I tried cheap cameras from Canon, Sony and Nikon on one of the most difficult subjects – this is the camera that stood out

Cheap cameras are getting far better at challenging genres like wildlife photography

Budget cameras may be great starting points, but they are notoriously poor for some of the toughest subjects to photograph – like wildlife and sports.

However, with the advancement in subject-detection autofocus, I started to wonder if, perhaps, today’s cheap cameras are starting to become more capable in capturing distant, fast subjects – or at least, less terrible at it.

To test this theory, I borrowed three under $1,000 / £1,000 / AU$1,500 cameras from Canon, Sony and Nikon to see whether today’s budget bodies are up to the task of wildlife photography.

For the comparison, I borrowed the Canon EOS R10, the Sony A6400, and the Nikon Z50 II. (There are some other budget cameras with wildlife-friendly features, but a person can only carry around so many at once.)

None of those cameras are the cheapest in their brand’s lineup: Canon has the R100, Nikon the Z30 and Sony the A6100. But there’s often a big step from the most affordable camera to the next camera up in the lineup.

The R100, for example, can only shoot at 3.5 fps when using continuous autofocus (a rate that reminds me of my first cheap DSLR years ago). The R10, on the other hand, can shoot up to 15fps with the mechanical shutter and up to 23fps with the electronic shutter. But, all three of these cameras are still relatively affordable.

One of the aspects that makes wildlife photography difficult on a budget is finding a telephoto lens at a reasonable price point. I paired each camera with the recommended telephoto from DCW’s guides to the best lenses for the Canon EOS R10, the best lenses for the Sony A6400, and the best lenses for the Nikon Z50 II.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

That left me with the Canon RF 100-400mm f/5.6-8 IS USM, the Sony E 70-350mm f/4.5-6.3 G OSS and the Nikon Z DX 50-250mm f/4.5-6.3 VR.

Admittedly, the lens selection had a far wider price range than the cameras, starting at a few hundred bucks but going all the way to around $1,200 / £830. But telephoto lenses are among some of the priciest lenses, making them one of the hardest lenses to find on a budget.

The faster something moves and the farther away it is, the more difficult it is to photograph – which is why I consider wildlife photography among the tougher genres to tackle.

Armed with three budget mirrorless cameras and lenses, I set out on some wildlife hikes and sat by my birdfeeder to see just how well cheap cameras can tackle the tough genre of wildlife photography.

Sony A6400

The smallest of the three budget cameras that I tried, the Sony A6400 is both budget- and travel-friendly. The rangefinder design with the viewfinder on the left means the camera maintains a compact size without sacrificing the viewfinder entirely.

The small design does mean that the grip isn’t as large as the likes of the Canon EOS R10 or the Nikon Z50 II – I didn’t think the grip was quite as comfortable, particularly for using a heavy telephoto.

Sony has long been known for autofocus, however, and even the affordable A6400 doesn’t disappoint. The fast autofocus mixed with 11fps bursts is certainly respectable for a camera body that doesn’t breach four figures.

The A6400 also has Pre AF, which will save a few images before the shutter is fully pressed, increasing the odds of getting an action shot.

My biggest complaint on the A6400, however, was that I needed to be far closer for the animal eye AF to kick in, where the Nikon Z50 II and Canon R100 seemed to lock in even on more distant subjects. There’s a simple explanation for this: the A6400 was introduced in 2019, and it received animal eye AF as a firmware update a few months later.

But animal eye AF has come a long way in the last six years, and this is where the A6400 starts to show its age. The AF on the newer Sony A6700 has improved with AI and is listed as one of its best features, but the A6700 didn’t meet my under $1,000 definition of a “cheap camera.”

I had to manually move the focus point to lock on to most birds – a process that’s slightly more annoying because the A6400 doesn’t have a joystick to move the focus point, which is pretty common among budget cameras. The menu controls can be customized to control the focus point, or you can do it by tapping the screen.

But while the animal detection wasn’t as advanced, the Sony 70-350mm f/4.5-6.3 G OSS was my favorite lens of the bunch – albeit the most expensive one that I tried. The lens felt sharper than a lot of crop sensor telephotos, plus it’s equipped with stabilization and weather-sealing.

While the animal eye AF felt a bit outdated, the availability of that higher-end lens gave the resulting images an edge in sharpness.

Nikon Z50 II

My first serious camera was a budget Nikon DSLR, so I was eager to try out Nikon’s fairly new Z50 II. Compared to the A6400, the Z50 II is larger – but the increase in size also gives the Z50 II a better grip.

The Z50 II has a respectable 11fps burst speed. It can shoot at faster speeds, but those higher speeds are limited to JPEG only and do not support RAW.

Another key feature for wildlife photography is Pre Capture. Activating this setting starts recording photos when the shutter button is only half-pressed, helping avoid missing the action due to a slow trigger finger.

One of the features that piqued my interest on the Z50 II is the fact that it can focus in low light down to -9 EV. In comparison, the specs list -4 EV for the R100 and -2 EV for the A6400. I didn’t go out looking for owls to photograph in the middle of the night, but the camera didn’t have any issues focusing in deep forests on a cloudy day either.

