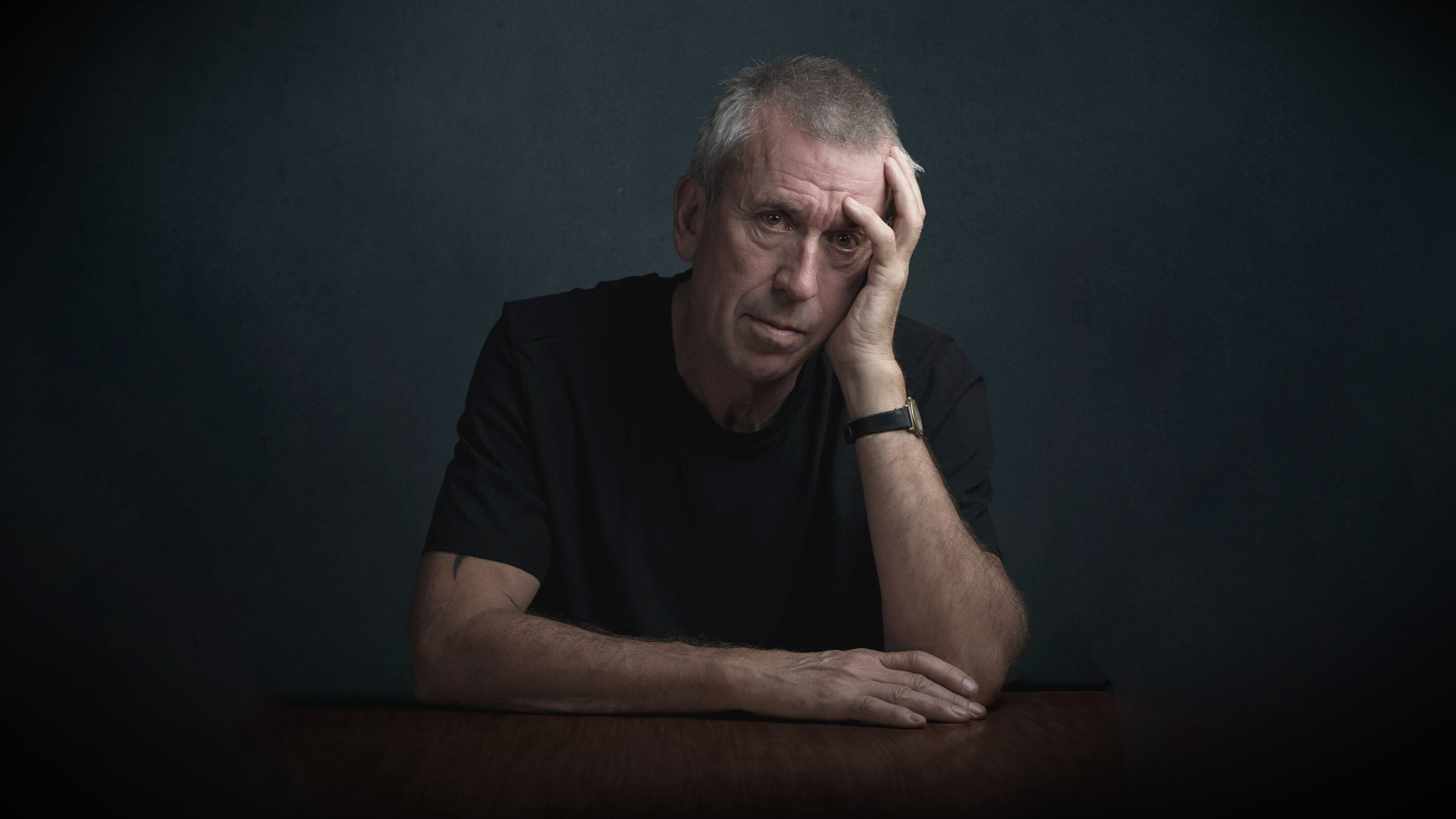

Do we really need all that bokeh? Just because your camera's lens can blur everything doesn’t mean it should

Why you don't need the fastest lens to capture great photographs

Lately, I’ve been thinking about depth of field, or more specifically, about how obsessed we seem to have become with making it as shallow as possible.

