC in 1959 (the key upgrade was the linking of the film advance and shutter recocking functions).

Hasselblad’s long association with NASA began in 1962 with the 500C that astronaut Walter M. Schirra used aboard the Mercury space craft Sigma 7 when it orbited the globe six times on 3 October. Schirra owned his own 500C and showed it to NASA’s engineers who then bought one from a camera store and modified it for operation in a weightless environment.

The subsequent Gemini missions also used the 500C, but it was the motorised 500EL that interested NASA the most and it was two special versions of this camera – called the Hasselblad Electric Data Camera (HEDC) and the Hasselblad Electric Camera (HEC) – that were aboard Apollo 11 to record the historic landing of the first men on the Moon. Victor and Erna were present at the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida on 16 July, 1969 to watch the launch of the Saturn V rocket carrying Apollo 11, its crew and three Hasselblads – one silver-painted HEDC that would be used on the Moon, and two black HECs for photography from the command module and the lunar lander.

When Victor Hasselblad was dreaming up his perfect camera for bird photography, it’s very unlikely he had any idea of the heights to which they would eventually soar.

Apart from being specially built for the application using ‘dry’ lubricants and materials that didn’t shed particles, the Hasselblad space cameras were fitted with a bulk 70mm film back (for up to 200 frames) and a simple wire-type sports finder. They also had a special 60mm f/5.6 Biogon lens. To save weight, only the film magazines came back to earth, so 12 very valuable Hasselblads are still up there (although there may be one less as it now looks like the Apollo 17 crew may have brought two cameras back).

From the Gemini program onward, Hasselblad took over the modification of NASA’s space cameras using a dedicated group of engineers based in Gothenburg.

Celebrity status

In 1970, Hasselblad introduced the model that became the backbone of so many professional camera systems over the next three decades. The 500C/M introduced a number of fairly minor revisions, but the most important upgrade was that the focusing screens were now interchangeable by the user as well. This feature was also simultaneously made available in the motor-driven 500EL/M.

By now Hasselblad was a hugely successful company that had diversified into a number of other areas, including operating a paper mill to make packaging products. In 1965, the original family company was sold to Kodak and, after the paper mill was sold, Victor Hasselblad became one of the richest men in Sweden and also something of a national celebrity. The story is told about a customs officer who looked at his passport, then looks up at its owner and says, “You have the same name as the famous camera”. To which Victor is said to have replied, “Yes, I am the camera”.

He was 60, and now devoted all his energies to his camera company. However, he continued to actively pursue his passion for bird photography and a number of major exhibitions of this work were staged during the 1970s. At one of these – in Oslo in 1975 – all the exhibition prints were sold on the first day and Victor donated the entire proceeds to the World Wildlife Fund.

In 1976 he sold his own company, Victor Hasselblad AB, to a Swedish investment firm. The last camera that Victor was directly involved with saw a return to a focal plane shutter, although the 2000FC could also be used with the ‘C’ series leaf shutter lenses as well. It was launched, along with five ‘F’ lenses without built-in shutters in 1977, and the sole concession to modern camera design was the electronically-controlled titanium shutter that could, finally, achieve a top speed of 1/2000 second… something that had been Victor’s goal right from the very start.

Again, the 2000FC was a fully manual camera with TTL metering via the CdS-based Meter Prism Finder, an additional purchase. An accessory autowinder wouldn’t become available until 1984 with the 2000FCW model. In comparison, the Rolleiflex SLX, launched in 1976, had a motorised film transport and TTL metering – using dual SPDs – with the option of shutter-priority auto exposure control.

Hasselblad’s conservative approach to adopting new technologies was rooted in Victor’s obsession with reliability – he never wanted to repeat the 1600F experience – and so it was well over two decades after his death that the company finally created

a new from-the-ground-up camera system – the 6x4.5cm format autofocus H1 was launched

in 2002.

Rare bird

With more time on their hands, in early 1978 Victor and Erna travelled to the Galápagos Islands, a place that he’d wanted to visit for a long time… not for the famous marine iguanas, but a rare bird, the Lava Gull. It was while on this trip that he exhibited the first symptoms of an undisclosed illness that subsequently ended his life on 5 August, 1978.

He was aged 72 and willed that his vast fortune be used to establish the Erna And Victor Hasselblad Foundation which, today, operates as the Hasselblad Foundation in Gothenburg to promote many aspects of education in both photography and the natural sciences.

While the digital imaging revolution began with high-end capture backs designed to fit medium format SLRs, the camera makers themselves mostly all struggled with the transition, and there were quite a few casualties. Bronica, Contax and Rollei disappeared altogether, while both Pentax and Fujifilm stopped making medium format film cameras.

Obviously Fujifilm has since returned to this market with its GFX mirrorless cameras, and Pentax revived its system with a digital camera body in 2010. The other long-term survivors have been Mamiya (now owned by Phase One) and Hasselblad, which now has Chinese drone-maker DJI as its majority shareholder.

However, Hasselblad is still making cameras in Gothenburg and today’s H6D digital camera system can trace its roots – at least in terms of its basic modular configuration – all the way back to the original 1600F. While the future is undoubtedly mirrorless cameras, such as the X1D II and the 907X, their concept of compactness, combined with fast operation and the promise of very high quality results is exactly what Victor Hasselblad originally dreamed up back in his bird-watching hide.

Related articles:

Nikon, Leica & Hasselblad: the cameras that have been to space

Hasselblad 907X 50C review

Hasselblad X1D II 50C review

Best medium format cameras

Best Hasselblad lenses

Australian Camera is the bi-monthly magazine for creative photographers, whatever their format or medium. Published since the 1970s, it's informative and entertaining content is compiled by experts in the field of digital and film photography ensuring its readers are kept up to speed with all the latest on the rapidly changing film/digital products, news and technologies. Whether its digital or film or digital and film Australian Camera magazine's primary focus is to help its readers choose and use the tools they need to create memorable images, and to enhance the skills that will make them better photographers. The magazine is edited by Paul Burrows, who has worked on the magazine since 1982.