What is ISO in photography?

Okay… exactly what is ISO in photography? This is what it stands for, what the numbers mean and when you should change them

It may be a simple question: what is ISO in photography? However, the answer isn't quite so straightforward – mainly because it's a term that originated before digital imaging.

So, let's rewind: what is ISO in photography in terms of analog shooting? Camera film comes in different speeds, with a higher ISO rating equating to a ‘faster’ film – which means it is more sensitive to light, enabling you to use faster shutter speeds than you can with ‘slower’ film.

Using a higher-sensitivity ISO is useful for moving subjects (where faster shutter speeds are required) and particularly for shooting in low light. Thus, ISO forms one corner of the exposure triangle – along with aperture and shutter speed.

Okay, but how is this speed measured? A number of different scales were introduced when film was invented, and two of the best known – the American ASA and German DIN scales – were ultimately brought together to create the standardized ISO system.

The best digital cameras, of course, do not use film – but the same ISO scale is still used today to measure the camera’s sensitivity to light. Although the camera’s image sensor cannot be changed the way film can, its sensitivity can be boosted by the camera’s circuitry. This is done with the ISO control.

What does ISO stand for?

So, we've answered "what is ISO in photography". But what does ISO stand for? ISO is the name of the International Organization of Standardization: a body that creates thousands of agreed standards for a huge range of products, procedures, and practices. ISO isn't an acronym and doesn't stand for anything – it simply refers to the Organization.

