This winter, the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) is presenting Still Glasgow, an ambitious photographic survey drawn from Glasgow Life Museums’ collection.

Opening November 29 and running until April, it features more than 80 works spanning from the 1940s to today. And together, they make a persuasive case that Glasgow’s appetite for change shapes not just what’s photographed, but how.

“Glasgow is a city that has energy, creativity and a history of invention and change,” says curator Katie Bruce. Plenty of industrial cities could claim the same, but this exhibition suggests something more distinctive. Glasgow doesn’t just allow experimentation; it demands it. This is a city that refuses to be photographed the same way twice.

The idea came when Bruce and Malcolm Dickson from Street Level Photoworks visited the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre. What they found wasn’t a single aesthetic tradition, but a jumble of competing visions; all trying, and often failing, to pin down a city in constant motion.

The range of work is striking. Oscar Marzaroli’s 1960s street photography set one template for seeing Glasgow: lyrical, humanist, full of dignity in tenements and shipyards. Decades later, Roderick Buchanan’s 1999 film Gobstopper turns the everyday experience of holding your breath through the Clyde Tunnel into conceptual art. Both claim to show the “real” Glasgow. Both are right.

Constant reinvention

Some cities seem to have fixed photographic identities. Edinburgh? Castles and Georgian symmetry. Liverpool: docks and Beatles nostalgia. But Glasgow keeps shedding skins. The Red Road Flats once symbolised municipal ambition, then social failure, then nostalgia. Iseult Timmerman’s 2015 photos, taken before their demolition, capture a city already looking ahead.

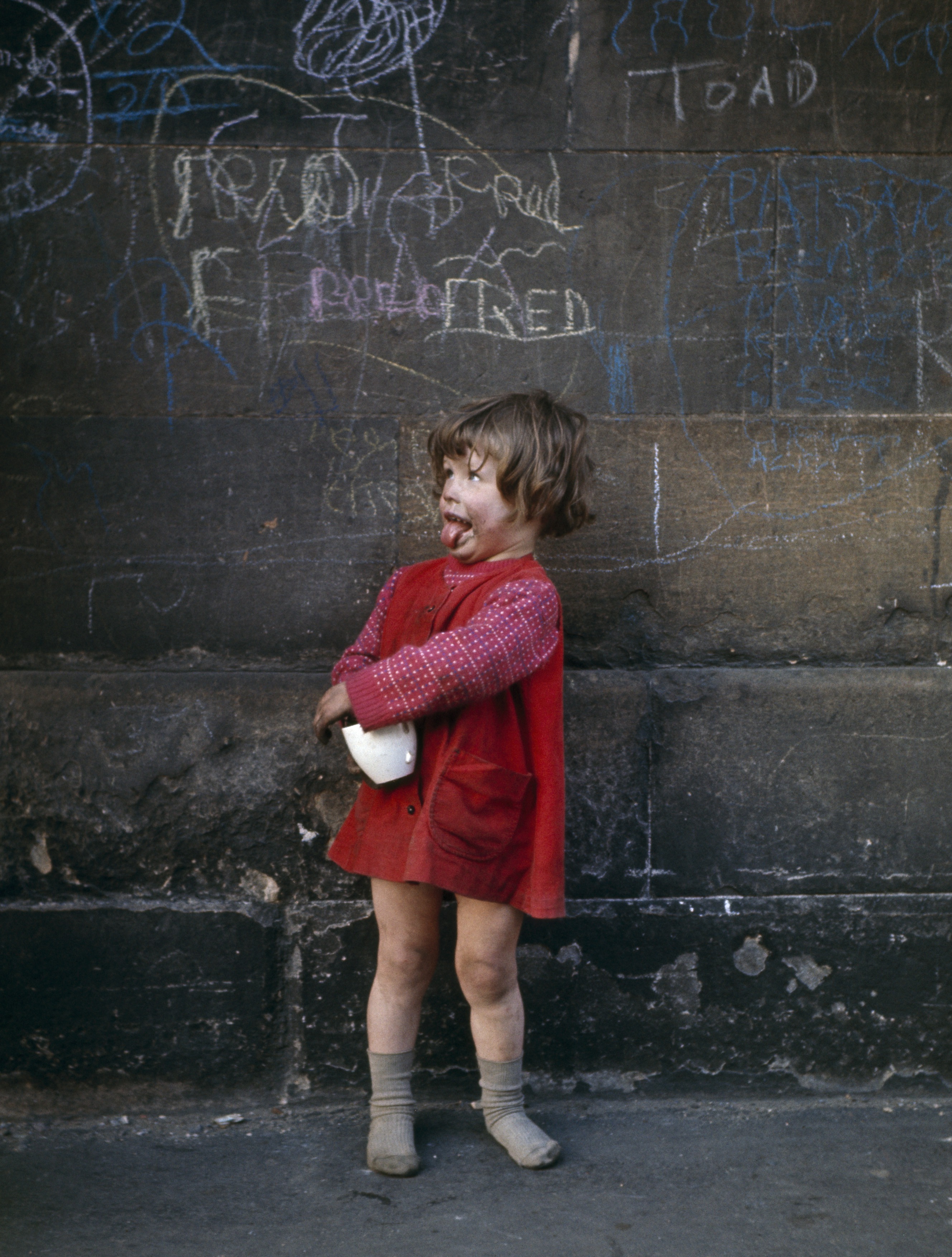

Yes, Glasgow trades heavily on its past, but its best photographers pull back against nostalgia. Eric Watt’s 1960s photo of a girl at a chalk-marked wall could easily slip into sentimentality, but doesn’t; because Watt saw children not as picturesque subjects, but as participants in the city’s self-creation. Meanwhile, contemporary contributions from Glendale Women’s Café and Romano Lav highlight how reinvention continues in communities long ignored by the photographic establishment.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Bruce’s curatorial statement says the exhibition “looks beyond nostalgia and asks how the city can imagine its future.” And this isn't just rhetoric. Glasgow’s visual history is full of attempts to freeze it in time: crumbling tenements, fading industries, lost working-class authenticity. But the strongest work here resists that impulse, and instead shows what genuine creative engagement looks like.

