Why I think the 'first three, no flash' rule when photographing gigs needs updating

The industry standard 'first three, no flash' policy has been in place at live music events for decades and needs reconsidering

Would Pennie Smith have managed to capture the iconic shot of Paul Simonon smashing his bass guitar, that later became The Clash's album cover for London Calling, had she been escorted out of the pit after the third song?

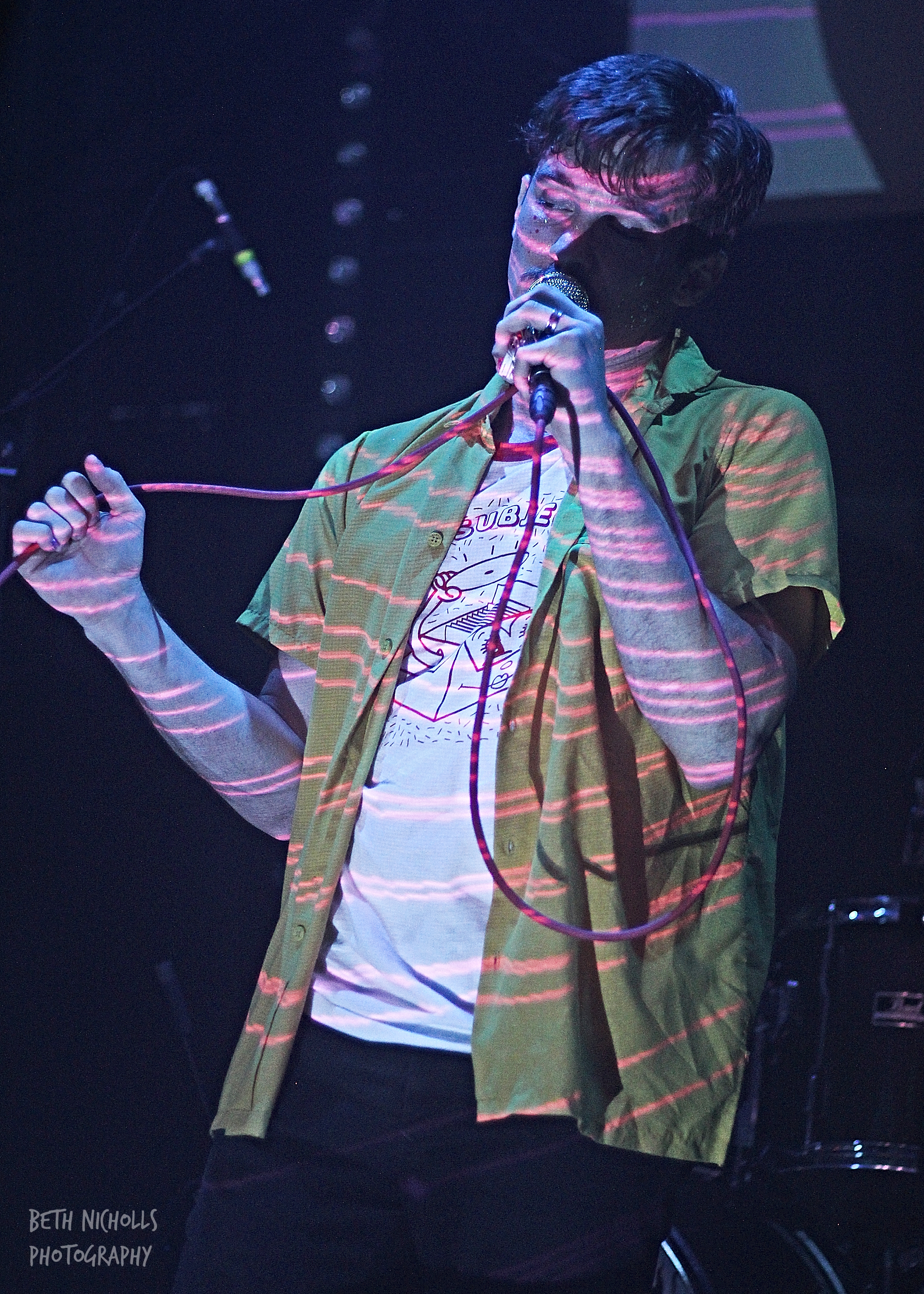

Our perception of iconic musical legends is determined in part by how they were captured during that time period, and it's rare to find such a raw image resembling this energy in today's press, with musicians arguably behaving better on stage and the "first three, no flash" policy adding restrictions to what can be captured.

• Wondering what the best camera settings for live music photography are?

Contemporary debates in the field of concert and live music photography have been circulating for quite some time and I think we need to address the industry standard rule that prohibits photographers from using flash and shooting after the first three songs of an artist's setlist. I'd like to start by saying that I think the 'no flash' part of the rule is completely understandable, and I agree that it should not be tolerated.

Stage lights can be distracting enough for a performer without the added blinding from an unexpected camera flash, and if we're being honest, it really isn't necessary if your camera performs well in low-light or has an extensive ISO range. With the exception of film cameras and granted permissions, you should never be using flash at a gig, especially if you're shooting from the photo pit.

With that cleared up, I think it's important to note the origins of the first three, no flash policy and how it came into being. In a 2009 interview with Chicago-based music photographer, Paul Natkin, he suggests that It started in the 80's. "Bruce [Springsteen] would go up on stage, and there would be 50 photographers, all shooting flashes in his face...he walked off stage one night and said, 'we have to do something about this'".

