Medium format film cameras: a complete history

If you are thinking of buying a secondhand film camera, why not get a big one? These are your roll-film options…

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When I last wrote about at the options for shooting with medium format film cameras back in 2016, there was a bit of a question mark over the continued availability of rollfilm. It certainly tempered any enthusiasm for spending a reasonable amount of money on, say, a classic Hasselblad. While the choice of rollfilm stocks is certainly a lot smaller than it was when medium format was the choice of manyprofessional photographers, the old favourites are still available in B&W, colour negative and colour transparency. And there' seemingly enough interest to keep this going. For anybody contemplating getting into (or getting back into) film photography, 35mm looks like the obvious choice as there is a huge selection of cameras to choose from, either second hand if you want an SLR or a rangefinder type, or new if you want something a bit quirky. But medium format adds a bit more to the experience with the handling of rollfilm and the camera operations, particularly with boxform cameras. There is also quite a variety of cameras from SLRs to fixed-lens rangefinder types, and not all are fully manual, mechanical machines as, latterly, automation did find its way into the medium format camera world. However, don’t expect the point-and-shoot convenience of a digital camera.

Most medium format film cameras will make you work – some harder than others – but that’s part of the attraction. So is the size. Even the non-reflex designs are still pretty chunky, but something like the Mamiya RB67 is a beast – big, heavy and very noisy.

Rolling up

Rollfilm was responsible for popularizing photography at the end of the 19th century and, over time, there have been numerous formats with 120 slowly becoming the standard (although it dates back to 1901). Today, 120 is the sole survivor and this overview concentrates on cameras for this film size… which are all higher-end models from after the Second World War.

As the name suggests, rollfilm is a roll of film that is wound into a spool along with a backing paper. There is no light-tight cassette, but the backing paper ensures that the film can be taken out of its packaging in daylight without fogging the edges. Nevertheless, it was still always advised to load the camera in subdued lighting and certainly not in direct sunlight. Loading involves feeding the film’s leader paper onto an empty take-up spool – which would have been the loaded spool from the previous film, swapped into the take-up position when it was finished – then winding on a little, closing the camera back and completing wind-on to the first frame. Once the roll is completed, there’s no need for rewinding as all the exposed film is now on the take-up spool, ready to be removed from the camera and processed. To ensure it remains tightly rolled up – to avoid any fogging – a sticky tag is provided to secure the end paper. In the day, many amateurs were put off using medium format cameras because it was perceived that loading and handling rollfilm was tricky and it was too easy to make a mistake. In reality, it’s all fairly straightforward and it only takes a couple of loads before it becomes second nature. A few medium format cameras do have certain loading idiosyncrasies, so it isn’t always a straight thread from the feed spool to the take-up spool, but in most cases it’s pretty easy to work out the procedure.

The key thing to remember is that rollfilm is essentially ‘naked’ when it’s out of the packaging and out of the camera, so it needs to be handled accordingly with regard to any exposure to bright light.

120 rollfilm is 61mm in width, which dictates the designation of the various formats or, more specifically, image sizes. The classic format is 6x6cm, which was once more commonly called “two-and-a-quarter square” based on the frame’s dimensions in inches. Six-by-six was the most popular medium format image size for a long time as it allowed for many cropping options when shooting with cameras that weren’t practical to use in the vertical or portrait orientation… such as the twin lens reflex (TLR). However, various rectangular frame sizes became available over time, most notably 6x7cm and 6x9cm for a larger image area, and 6x4.5cm for a smaller one. With the 6x4.5cm format, the frame is on its side – i.e. in the vertical orientation – so these cameras are held vertically if you want the landscape framing. The attractions of 6x4.5cm are more compact cameras and lenses, and up to 15 frames from a roll of 120 film versus 12 with 6x6cm and just 10 with 6x7cm.

In 1965, a double-length 220 roll film was introduced using exactly the same spool as 120. The extra length was accommodated on the spool by using backing paper at only the start and finish of the film, but this meant the film pressure plate in the camera needed adjustment as the film by itself was thinner than when there was both film and backing paper in the gate. Subsequently, compatible cameras had 120/220 settings on the film pressure plate that adjusted the tensioning springs. 220 obviously reduced the number of times film needed to be changed during a shoot and demand was mostly driven by pros. It’s no longer available in any of the ‘mainstream’ stocks, but CineStill has plans to launch an ISO 400 color negative film in 220 rolls by the end of 2022, and there may be others down the track.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

What roll-film camera?

Now that we’ve demystified using 120 rollfilm and the availability is better than it’s been for a long time, what should you think about putting it in? A potted history of the development of medium format cameras designed primarily for professional use will help set the scene as it’s primarily these models – and their derivatives – that have the most potential for use today in terms of both reliability and operational ease.

