Early Verdict

The Olympus OM-1 was one of the most important cameras in 35mm SLR history. The OM-1 was the start of a dynasty of OM film cameras, which were the first SLRs for many amateur photographers in the 1970s and 80s. Launched as the M-1 at the 1972 Photokina, Yoshihisa Maitani’s brilliant design for a more compact 35mm SLR was the start of big things for Olympus… and 35mm SLR design in general.

Why you can trust Digital Camera World

Taking a sober look at the history of photography, there are really only a small number of cameras that can be considered truly revolutionary – the original Kodak box camera obviously and the first Leica 35mm camera. Later, the Contax S, the Nikon F, Leica again with the M3 and the first Hasselblad 6 x 6cm SLR. And undoubtedly also on this list is the Olympus OM-1. This is the camera that made Olympus into one of the ‘big five’ Japanese camera brands during the 1970s, ‘80s and early ‘90s. It spawned a very successful line of higher-end 35mm SLRs – the OM-2, OM-3 and OM-4 with variations such as the titanium bodied ‘Ti’ models. And, from the original OM-1 and OM-2, Olympus built a range of consumer-level SLRs – OM-10, OM-20, OM-30 and OM-40.

Now that the Olympus brand is no more as far as future cameras and lenses are concerned, it’s very fitting that the last camera to wear the marque – everything will be OM System from now on – also adopts the iconic model number. In terms of what the original OM-1 did for the Olympus brand, the digital-era OM-1 has a lot to live up to, but there’s clearly some of that original DNA in the new camera’s concept and execution, and the sheer brilliance of Yoshihisa Maitani’s design continues to be recognized 50 years later.

This camera first appeared badged as the M-1 – at the 1972 Photokina in Cologne – and roughly 52,000 units were produced before Olympus agreed to Leica’s request to change the model name to avoid any confusion with its M1 35mm rangefinder model (in reality, highly unlikely). To avoid treading on European toes, a lot of M-1s were then sold into the Japanese and South-East Asian markets. From February 1973, the M-1 became the OM-1 and began turning the 35mm SLR world upside down anyway. From then on, a lot of camera designers began to think smaller, including at Pentax, with the equally compact M series that was launched in 1976.

Olympus OM-1 specifications

Camera type: 35mm film SLR

Lens mount: Olympus OM

Exposure control: Manual

Shutter speeds: Mechanical 1/1000 ec to 1 second, plus bulb

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Exposure metering: Center-weighted

Battery: One 1.35V button-type battery (625 type)

Dimensions: 136 x 83 x 50mm (body only)

Weight: 510g (body only, w/o battery)

Conquering inner space

Maitani had already had great success with the Olympus Pen series of 35mm half-frame compacts, and the innovative Pen F half-frame SLRs, but now he wanted to do the same thing with the full-frame format. What’s more, he didn’t just want small reductions in the size and weight either – he wanted both to be halved, taking the Nikon F as the reference point. In the end, this proved to be over-ambitious, particularly because it would have compromised durability, but nevertheless he still wanted something that would look and feel significantly smaller than anything else on the market.