Paul continues, "somebody said, 'why not just let them shoot the first fifteen minutes?'...at a normal rock show, a song is about five minutes. Somebody said, let's just let them shoot the first three songs. So it started with him and people in that era. It was also that MTV started around that time, and everybody wanted to look perfect, the way they looked in their videos."

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

One thing I found particularly interesting about this interview with Natkin was when he shared an anecdote of a Chicago band, Jesus Lizard, who once asked him “Why is it that as soon as our show starts getting really good, all of the photographers pack up their stuff and leave?” giving Natkin the realization that most bands aren’t aware of the three-song rule and, in fact, it’s up to the band and not the venue to decide how long photographers are permitted to shoot for.

This led to Natkin explaining the policy to Jesus Lizard who, following the conversation with Natkin, permitted photographers to shoot their entire set at Lollapalooza during the 90s that resulted in a sunset clad photo of them crowd-surfing that made the cover of the New York Times.

It could be argued that the rule also exists as a result of music mags like New Musical Express (NME), who during the 80s cared so little for the reputation of a musician that it would deliberately select pictures of rock royalty photographed with their eyes closed or tripping over for its cover pages, as told in The History of the NME, a fantastic book by Pat Long.

Today’s press certainly know better than to feature unflattering images or start an online twitter feud with a musician, and are aware of how to protect themselves from being politically sued for defamation. So we've now established how this rule came into existence, but why does it still exist in today's industry? Or at least why has it not been updated and still retain outdated measures set in place during the 80s?

I had always shot from within the crowd when I first started out as a music photographer, granted I was only 14 years old and finding my feet, but it wasn’t until moving to Brighton and beginning to acquire photo passes that I was being abruptly escorted out of the photo pit midway through shooting a band at Concorde 2, and I didn't understand why. The more gigs I shot, the more I began to question the necessity of this policy, the main issue for me as a slow shooter being the lack of time you’re provided to capture the “ultimate” shot.

Enforcement of the first three, no flash photography policy can be dependent upon venue size as well as press and media requests made by the artist and their PR. Many larger bands now employ their own tour photographers with access all areas to shoot each show and backstage portraits, understandably revoking the need for press photographers if a band has their own photographer employed.

While studying Music Journalism at uni, I conducted action and survey research that proved when in smaller local venues, around 8/10 people had no idea that the first three, no flash policy existed. All venue managers, promoters and security I spoke with were aware that some sort of permission was granted for me to have my camera at the show, however the idea of only being allowed to shoot three of the songs was baffling and unheard of to them.

On the flip side, there are a number of photographers who believe that if you can’t capture the images you need in the first three songs of a setlist, then you shouldn’t be in the business. A fair argument, though, the first three songs from my own experience can be the dullest and result in the most boring images, especially in smaller venues as the band begins to warm up. This is dependant too of course on the production scale of the show and lighting performances.

With larger arena shows, the best shots you capture will likely be towards the end of the night when the fancy pyrotechnics and confetti cannons emerge, with punk bands really getting into the swing of things with jumps and water spits into the crowd.

It's worth noting that most venues do allow photographers to continue shooting from the crowd after leaving the pit to get those wider "atmosphere shots", though I often felt awkward re-entering the busy crowd and having to bother people by navigating through them to the perfect spot, while also protecting my gear from airborne beer.

The other side of this debate is that the three song deadline allows photographers on commission to relax and enjoy the rest of the show at their own leisure, without pressure of having to shoot an entire show or setlist. While I can definitely understand the benefit of this, I think ideally a photographer should be allowed to choose if they stay or if they go (pardon The Clash pun) and have options to return to the pit at any time throughout the show to keep trying for the winning shot.

I think there needs to be a revision of the first three, no flash policy at live events, not necessarily revoking the rule, but adjusting it to benefit both parties in a more trusted time of press photography. There are certainly things to consider such as the photo pit space itself, as during shows in heavier music genres security are often required to lift crowd-surfers over the pit barrier, a clearer space with no photographers in the pit constantly would surely benefit keeping the crowd safe.

I'm no expert, but having a photographer choose their own three songs throughout the set may be a better compromise, able to shoot both the beginning and the end of a show, with only one or two photographers shooting per song, or maybe having a song (or multiples) allocated to each photographer that they may shoot during.

More clarity and attention to the rule is definitely a must, making bands aware that they have the power to allow photographers to stay for the full set, as well as making photographers (and smartphone crowd shooters) aware of the common courtesy to not use flash or be a hindrance to others.

What do you think of this policy? Had you heard of it? Let us know by commenting on our social feeds under the article.

• Read more:

How to photograph live music

Let the music play! Tips for photographing live music

How to photograph a live band

Abbey Road Studios Music Photography Awards reveals Icon Award Winner

Legendary album covers on display in 'For the Record'

Beth kicked off her journalistic career as a staff writer here at Digital Camera World, but has since moved over to our sister site Creative Bloq, where she covers all things tech, gaming, photography, and 3D printing. With a degree in Music Journalism and a Master's degree in Photography, Beth knows a thing or two about cameras – and you'll most likely find her photographing local gigs under the alias Bethshootsbands. She also dabbles in cosplay photography, bringing comic book fantasies to life, and uses a Canon 5DS and Sony A7III as her go-to setup.