In the days when there was a clear distinction between the studio camera and the field camera, the evolution of the latter was driven by improving portability and speed. So the large format Speed Graphic – beloved of press photographers from the 1920s to the 1950s – gave way to the twin lens reflex and 120 rollfilm. The TLR dominated through the 1950s and early 1960s as it was widely used by both amateurs and professionals. The Rolleiflexes in their many guises are the best known today, but for a while just about every camera maker of note offered a TLR. It allowed for reflex viewing, but by using a separate lens for this – matched with the taking lens – it was a simple and rugged design that was also quiet in its operation.

With the arrival of box-form SLRs, as pioneered by Hasselblad in 1948, the TLR soon fell out of favour among professionals, but their simplicity made them comparatively inexpensive to manufacture and extremely reliable. Consequently, they represent an affordable entry point to medium format film photography with only the rarer Rolleiflexes being really expensive, along with the largely hand-built last-of-the-line models.

Mamiya And Rolleiflex TLRs

The majority of TLRs have fixed lenses, but Mamiya developed an interchangeable lens arrangement and the last-of-the-line C330 Professional S remained in production until 1994. Aside from built-in metering in some models, TLRs are fully mechanical and, given the fixed reflex mirror for

Most medium format film cameras will make you work – some harder than others – but that’s part of the attraction.

The manufacture of Rolleiflex TLRs spanned over 80 years and didn’t cease completely until late 2014, although volume production ended in 1979. This run included the more amateur-orientated Rolleicords, which were built in large numbers and are consequently also a cheaper option today. Japanese camera-maker Yashica also persisted with the TLR for a long time and was still making the Mat-124G in the mid-1980s, which means these are still comparatively new classics.

The majority of TLRs have fixed lenses and mostly with the standard focal length (on the 6x6cm format) of 75mm or 80mm, but the notable exception is Mamiya which, in 1956, introduced the first model with interchangeable taking/viewing lens sets. There was eventually a choice of seven focal lengths from a 55mm wide-angle (equivalent to 30mm) to a 250mm telephoto (137mm), and the cameras – the C3 series and the lower-priced C2 series – remained in production until 1995. For obvious reasons, the Mamiya C series cameras – especially the last C220 and C330 models – are a good buy today, but prices are on the rise and some lenses are becoming harder to find.

Hasselblad 6x6cm

The ability to swap lenses was the main impetus behind the development of the box-form medium format SLR and Hasselblad took the opportunity to make its design fully modular, so film magazines and viewfinders could be swapped too. This configuration was subsequently emulated by Bronica and Mamiya, and simply copied by the Russians with the Kiev 88.

The original Hasselblad 1600F was plagued with shutter-related problems as nobody had tried to make such a large focal plane mechanism operate at a top speed of 1/1600 second before. Eventually Hasselblad gave up trying to make it work reliably and switched to in-lens leaf shutters, giving birth to the legendary 500 series. The original 500C was launched in 1957 (the ‘C’ stands for Compur which supplied the shutters, and ‘500’ represents the top speed of 1/500 second) and the same basic configuration – with fully mechanical operation – was retained for 56 years. There were many small advances along the way, making the later models more desirable for today’s user, although the 500C/M – which was introduced in 1970 – is quite easy to work with and, in fact, stayed in production until 1994 (including a brief period when it was called the 500 Classic). The subsequent models – 501C, 501CM, 503CX, 503CXi and 503CW – all retain the traditional Hasselblad 6x6cm SLR attributes and, as such, deliver a true classic medium format film camera experience.

In 1965, Hasselblad introduced a motorised version of the 500 called the 500 EL and, once again, the later versions are more desirable, even though the various updates or revisions were usually minor. Look for the 500 EL/M (1970-84) or later models such as the 500 ELX and 553 ELX. Also check that the EL/M model you have your eye on has been converted from the proprietary NiCd batteries to run on standard AA size cells.

In 1977, Hasselblad returned to using a focal plane shutter with its 2000 series of 6x6cm SLRs and, later, the 200 series, but these have never been as popular as the 500s. Check shutter accuracy and reliability if considering an early 2000 series model such as the 2000 FC or FC/M.

Perhaps the quirkiest of the classic Hasselblads are the Superwide (SW) models that eliminated the mirror box and focusing screen. They have a fixed Zeiss Biogon 38mm f4.5 ultra-wide lens with a non-coupled optical viewfinder. This makes them a lot more compact than the standard cameras and very easy to use handheld. All the SW models – later called SWC – accept the standard Hasselblad 120/220 rollfilm magazines. The optical performance of the 38mm Biogon lens (equivalent to a 21mm in 35mm format terms) is legendary, but the later versions benefit from improvements to multi-coating technologies to enhance contrast and colour. Consequently, the 903 SWC (1988-2001) and 905 SWC (2001-2006) are very highly sought after – especially by landscape photographers – and now sell for a lot more than their original price.

Mamiya 6x7cm & 6x4.5cm

With the 6x6cm format covered by its TLRs, Mamiya adopted the modular medium format SLR design for 6x7cm first in 1970 with the RB67 Professional and then, in 1975, 6x4.5cm for the more compact M645.