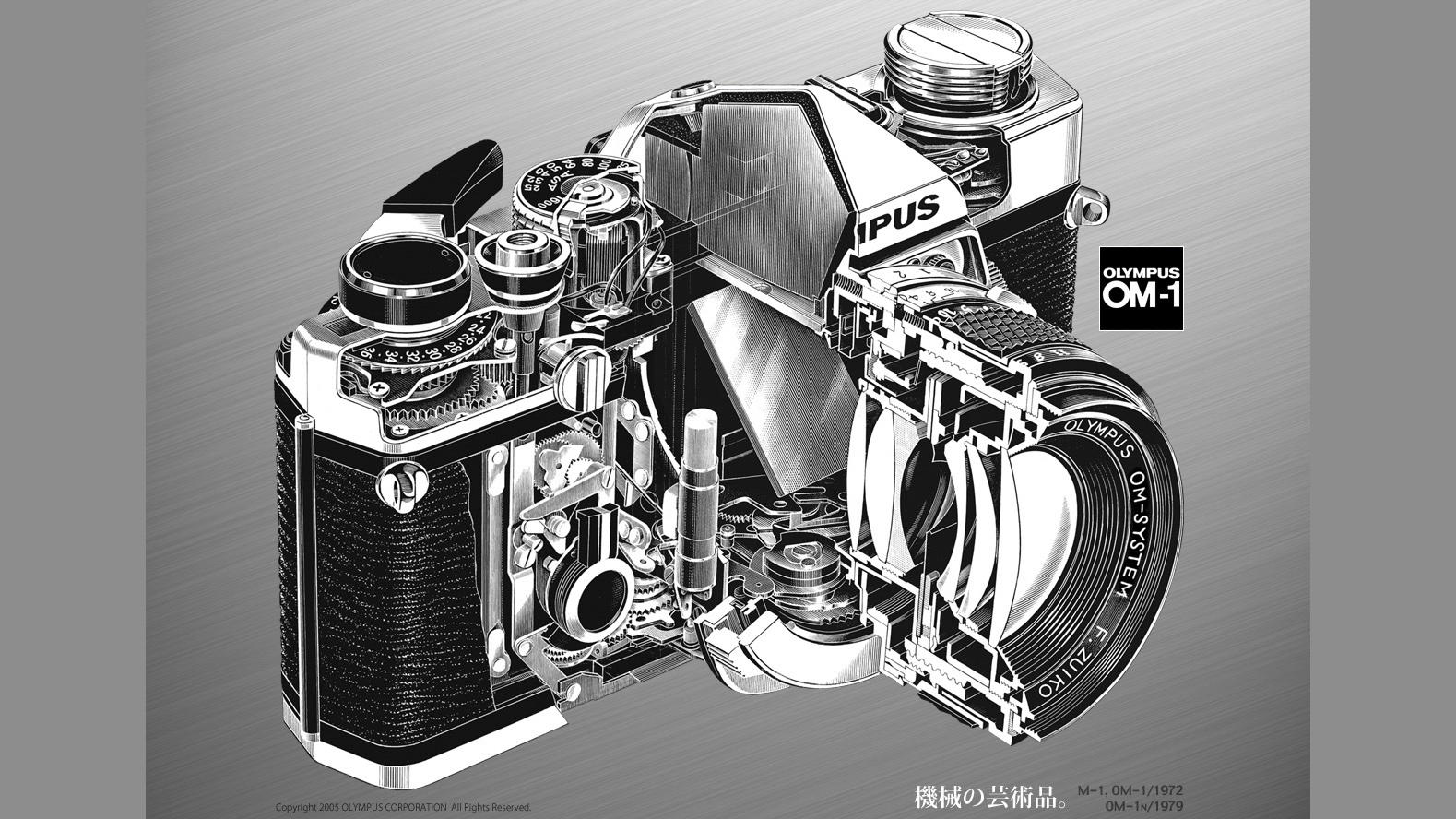

The project was given the green light in 1967 and the challenges were many, but Maitani noted that, “the interior of an SLR is not all crowded; there are crowded areas and empty areas”. The crowded areas were those containing the core functions, such as advancing the film, releasing the shutter, or changing the shutter speeds.

Maitani hit upon the idea of relocating some of these core functions to the less crowded parts of the camera body and this, for example, led to the OM-1 having its shutter speed selector located around the lens mount. In the digital era, anything can really go anywhere inside a camera, but with a mechanical design, there were physical linkages – shafts, levers and gear cogs – to precisely locate, which was why rearranging the internal configuration of the 1960s-vintage 35mm SLR wasn’t as straightforward as it might seem today.

Apart from the reduced size and weight – the initial target was 600g for the body – Maitani was also demanding increased durability. For instance, he wanted the shutter assembly to be good for 100,000 cycles, which was a pro camera spec at the time. He also wanted both the shutter and the reflex mirror mechanism to be quieter in their operations and create less shock. A mini shock absorber was designed to cushion the mirror, which was rather more sophisticated than the simple foam strips that everybody else was using. Alloys replaced brass for the body covers and the pentaprism viewfinder was completely redesigned to eliminate the traditional condenser, further saving weight. Even brass screws were replaced by steel ones, which helped save a few precious milligrams. In the end, the OM-1 body undercut the target weight by a substantial 90g, weighing in at 510g. And despite the camera body being so small, Maitani still wanted a big and bright viewfinder, which was achieved with 0.92x magnification and use of a silver coating (rather than aluminium) on the pentaprism. Additionally, the reflex mirror was multi-coated – a world first – to also help enhance the brightness of the viewfinder image.

Form & function

Fifty years on, the original Olympus OM-1 is still a truly exquisite piece of camera design. Without the optional hotshoe – which looks a bit clumsy – the lines are clean and crisp, and the whole thing is beautifully proportioned. There’s a purity that’s only possible when form and function are so perfectly aligned.

