The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

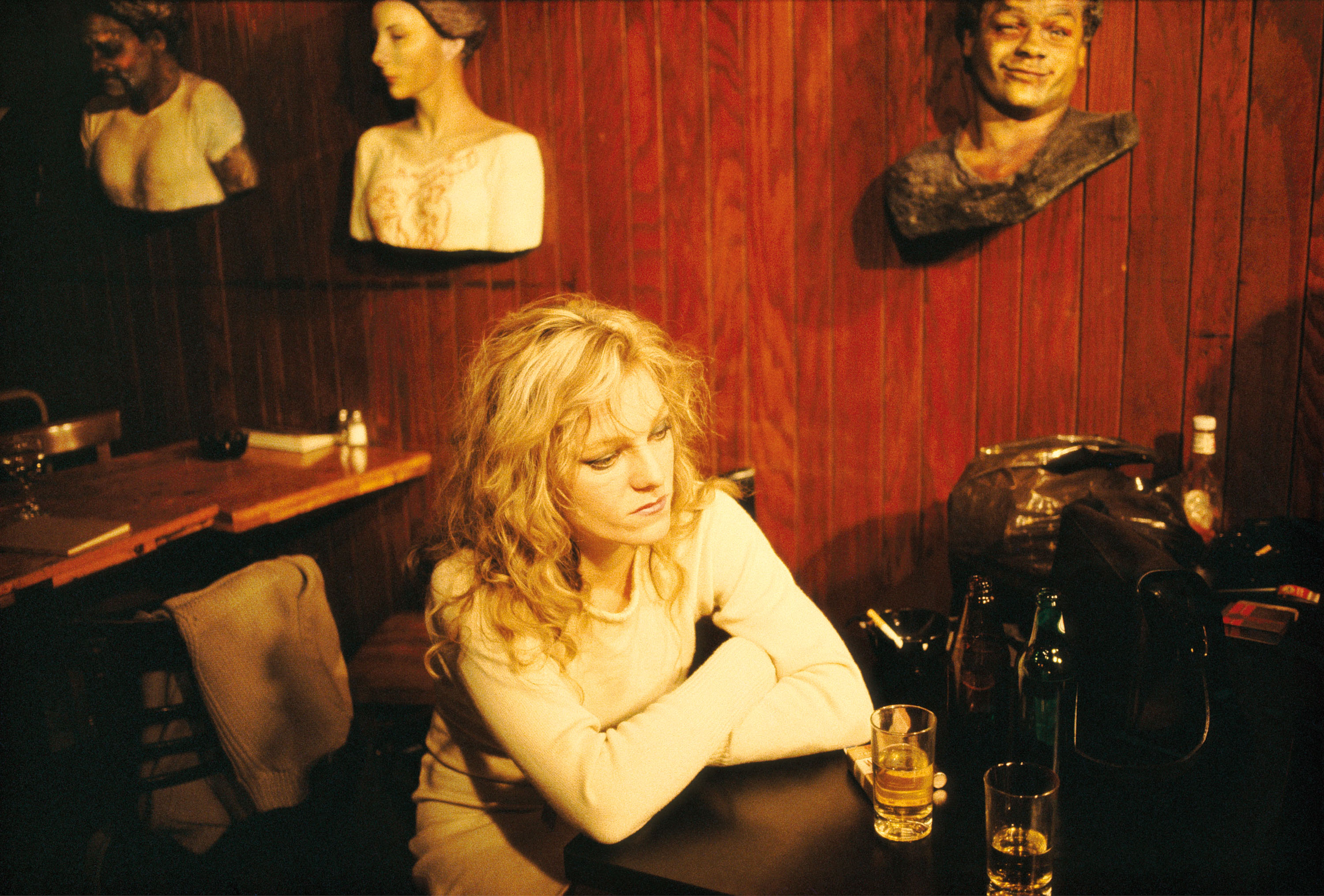

When Nan Goldin shot the photographs that would be published in 1970s as The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, she didn't really know what she was doing with light. As she told the Guardian years later, "That series is stark. It's all flash-lit. I honestly didn't know about natural light then and how it affected the color of the skin because I never went out in daylight."

For some, that would be a career-limiting admission. For Goldin, it was precisely the point. Now, from January 13 onwards, all 126 images from the seminal photobook will be shown at Gagosian in London. It's the first time the complete body of work has been exhibited in the UK.

The timing feels significant for anyone interested in how photography moved from the margins into the centre of contemporary art discourse. Because what Goldin achieved with her on-camera flash and Cibachrome prints was nothing short of a technical and aesthetic revolution.

