Oh India: Australian photographer Thomas Parrish talks about his new book

Photojournalist Thomas James Parrish talks about a charity project in West Bengal that’s become a big part of his life

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Right from the time cameras could be taken into the field, photography has been used to highlight issues and instigate change. The power of a descriptive still image remains undiminished even in this era of widespread video usage, and many photographers dedicate themselves to using the medium as a catalyst for people taking action.

Sydney-based photojournalist and travel photographer Thomas James Parrish is one of these, driven by a passion for exposing and championing both environmental and humanitarian issues. Working closely with local NGOs, charities and communities, this passion has taken him across the world, founding projects and campaigns with refugees, environmental agencies, religious groups, and education programs.

“With my work, I try to emphasize our responsibility as humans to care for the world, and to express the importance of compassion and identity through engaging storytelling. I hope I ensure a positive impact on humanity and the natural world and that my photographs can act as an instrument for inspiration and change.”

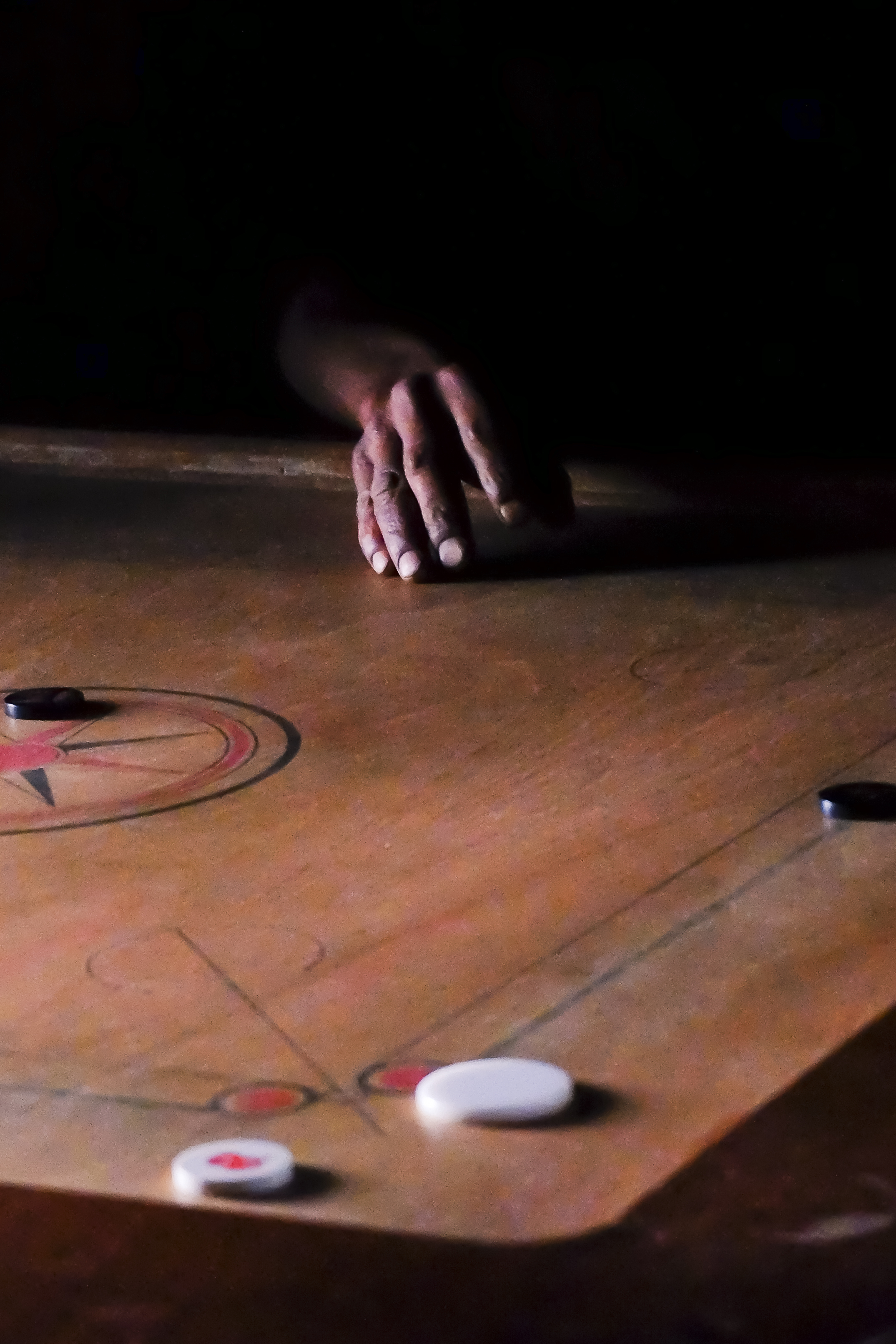

Thomas’s latest project is a photobook titled "Oh India" that he’s produced to help raise funds for a village in India’s West Bengal region that was first hit by the Covid-19 virus and then devastated by a cyclone that destroyed houses, invaluable crops, and vital agricultural resources.

Thomas explains why this particular village in India has become so important to him.

“I was sitting in a tiny café in Darjeeling, in north-east India, when I overheard an Australian accent talking about the Blue Mountains – my favorite place in Australia – to the waitress. I struck up a conversation and it turned out that he lived just down the road from me, so we started chatting about what each of us were doing in India. His name is Michael Symonds, who founded a charity group called Cobra and Mongoose that supports local grass-roots programs across Asia and Africa. His ethos is to facilitate inclusive local projects without the overreaching hand of white saviorism... in other words, let the locals do the work, and let the locals be the difference. He raises money for projects he believes in, from schools to homeless centers, and gets them off the ground, dealing primarily with the orchestrators of the projects. He keeps himself removed from the beneficiaries so they can maintain inspiration for the members of their community who are making a difference.

