The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The population of the world reached 8 billion in 2022. That's a massive number. But want to hear an even bigger one? Global smartphone shipments have exceeded 14 billion over the past decade, according to a report from AltIndex.com based on data from IDC (International Data Corporation).

If proof was ever needed, this immense figure underscores the ubiquity of smartphone cameras and their impact on the photography landscape. Especially at a time when sales of digital cameras are going into decline. (For more on that, see our article Japan just sounded the death knell for digital camera sales.)

Despite recent challenges in the market, including component shortages and longer replacement cycles, the sheer volume of devices in circulation is staggeringly high. That said, it's not all been a smooth, upward curve.

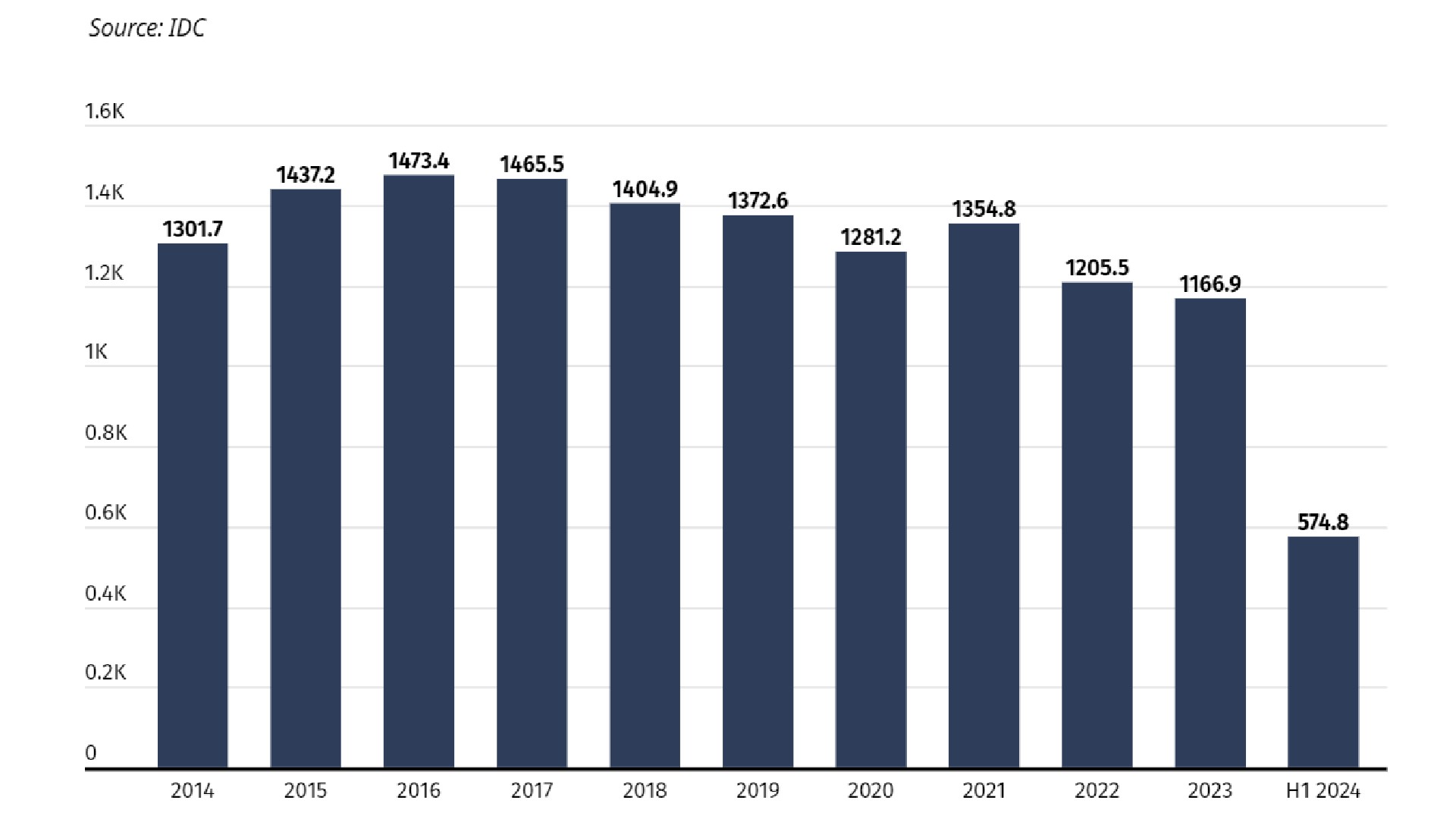

The report notes that the biggest smartphone sales in the past decade were during 2015-17, with an average of 1.4 billion shipments per year. Since then, growth has been impacted by component shortages, inventory build-up and longer replacement cycles, resulting in a $15 billion sales drop over 2018-20. Although 2021 saw sales recover, they fell by another 13% in 2022 and 2023.

The first half of this year, however, has seen sales rise by almost 40 million year-over-year, to 574.8 million.

Ultimately, though, these headwinds and setbacks can't mask the overall picture: smartphone sales are simply enormous. And crucially, more and more of them have the kind of advanced camera features once exclusive to high-end models.