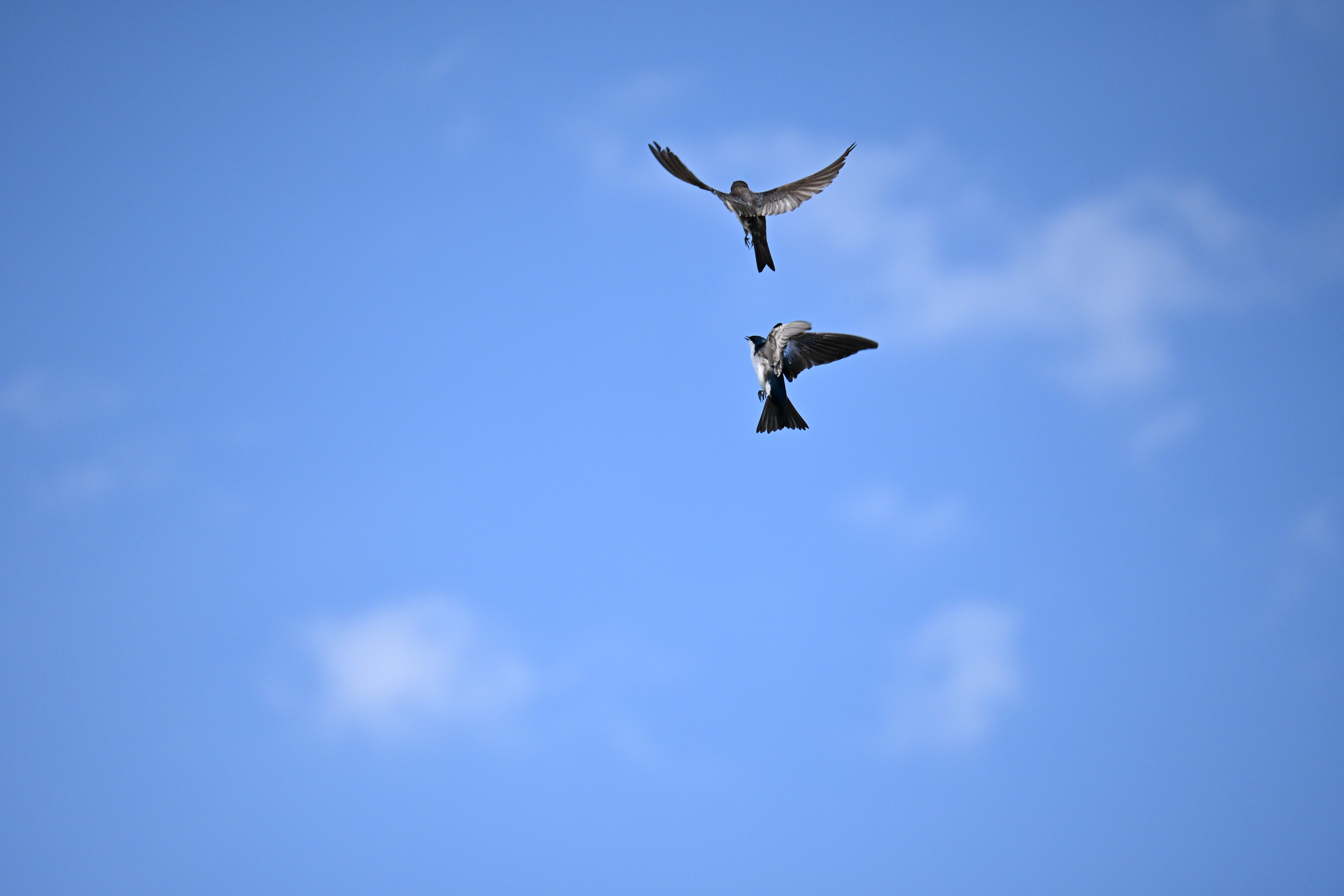

Animal eye detection on the Z50 II works quite well, even on more distant subjects. In fact, I was incredibly surprised when it picked up two tree sparrows swooping at each other – a spur-of-the-moment shot that I hadn’t anticipated and was literally a “spray and pray” situation.

The animal eye AF makes it far easier to learn wildlife photography than my first cheap camera. My only complaint about it is minor: there’s a separate mode for birds and a different one for pets, so you may need to switch between them or use the auto subject detection if both birds and mammals may wander in front of your lens.

My biggest disappointment using the Nikon Z50 II for wildlife I knew going into the test: the 50-250mm lens is shorter than the best APS-C telephotos available on the Sony E and Canon RF Mount.

I rarely feel like I have enough zoom when shooting wildlife. The Nikon 50-250mm is pleasantly compact and easy to hike with, but I did prefer the 400mm reach on the Canon RF lens. The Z50 II is compatible with Nikon’s high-end full-frame telephoto lenses for more reach, but these are pricier optics.