Everywhere I look, it feels like the done thing in photography is to melt the background into a dreamy, creamy blur, leaving just a sliver of the subject in focus. And I get it. Something is alluring about that look. It feels expensive. It feels professional. It’s cinematic, too, which I suspect plays a big role in all this.

But I can’t help wondering; when did this become the default? And is it always the right choice?

Photography hasn’t always been like this. In fact, when I think about the great photographers whose work has stuck with me over the years, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Joel Meyerowitz, William Eggleston, Arnold Newman, and Daido Moriyama, shallow depth of field rarely seems like a priority. Most of them, whether consciously or not, seemed to embrace a deeper focus, allowing more of the world into the frame.

Meyerowitz’s street scenes are often buzzing with sharp detail from edge to edge. And with portraits, it’s not as straightforward as it seems either. Sure, shallow depth of field can separate a subject from the background, but I often think about Arnold Newman’s environmental portraits, where the surroundings aren’t distractions at all, but essential parts of the story. Annie Leibovitz, too, often keeps enough of the scene in focus to suggest something more, something beyond just the face.

Of course, I’m not saying there’s no place for shallow depth of field. There absolutely is. It can be beautiful, and sometimes it’s exactly what a photograph needs compositionally. But I do wonder if it’s become a kind of crutch, especially among newer photographers.

I’ve lost count of how many conversations I’ve had where someone’s first instinct is to shoot everything wide open, as though that’s the done thing. The idea of closing the aperture and letting more of the frame come into focus, could be equally valid doesn’t seem to cross their mind.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

I’ve been guilty of this too. For a long time, I bought into the myth that a faster lens automatically meant better photos. You're certainly paying for it, so why not use it right? But lately, I find myself reaching for simpler tools. I’m perfectly happy shooting with my GF 35-70mm kit lens and GF 100-200mm that only opens up to f/4.5 or f/5.6. It slows me down, makes me think more about composition and light, and forces me to ask if I really need that blur? More often than not, the answer is no.

You don’t always need to fork out for the fastest lens on the market. Not being able to shoot at f/1.2 doesn’t necessarily mean you’re compromising anything. If anything, it might just open the door to a different way of seeing.

I sometimes wonder if this modern obsession with shallow depth of field has less to do with photography itself, and more to do with cinema. In film, it’s long been a powerful compositional tool and a way to subtly guide the viewer’s attention, to direct the eye through a moving scene.

And now, with photography consumed mostly on screens, perhaps we’ve unconsciously absorbed that language. Shallow depth of field pops on a phone screen. It simplifies an image instantly. But it makes me curious: how much of this is a result of the context in which we view photographs, rather than what the images need?

It would be an interesting exercise, next time you’re at an exhibition of a well-known photographer who made work before the constant use of screens, to look at the prints and notice how often a shallow depth of field plays a role. My hunch is that in the physical world of prints, it’s far less dominant than it seems online.

I don’t think there’s a right or wrong here. It’s just something I’ve been sitting with, the idea that photography isn’t always about isolating things. Sometimes it’s about including them. About letting everything sit together, side by side, in focus. Just because a lens can blur the background into oblivion doesn’t mean it should.

you might also like

Check out our guides to the best coffee table books on photography and the best cheap lenses.

Kalum is a photographer, photo editor, and writer with over a decade of experience in visual storytelling. With a strong focus on photography books, curation, and editing, he blends a deep understanding of both contemporary and historical works.

Alongside his creative projects, Kalum writes about photography and filmmaking, interviewing industry professionals, showcasing emerging talent, and offering in-depth analysis of the art form. His work highlights the power of visual storytelling.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.