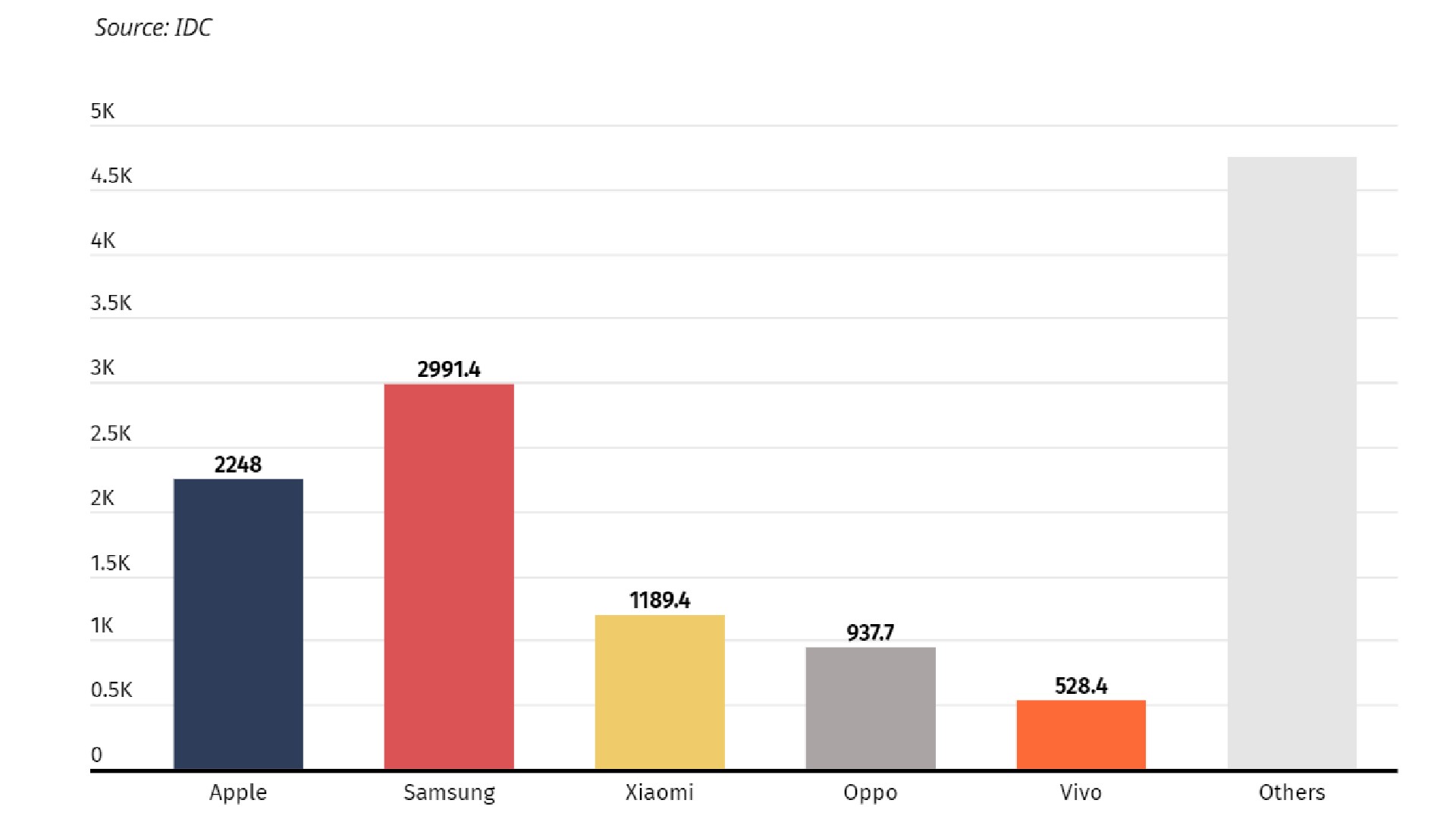

While Samsung, followed by Apple, leads the pack of smartphone manufacturers, Chinese brands like Xiaomi, Oppo and Vivo have shown remarkable growth, and typically these companies are pushing the boundaries of smartphone camera capabilities at mid-range and even low prices.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Xiaomi alone has shipped over one billion devices, and these devices are no slouches when it comes to digital photography. Take the Xiaomi 14 Ultra, for instance; which our reviewer described as "more camera than phone".

In short, we're seeing a worldwide democratisation of technology that means more people than ever have access to sophisticated mobile photography tools. So what does all this mean for photographers?

"Why should I pay?"

The stark truth is that the majority of people now have a high-quality cameras in their pocket. Not only that, they know how to use them, and even if they don't, AI features such as those in the Google Pixel 8 Pro are increasingly taking over and turning bad photos into good ones, without people needing to even click on a filter. And that means professional photographers will increasing face the perception they've become irrelevant.

Yes, we know that isn't, and will never, be true. The art of photography isn't just about the technical skills; there's so much more to capturing an incredible image than that.

But convincing others of this, when the AI-enhanced smartphone pictures they've just taken without any effort look pretty decent? That's another story.

To a certain extent, you've probably heard all this before. Ever since the introduction of digital cameras, pro photographers have been battling with the argument that "anyone can take a photo... why should I pay you?"

But I'd argue that as we reach smartphone saturation, as cameras get better at taking photos and onboard software gets better at automatically manipulating them, that challenge is only going to become a lot more intense over the next few years.