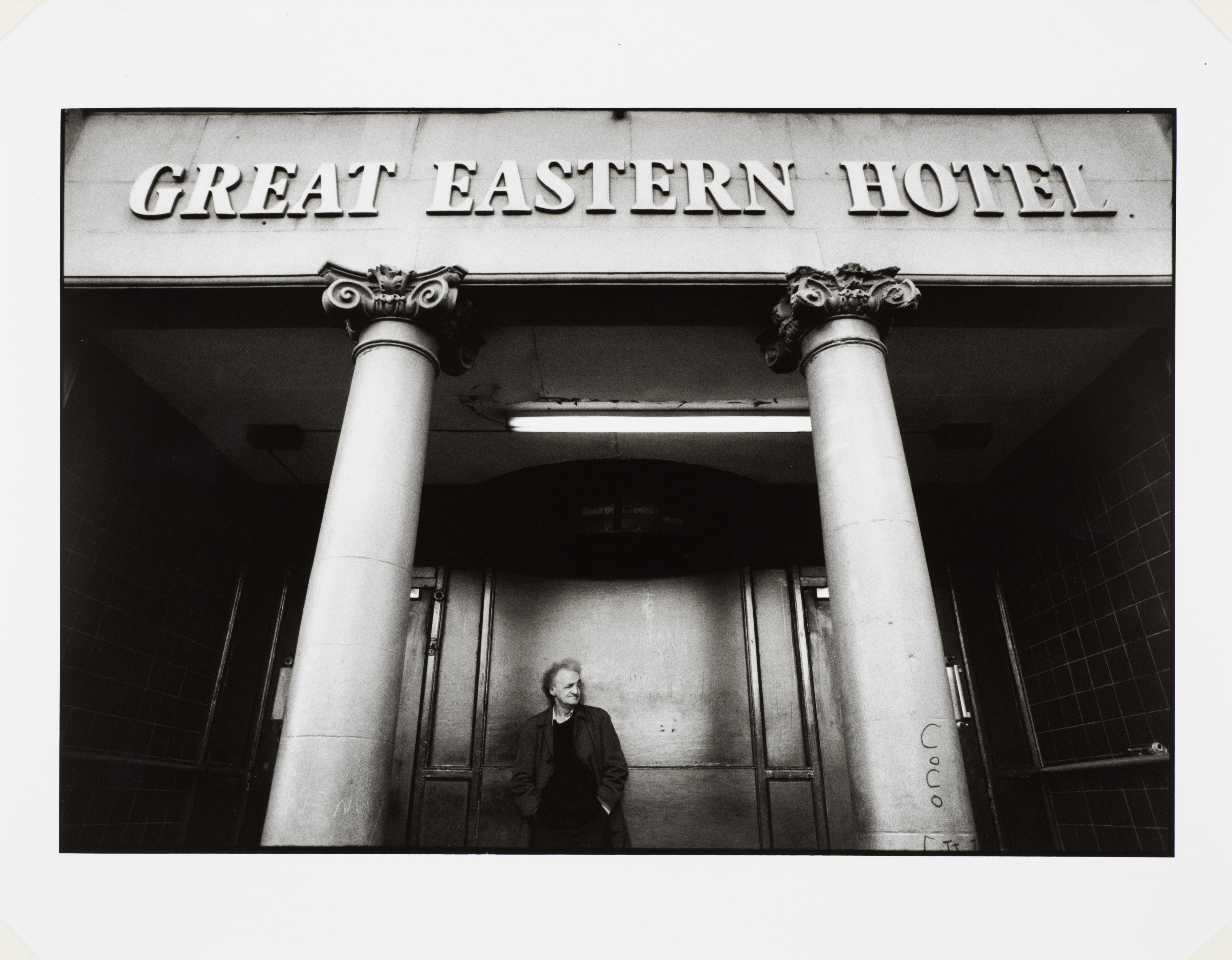

It’s not about pointing a camera at interesting subjects; it’s about finding new ways to express what the city feels like. Jane Evelyn Atwood’s 1994 portrait at the Great Eastern Hotel captures transience and vulnerability. David Eustace’s 1993 Buskers Portfolio documents street performers embodying the city’s resilience. Elsewhere, Alan Dimmick’s portrait of Franz Ferdinand reflect how Glasgow’s music scene generates its own visual culture.

In short, Glasgow’s “history of invention and change” plays out in its photography as restlessness. The city refuses to settle into one identity. Post-industrial, yes, but also a university town, music hub, architectural showcase, immigrant destination and cultural capital; each producing its own version of Glasgow.

For photographers, that’s both challenge and opportunity. Glasgow rewards experimentation but defies definitive statements. Its energy isn’t something to capture; it’s the force pushing photographers to keep finding new ways to see.

Still Glasgow runs from November 29 2025 – April 2026 at the Gallery of Modern Art, Royal Exchange Square. Admission is free.

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.