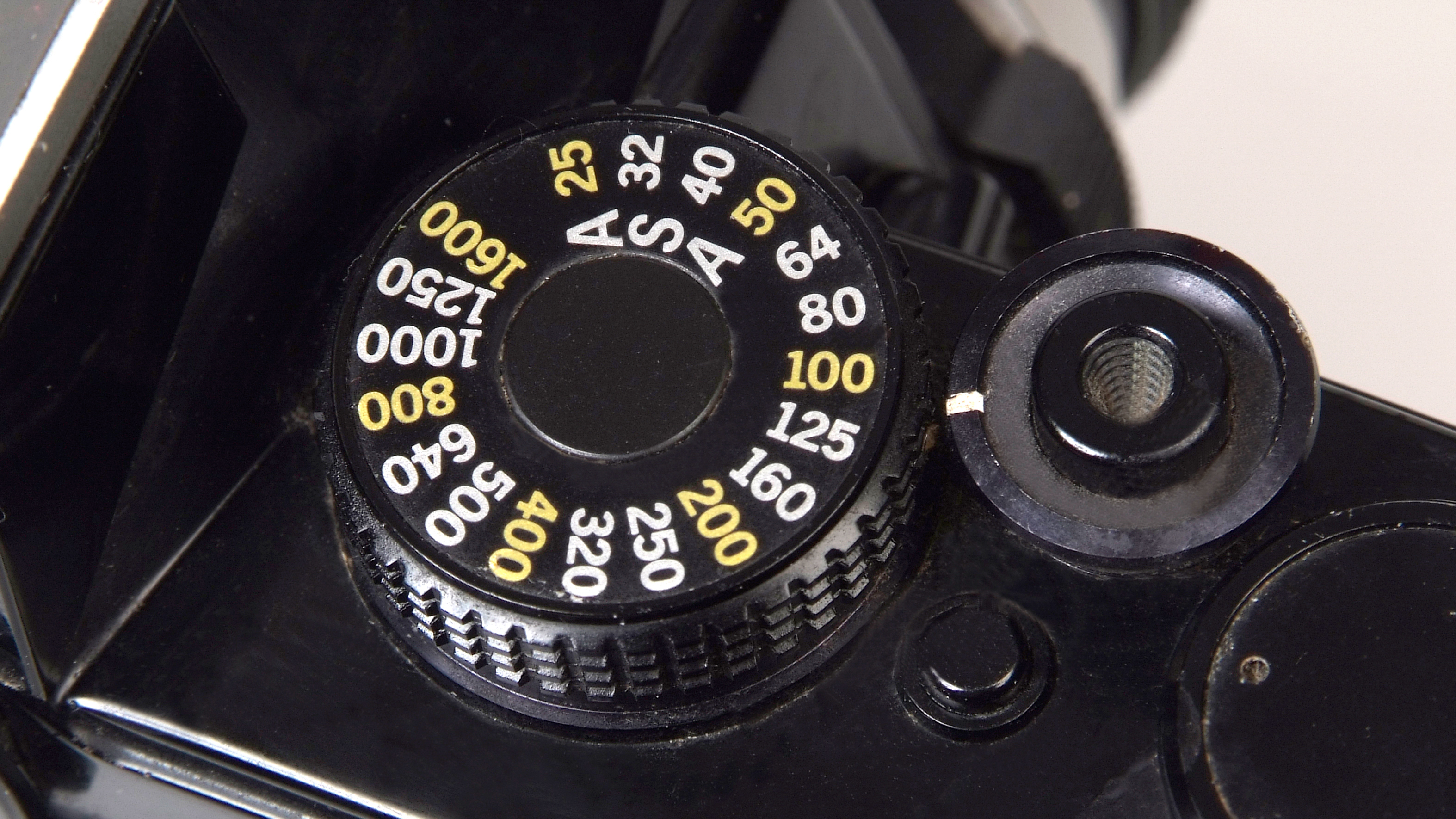

Despite the absence of any aids for comfort, the handling is near flawless and the camera sits beautifully in your hand… with perhaps only the E-M10 series OM-D models being the closest modern-era equals. It just makes so much sense to have the shutter speed selector on the lens mount… so it feels quite natural to move from here to the aperture collar – which is at the front of Zuiko lenses – and back again when changing exposure settings. And, of course, we’ve seen a return to a dial dedicated to ISO setting elsewhere… because it’s still much more convenient than anything else. Equally sensibly, the release lock for the film transport is on the front of the camera rather than in the base, so it’s easier to reach, especially when the camera is on a tripod. And of course the lens release buttons should be on the lens itself… so just one hand is needed to detach it – grip, squeeze, twist, done!

There are some nice design touches too, such as the elegantly long levers that serve as the power switch (since reprised on a number of OM-D models) and the self-timer’s actuator. And the selector lever around the PC flash terminal – which changed the syncing from FP (for flash bulbs) to X – is so much neater than having the two separate connections, which was much more common at the time.