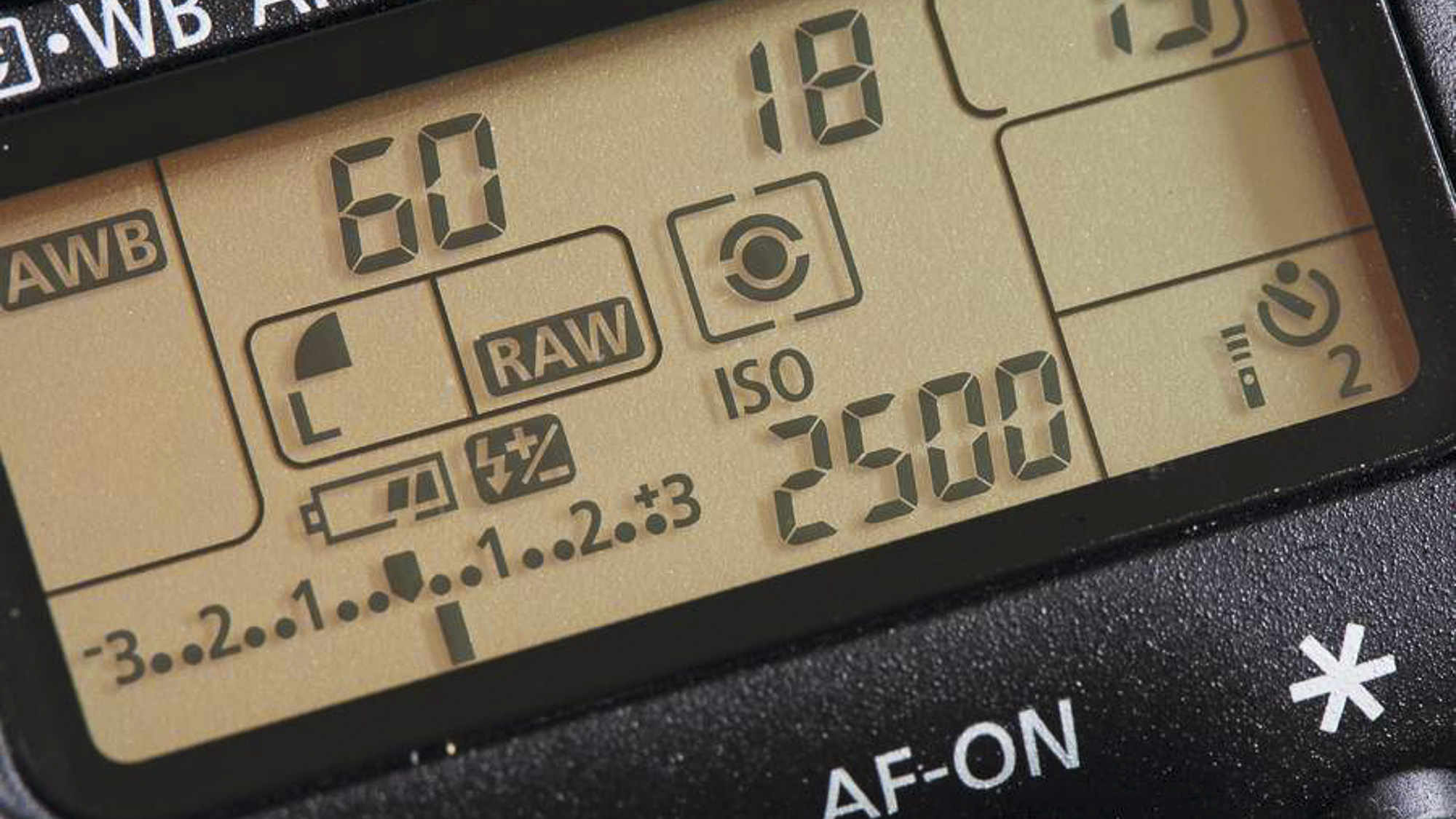

For the photographer, ISO is simply a set of numbers. The base sensitivity – the lowest native setting – of many digital cameras is ISO100. But is typically increased by pressing the appropriate button, rotating a dial, swiping the touchscreen or changing a menu setting. On some cameras, you may even get a separate ISO control dial.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The scale is such that doubling the ISO number doubles the sensitivity of the sensor. So increasing the ISO setting from 100 to 200 means that, to get the same overall exposure, you can use a shutter speed that is half as long (or twice as fast).

Each doubling of the ISO also increases the sensitivity by a full exposure ‘stop’ – with the typical full-stop ISO scale progressing to 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 and so on. The top ISO setting varies depending on the age and cost of your camera. Typical maximum settings range from ISO3200 to ISO819,200. Some of the best low-light cameras are particularly good at handling high ISOs

Confusingly, the top ISO settings on some models are hidden and must be enabled using a custom option called ‘ISO Expansion’ or similar. The reason for this is that each time you increase the ISO setting, you also get a small and cumulative decrease in image quality. So, while cameras boast extremely high or low 'expanded' ISO sensitivities, you may not want to use them!

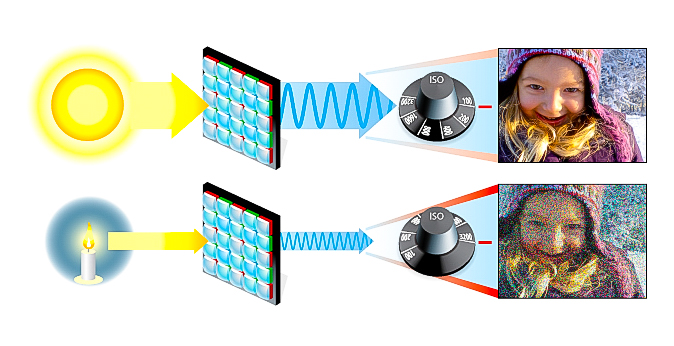

Boosting the picture signal also amplifies impurities in the signal known as ‘noise’. This noise shows up as grain and color mottling in the image – and this gets progressively more noticeable the higher the ISO is set.

When to increase the camera's ISO

Some photographers try to resist increasing the ISO at all costs in search of getting the best, grain-free images. However, pumping up the ISO often actually increases image quality overall, as this simple change lets you use a faster shutter speed – thereby eliminating camera shake. A grainy picture is always better than a blurry one!

A higher ISO can also enable you to use a narrower aperture – increasing depth of field, and thus increasing the resolution of a lens – to give you sharper-looking pictures.

Although higher ISO settings are invaluable in low light, they are not essential for all low-light situations, in fact, if you can keep the camera steady, they are often best avoided. If you are using a solid tripod, the slowest ISO setting (ISO100) is usually the best option – as you can then use a longer shutter speed to make up for the lack of light.

Similarly, if you are using flash, high-ISO settings are not needed (although increasing the ISO will increase the effective range of your flash).

What are the types of image noise?

There are two different types of noise found in digital images. Luminance noise shows up as a speckled pattern, like specks of black sand, and is similar to the grain that was found when using high-ISO black-and-white films. Chromatic noise is colored and looks like the rainbow-like sheen when looking at a patch of oil (and is similar in appearance to the blotchy dye patterns that you saw when enlarging high-ISO color films).

It’s important to look at these two types of noise separately – as each can be reduced using different tools during the editing stage. These are often provided as separate noise-reduction sliders by a RAW converter (such as in Adobe Photoshop’s Camera Raw utility). Specialist software, such as DxO Dfine , is particularly useful for reducing noise without sacrificing detail.

So, what is ISO in photography? It's a whole lot of things – and all of them are important!

You might also like…

Take a look at out A-Z Dictionary of photography jargon for more common and confusing camera terminology. We can also help you answer other questions like what is exposure in photography and what is aperture in photography.

James has 25 years experience as a journalist, serving as the head of Digital Camera World for 7 of them. He started working in the photography industry in 2014, product testing and shooting ad campaigns for Olympus, as well as clients like Aston Martin Racing, Elinchrom and L'Oréal. An Olympus / OM System, Canon and Hasselblad shooter, he has a wealth of knowledge on cameras of all makes – and he loves instant cameras, too.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.