Slideshow that ate the art world

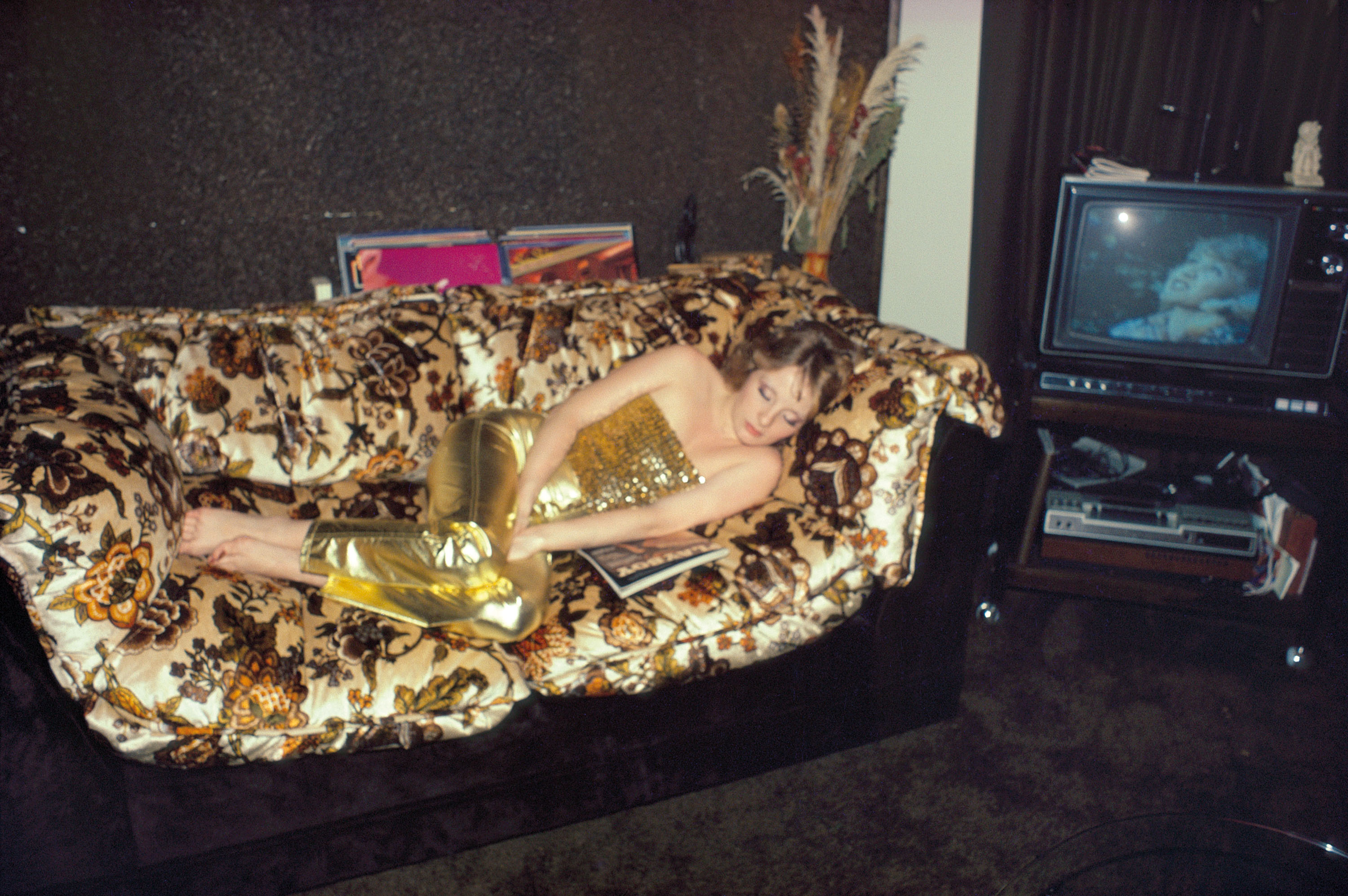

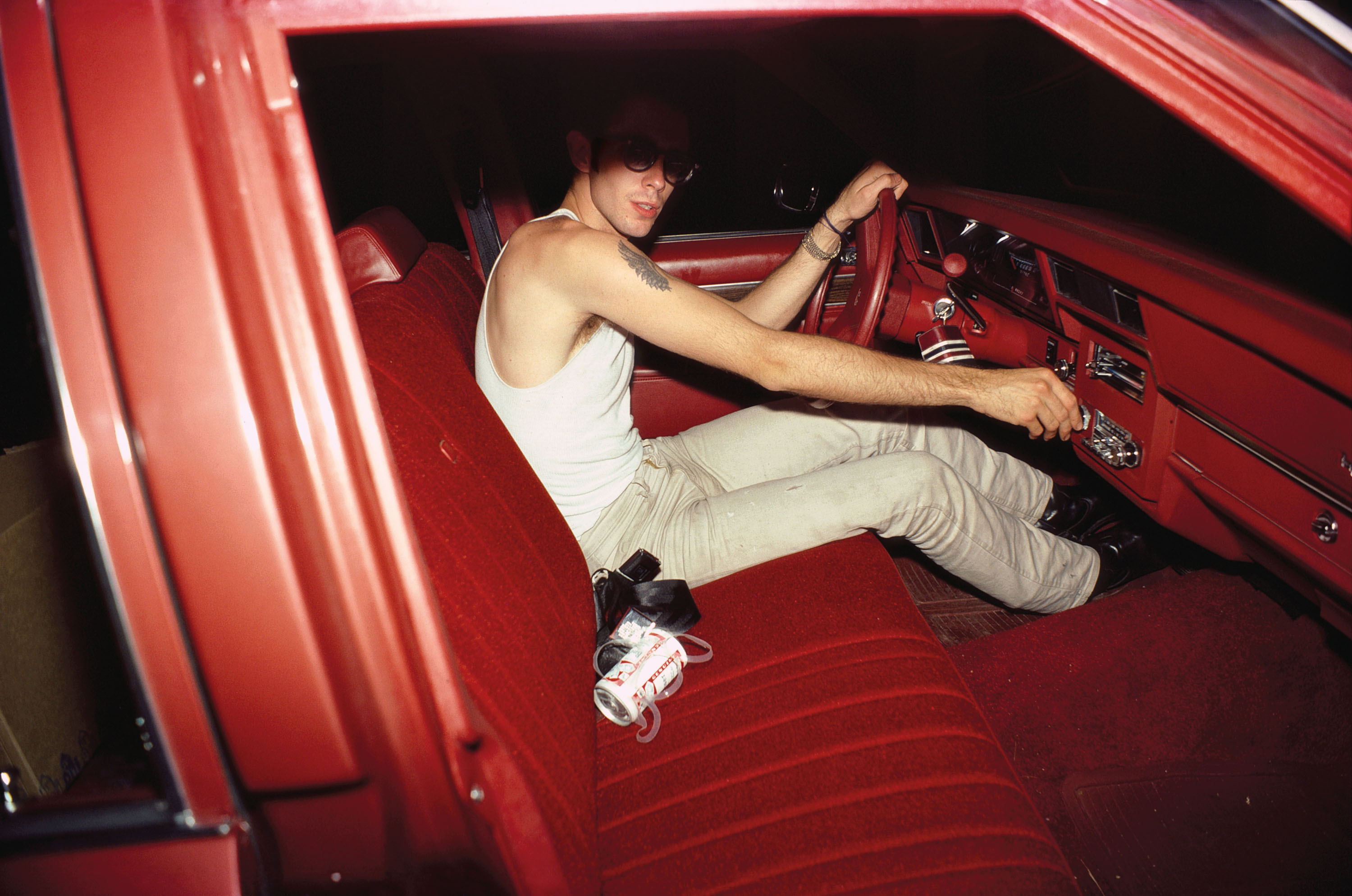

The genesis of Ballad began in New York, where Goldin moved after graduation and began documenting the post-punk new-wave music scene, along with the city's vibrant, post-Stonewall gay subculture of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Before the series became a book, it was a constantly evolving slideshow screened in New York nightclubs, accompanying everything from Frank Zappa's birthday party at the Mudd Club to live performances by the Del Byzanteens, a live band featuring Jim Jarmusch. The audience's immediate reactions shaped its form night after night.