In most other respects, though, the OM-1 was pretty conventional for a mechanical 35mm SLR in the early 1970s. The only luxury is built-in metering, which takes a centre-weighted average measurement that is relayed to a simple needle-type plus/minus indicator in the viewfinder.

The meter used the then-common CdS-type metering cell and was powered by a single 1.35V mercury-type button cell. Mercury cells have long been outlawed, so the only direct replacement these days is the Wein zinc-air battery (MRB625) that has the right voltage. Alternatively, you can use a 675- type 1.3V hearing-aid button battery, but it may be necessary to wedge it in the compartment as there may be slight variations in diameter. You could also fit a 386-type 1.55V silver-oxide battery (commonly used in watches), but you’ll need to adjust the metering by selecting a slower film speed (by two stops) than is being used

The focusing screens were interchangeable – with a choice of 12 initially, later increased to 14 – and the standard option provides both a microprism collar and a split-image rangefinder. Furthermore, you could easily swap them over yourself as they fitted into a frame that cleverly swung down from beneath the base of the pentaprism.

As was also common at the time, the shutter had horizontal-travel cloth curtains – specifically rubber-coated silk – with a speed range of 1-1/1000 second. Flash sync was up to 1/60 second and none of the OM-1 series models had a fixed hotshoe (nor the OM-2 for that matter) and required an optional accessory unit to be fit.

Systematic

Olympus quickly followed up the OM-1 with the ‘MD’ version, introduced in 1974, which could be fitted with a 5fps motordrive or a single-shot auto winder. In fact, the body coupling was there right from the beginning, but blanked off by the baseplate so the earlier cameras could be converted.

The OM-1N appeared in 1979 with a few small revisions, mostly relating to the fitting of dedicated T-series flash guns (via a new version of the accessory hotshoe) and the provision of an LED flash on/OK indicator in the viewfinder. Remarkably, the OM-1N remained in production until 1987, by which time it had been joined by the OM- 2, OM-3, OM-4 and OM-2 Spot Program (which, incidentally, was actually based on the OM-4).

Like the Nikon F, the OM-1 arrived with a huge system of lenses and accessories… it was called the ‘M System’ at the start and then ‘OM System’. The Zuiko lens system numbered 38 – not bad at kick-off – and spanned an 8mm f/2.8 fisheye to a 1000mm f/11 mirror-type supertelephoto. There was also a 75-150mm f/4.0 zoom (then still quite rare), a 35mm f/2.8 shift lens and a total of three macros including a 1:1 80mm f/4.0. Interestingly – and deliberately – all the lenses from 20mm to 200mm had 49mm screw-thread filter fittings.

The accessories included the aforementioned motordrive and auto winder, plus a 250-exposure bulk film back, numerous components for macro photography and – with medical imaging destined to become an important part of the Olympus business – photomicrography products for use with its microscopes. Thankfully, the Zuiko name continues on OM System lenses. As with the Olympus brand, it was also first used in 1936 and, roughly translated from Japanese, means “auspicious light”.

Verdict

For a design that’s now over 50 years old, the Olympus OM-1 still somehow looks and feels quite contemporary. The younger OM-1N model we’ve tested here is still at least 40 years old, yet everything is operating as smoothly and reliably as when it was first taken out of the box. And the mirror/ shutter operation is still extremely quiet even by today’s DSLR standards… in fact, it sounds more muffled than many. Likewise, the viewfinder is certainly as good as anything we’ve seen on the latest DSLRs in terms of brightness… and nobody gets close to 0.92x magnification anymore.

Of course, the OM-2 that arrived in early 1975 (the prototype was shown at the 1974 Photokina) did just about everything better – especially its metering, which used the more responsive SPD sensors and introduced ‘off-the-film’ measurement – with the same gloriously petite body, but it was the OM-1 that stunned the camera world when it was first revealed. It went on to influence 35mm SLR design for decades and was uppermost in the minds of Olympus’s designers when they were working on the E-400 series compact DSLRs and, later, the OM-D mirrorless cameras. And, clearly, the model number that has been so important in its history is now going to help guide the newly-independent camera maker into the future.

Find the Olympus OM-1 on eBAY.com

An OM-1 or OM-1N in immaculate condition with a 50mm f/1.8 should set you back $150 or more – but you can find more battered bodies for much less.

Find the Olympus OM-1 on eBAY.co.uk

An Olympus OM-1 or OM-1N in immaculate condition with a 50mm f/1.8 will cost around £125, but you can find examples for less. Just be mindful that there can be issues that the seller may not even know about.

Read more:

• Best film cameras

• Best film

• Best darkroom equipment

• Best film scanners

• Best Lomography cameras

• Best student camera for studying photography

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.