"Can I do this myself?"

That doesn't mean that people won't still need working photographers, of course. But the question is: will they need them so much? For example, I know people at creative agencies who once routinely hired commercial photographers for every job. But nowadays they admit (anonymously, and in private) they're now stopping to think: 'Could we just take these shots ourselves?'

It's not even always a budget issue; it's often just a hassle issue. No one likes paperwork. And the fewer invoices they have to generate, briefs they have to write, and lengthy email chains they have to wade through, the better.

Also, when clients do hire photographers, I'm hearing that the rise of powerful smartphones is shifting those clients' expectations.

Given that their own phone cameras allow them to instantly capture, edit, and share high-quality images, they've grown accustomed to rapid visual gratification. And so where once it was standard to wait days or even weeks for processed images, there's now an increasing demand for same-day or even on-the-spot delivery of finalized photos.

Indeed, the expectation for rapid results extends beyond just delivery times, encompassing the entire photoshoot experience. Clients often anticipate seeing preliminary edits or selections during or immediately after a shoot, mirroring the instant feedback loop they're used to with smartphone photography.

This pressure means photographers will be increasingly challenged to streamline their workflows, and adopt real-time editing and preview techniques. Either that, or get better at managing expectations and explaining why it's better to wait for a job well done.

All of this is achievable, of course. And all of this has happened before, every time camera technology has taken a new leap forward. But it's also stuff we need to be thinking about, lest the world suddenly leaves us behind and we sit there wondering: "What happened?"

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.