Thankfully, the 50-250mm is cheaper and brighter than Canon’s RF 100-400mm f/5.6-8 IS USM – the Nikon duo is more than $300 less than the Canon body and lens combo that I tried. I thought the Z50 II and R10 had similar speed and autofocus performance, but I preferred Canon’s longer lens.

Canon EOS R10

Armed with the RF 100-400mm f/5.6-8 lens, the Canon EOS R10 is quite the performer for wildlife, considering the camera and lens together retail for just over $1,600.

I’ve used sharper and brighter lenses before, but the R10 with the 100-400mm was more than capable of capturing Instagram-worthy wildlife photos, considering the price point and that long 400mm range.

The R10’s animal eye AF worked well, even with distant subjects. I was impressed at how well the R10 could often pick a bird from a mess of branches. Canon’s high-end models are a bit better at finding a bird in a busy mess of foliage, but the R10 still captured an impressive hit rate considering its price point.

The other reason that I loved using the R10 for birding is that the camera has an autofocus joystick – something that’s not common among budget cameras.

While the animal eye AF can pick up birds quite well, the joystick makes it easier to pick between multiple subjects or use smaller focusing areas for even faster performance. That, mixed with a decent-sized grip, makes the R10 feel great in my hands.

Compared to the Z50 II and A6400, however, the R10 isn’t weather-sealed, so it shouldn’t be taken out in the rain without a cover. The weather seals on the Z50 II and A6400 aren’t as tough as high-end models, but the R10 lacks them entirely.

The other thing that annoyed me about the R10, which may seem minor, is that the mechanical shutter is quite loud. Canon’s high-end cameras don’t sound quite this clunky.

Thankfully, there is a solution built right into the camera – a silent shutter mode. This uses an electronic shutter, which can introduce some distortion like banding in some scenarios, but it’s nice to have when photographing wildlife that may be scared away by the noise.

Downsides to using cheap cameras for wildlife photography

Cheap cameras have come a long way over the last five years. The budget category may not have as many features or quite as nice images, but it’s now not only possible to take wildlife photos with cheap cameras – it's also far easier than it was ten years ago, thanks to advancements in animal eye AF.

That’s not to say that there aren’t still downsides, however. None of the three budget mirrorless cameras that I tried offers in-body image stabilization, which can be a huge help for avoiding blur from camera shake – particularly with beginners using telephoto lenses.

In addition, these three cameras all max out at a shutter speed of 1/4000 sec. High-end cameras can go much faster for really freezing the movement of fast wildlife, such as birds. Upper-tier cameras will also offer faster bursts for getting the timing just right.

The list of differences between a cheap camera and a mid to high-end model goes much further, of course – including things like resolution, burst speeds, autofocus performance and durability all come into play.

Half the equation for wildlife is the lens – and longer, telephoto lenses tend to be pricey. Budget options aren’t nonexistent, however, but high-end lenses tend to be brighter, longer and weather-sealed.

Which camera won out?

The Canon EOS R10, Sony A6400 and Nikon Z50 II are all surprisingly capable cameras, even when it comes to challenging genres like wildlife. Animal detection autofocus is one of the biggest assets to new photographers, however, and the R10 and Z50 II won out here, with the A6400 being a bit behind on autofocus smarts.

Between the R10 and the Z50 II it’s a matter of priorities. The R10 has access to a $650 lens that still reaches out to an impressive 400mm, performance is impressive and the camera is comfortable to use thanks to that joystick and comfortable grip.

But the Nikon Z50 II is more affordable paired with a 50-250mm lens, and it also has some weather-sealing for venturing out to photograph wildlife in light rain.

Mirrorless cameras aren’t meant to be one-trick ponies, though, and the right choice may depend on what other genres you want to shoot.

The Nikon Z50 II has excellent low-light autofocus for the price. Pair a pancake lens with the A6400, and you can easily go from wildlife to travel-friendly with its small body. And the R10’s autofocus should also translate well to other quick subjects, plus the grip and joystick make for excellent ergonomics.

Overall, my favorite images from the cheap camera wildlife challenge came from the R10, in part because of that longer budget lens. But I also wouldn't hesitate to buy the Z50 II, especially considering it's the cheapest combo I tested. Because of the A6400's age, I'd probably save up a little longer for the A6700 for wildlife on the Sony system.

I know this for certain: I wish I had features like animal eye detection when I bought my first cheap DSLR. Budget cameras have their limitations, but the list is far shorter than the cheap interchangeable lens cameras of ten years ago.

You may also like…

Browse the best cheap cameras or the best cameras for wildlife photography.

With more than a decade of experience writing about cameras and technology, Hillary K. Grigonis leads the US coverage for Digital Camera World. Her work has appeared in Business Insider, Digital Trends, Pocket-lint, Rangefinder, The Phoblographer, and more. Her wedding and portrait photography favors a journalistic style. She’s a former Nikon shooter and a current Fujifilm user, but has tested a wide range of cameras and lenses across multiple brands. Hillary is also a licensed drone pilot.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.