“I told him how I wanted to see the real India and he told me that I should visit an education program called Kaikala Chetana which is about 50km from Kolkata. So a week later, I was met at the train station by two volunteers from the program who bought me a ticket, fussed that I should take the last seat on the train, and took me to Kaikala. There I met Somanth who was a local man who gave up his city job to turn his village home into an education center so that he could provide free education to the village children who would otherwise go without.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

“That was in 1996, and the program now offers free education to over 800 children across over 20 locations. I loved it. I have kept in contact with Somnath ever since. When Covid hit and then the severe cyclone, Somnath spearheaded the recovery operations for the village, funneling money from the education program into other important areas for the village's recovery. So, I put together the Oh India photobook to support Somnath and his mission to restore the village and maintain the education program. So far we’ve raised enough money to fund the program for two years.”

Sharing A Story

Thomas’s interest in photography came from his father who traveled extensively in the late ‘70s and throughout the ’80s, taking photographs wherever he went.

“I grew up with his incredible images of distant lands which also inspired me to travel. He taught me all about shutter speeds, apertures and ISO setting before getting me a digital camera for my 21st birthday. A year later, I traveled to India to put his teachings to the test, following in his footsteps from his travels across the country some 40 years earlier. I just fell in love with photography’s ability to break down the barrier between me and strangers. I dug so much deeper into traveling than I otherwise might have to get interesting images. That feeling of witnessing, capturing, and sharing has excited me ever since.”

At the same time, Thomas also realized photography’s potential for raising awareness about the issues that were important to him.

“Photography, for me, will always be about having something to say, sharing a story, and giving a voice. I care greatly about humanitarian and environmental issues, and photography allows me to not only explore these themes in great depth, but share their importance and even raise money for causes I believe in. I’m passionate about inspiring positive social change and photography offers me a medium through which to do so. I’ve met some exceptional people thanks to photography.”

Perhaps not surprisingly then, Thomas doesn’t need a lot of motivation when it comes getting behind the camera and pursuing a picture... and he doesn’t mind a pre-dawn start either…

“It’s easy to get bogged down when the commissions and features aren’t coming in, but when I’m thinking about the way my photography can help others, that’s what really motivates me and keeps me going.

“If I’m traveling, I’m always up before dawn because the light is at its most beautiful and the atmosphere is always the most serene in the early morning.”