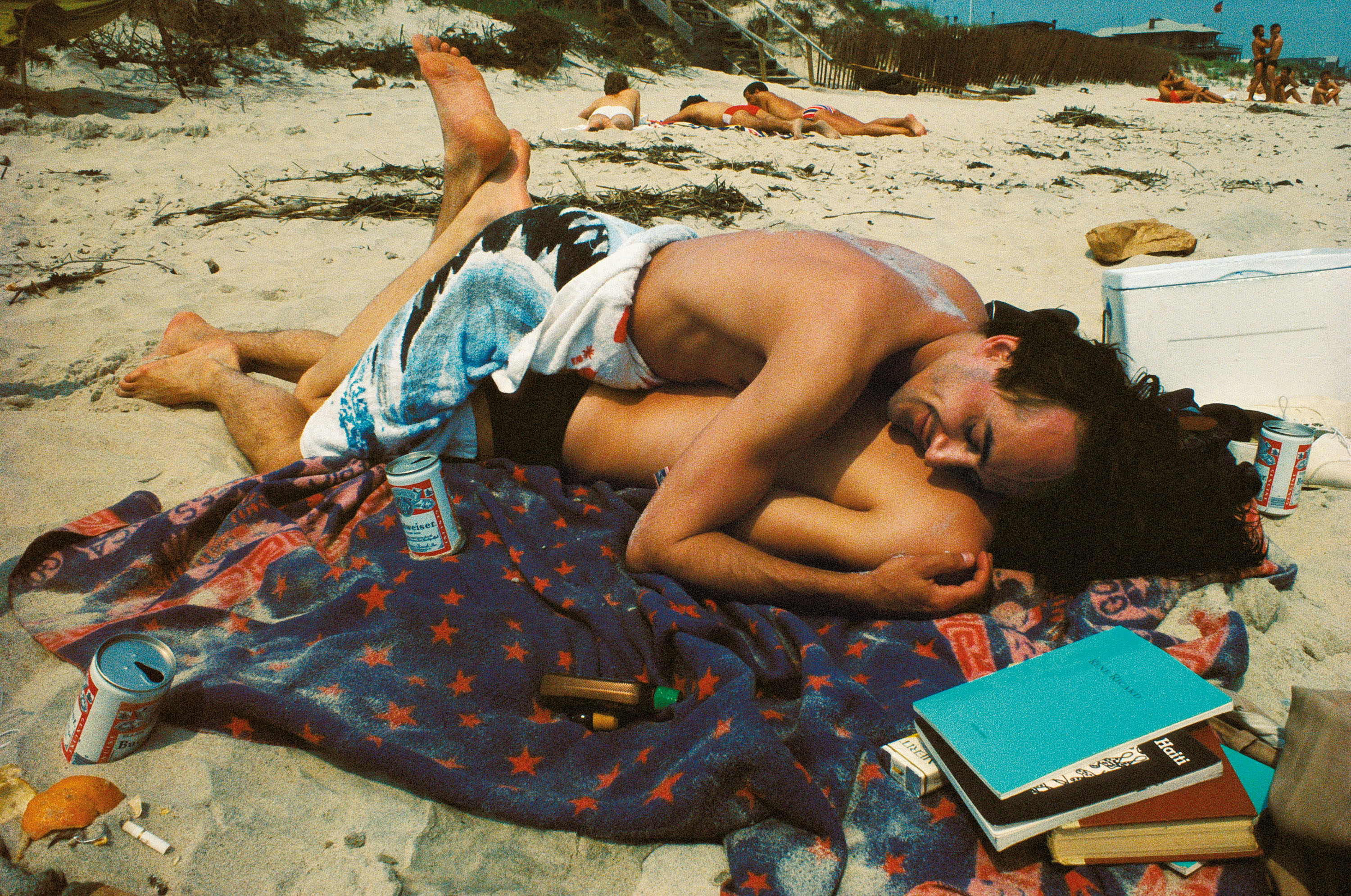

This was photography as performance art, as living document. Crucially, it was photography made by someone who was part of the world she documented, not observing it from outside. "I don't select people in order to photograph them; I photograph directly from my life," Goldin says today. "These pictures come out of relationships, not observation. They are an invitation to my world."

That insider status, combined with her flash-lit snapshot aesthetic, upended everything the art establishment thought photography should be. Here was work that was technically "wrong" by conventional standards, deeply personal to the point of exhibitionism, and yet somehow spoke to universal experiences of intimacy, power, gender, and loss.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Camera as memory machine

Shot between 1973 and 1986 in the bars, bedrooms and bathrooms of New York, these photographs document what Goldin called her tribe with unflinching honesty. The flash creates harsh shadows and saturated colors. The compositions are often awkward. But the emotional truth shines through, and that's what makes these pictures special.

By the time Whitney Biennial screened the slideshow in 1985 and Aperture published the book in 1986, Goldin had created what many consider the most influential photobook ever produced. It's now in its 23rd printing, a remarkable achievement for work that began as something shown to friends in nightclubs.

Tthe photographs in Ballad document a world that no longer exists. Most of Goldin's subjects have since died; friends are preserved only in these flash-lit frames. The work has become both a celebration of life lived intensely and a memorial for a lost generation.

Lessons for today

"I'm still impressed that generation after generation finds their own stories in Ballad, keeping it alive," Goldin reflects today. And surely, that's the ultimate validation for any creative practitioner: creating work so rooted in personal experience that it becomes universal.

For photographers working in 2026, when everyone has a camera in their pocket and social media has made the snapshot aesthetic ubiquitous, Ballad offers some important lessons. That technical perfection can be overrated. That intimacy and honesty matter more than formal beauty. And that sometimes, not knowing the "rules" frees you to make work that changes the rules entirely.

Forty years on, in an age when we're drowning in images, Goldin's flash-lit intimacy still cuts through. That's the mark of work that matters.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is at Gagosian, 17-19 Davies Street, London, from January 13 to March 21, 2026.

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.