In The Firing Line

Thomas names a number of photographers who have helped influence his work, including the Greek-born British portrait and documentary photographer Platon, and the American documentary photographer Alec Soth who is particularly known for his large-scale projects, some of which are made using an 8x10-inch view camera.

“Platon’s ability to disarm his subjects to ensure he captures them as their most authentic self is incredible; he’s a big inspiration for me when it comes to connecting with people. Alec Soth’s patience with long-term documentary projects is incredible, as is his mastery of large-format film cameras.

“Overall though, my favorite photographers are those that put themselves in the firing line to share stories that have the power to make a difference. Paul Hilton’s work in the exotic wildlife trade and Jo-Anne

McArthur’s work in animal agriculture and abattoirs must be so hard to face, but they do it because they know that whatever they are experiencing, it’s nothing in comparison to the experience of those they are photographing. That philosophy of photographing for something bigger than themselves at the potential expense of their own wellbeing really pushes the boundaries of what is possible for a photographer and is heartbreakingly inspiring.”

Despite the fact that we’re now bombarded daily with imagery from all sources, particularly social media, Thomas believes documentary photography still has the ability to tell powerful stories with the potential to change perceptions or policies.

“Absolutely, I truly do believe it does. Sometimes I question whether or not it seeps through the cracks of the meaningless content that Instagram produces, but I still wholeheartedly believe in the power of meaningful photography and its ability to influence and make a difference, because I’ve seen it, and it’s something that I’ll continue to strive to achieve.”

Respect And Understanding

Some documentary photographers prefer to take the role of an observer, but others like to be more involved with their subjects. Thomas Parrish says that he uses both approaches, depending on the situation.

“Portraiture is my favorite form of photography, and I feel the best portraits are produced when there is a mutual respect and understanding between photographer and subject... and that can only happen through connection. So, more and more I want to get as involved with my subjects so that I can understand them, empathize with them, and above all, care about them. The observer role is a necessary one when I’m in the street – maybe at a protest or an event – but the editing process feels far more detached, and I think connection is what I’m really looking for through photography.”

Despite having started his photography with a digital camera, Thomas has since also taken to shooting with film, using a Mamiya TLR which he feels enhances the sense of involvement for both him and his portrait subjects.

“I use both digital and analog cameras depending on the project. My India work was all done on a Fujifilm X30, the camera my dad bought me for my 21st birthday. I loved it for its compactness and ease of use, and sometimes I’m still amazed at the photos I made with it. Now I’ve moved on to a Sony full-frame mirrorless camera – the colors and definition are just breathtaking, and the sophistication of its features gives me so much control and I enjoy that. I use a Mamiya C330 for a lot of my portrait work. I love the time it takes to set up a shot, the care I need to take as to not waste the film, and the curiosity it inspires in my subjects, getting them excited about the photographic process.”

Post-camera editing is now rife in photography, but does it have any place in documentary photography? For example, is it okay to enhance an image if it tells a better story? Thomas contends there’s an argument for enhancing the impact of an image.

“I think it’s important to utilize the progression of technology, and post-production is a vital tool in making sure your photos are as good as they can possibly be. We see so much content on news feeds that powerful photography is at risk of being missed in the midst of avo toasts and cat videos, you have to make your image stand out and catch people’s eye. You’ve still got to capture a great image in its raw form though, and no amount of editing can make a shit photo any good. I’m not one for superimposing things that were never there, but I’m definitely one for making an image really pop. Go easy on the clarity slider though.”

Intense Simplicity

Above all his other objectives, Thomas says the thing he loves most about photography is how it puts him unambiguously ‘in the moment’.

“Photography plants me in the present. When I’m looking through the lens at someone who’s just told me their story or observing something I’ve never seen before, the whole world slips away and I’m caught in this moment of intense simplicity. Nothing else matters except nailing that exposure, understanding the light, and composing that frame. I love that simplicity. It’s a notion that is lost in my life everywhere else as I overthink and overanalyze things. When I’m photographing and telling a story, I know I’m on the right path and I hope my photographs can act as an instrument for positive social change.”

If you would like to buy a copy of Oh India, go to Thomas James Parrish's webstore, worldwide shipping is available.

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.