Like the 500 series ’Blads, the RB67 is fully modular, but with film holders that rotate on the camera back to conveniently switch between the landscape and portrait orientations. The RB-mount lenses incorporate Seiko leaf shutters and the range eventually included over 20 models, from a fish-eye to a telephoto.

The RB67 Pro S model was launched in 1974 along with new K-series lenses and, in 1990, the Pro SD which could be fitted with a 6x8cm format film magazine. It’s the pick of the litter if only by virtue of being younger, but all RB67s were built tough and the overall reliability is generally good. As noted earlier, however, these are big and heavy cameras and, in practice, not all that comfortable to use handheld.

Likewise, the RZ67, which was introduced in 1982 and retained the RB’s revolving film backs and bellows-type focusing. However, the RZ lenses incorporated an electronically controlled Seiko leaf shutter, LED displays and provision for aperture-priority auto exposure control when fitted with the AE prism finder. Of course, this meant it was dependent on battery power that the more traditionalist pros considered a drawback. They were also sceptical about the polycarbonate (rather than metal) bodyshell, so the RZ67 didn't quite gain the same popularity as the camera it was meant to replace.

Consequently, the RB67 stayed in production alongside the RZ67. The latter was subsequently updated to the RZ67 II in 1995 and RZ67 IID in 2004 – the IID equipped to better integrate with digital capture backs. RB lenses can be used on the RZs – albeit with the loss of auto exposure control – but RZ lenses don’t fit the RB bodies. Ironically, you’ll probably pay less now for an RZ67 than an RB, although the former didn’t prove to have any reliability problems.

In contrast to the 6x7cm format Mamiya SLRs, the 6x4.5cm models are comparatively compact and the original M645 is a pretty thing too. To help make it smaller and also reduce cost, the M645 doesn’t have interchangeable film magazines, but the finders can be swapped and, of course, the lenses. There were three first-generation models – the standard camera being flanked by the M645 1000S with a faster 1/1000 second shutter and additional features (including a self-timer) and, in reverse, the stripped-down M645J designed as an entry-level model.

A completely new camera, called the M645 Super, was introduced in late 1985 with a polycarbonate bodyshell and interchangeable film magazines, plus a host of convenience features to bring its operation more into line with that of the 35mm SLRs from the period. This included the option of adding an autowinder housed in a handgrip.

Subsequent models were the 645 Pro (1992, and the ‘M’ prefix was dropped), the 645 Pro TL (1997) and the 645E (2000, with a fixed prism-type viewfinder). At roughly the same time as the 645E, Mamiya launched the 645AF, again with an all-new bodyshell and, of course, autofocusing. The 645AF then spawned the 645AFD, 645AFD II, 645AFD III, 645DF and 645DF+ with the latter three also being marketed as Phase One models. However, the DF and DF+ can’t be fitted with film backs.

Bronica, Contax, Hasselblad & Pentax 6x4.5cm

The 6x4.5cm format enjoyed growing popularity during the 1980s and ’90s, primarily because it combined a more compact camera body (and lenses) with an image size that’s still 2.7x bigger than 35mm. As already noted, it also gives 15 (or maybe 16) frames per roll.

Bronica, Hasselblad and Pentax also offered 6x4.5cm SLRs alongside Mamiya, and Fujifilm built a number of 6x4.5cm rangefinder models with fixed lenses that offered an even more appealing balance of camera size and image size (more about them shortly).

Bronica’s ETR series of 6x4.5cm SLRs never quite achieved the popularity of Mamiya’s M645 cameras, but they were preferred for wedding photography and portraiture as they used leaf-type shutters (enabling flash sync at all speeds) and interchangeable film magazines right from the start. Bronica also competed in the 6x7cm format with the GS-1 launched in 1983, but again never challenged the dominance of the Mamiya RB67. Nevertheless, it’s a fine camera – if you can track one down – and backed by a reasonable system of leaf-shutter prime lenses.

Pentax’s original 645 model – launched in 1984 – was revolutionary at the time, bringing all the features of a contemporary 35mm SLR to a 6x4.5cm format model, including TTL centre-weighted metering, a full set of PASM exposure control modes, a built-in autowinder and an LCD info display. And it was backed by an extensive system of lenses. The 645 evolved into the 645N (1997) which introduced autofocusing and multi-zone metering – both firsts for medium format SLRs – and increased the autowinder’s speed from 1.5fps to 2.0fps. The 645N II followed in 2001, adding several new features including a mirror lock-up. Some lenses are still available new to support the digital Pentax 645Z.

Most discussions about classic Hasselblads concentrate on the 500 series models but, at the 2002 Photokina, the Swedish camera maker made an announcement that was almost as momentous as the historic 1948 press conference. With the launch of the H1, Hasselblad introduced an all-new system based on the 6x4.5cm format – it was co-developed with Fujifilm who made the H-mount lenses (and still do). There was no compatibility with the 6x6cm cameras – then renamed the V System – but the H System looked forward to the digital era. Nevertheless, the H1 was resolutely a film camera and still offers the Hasselblad medium format experience, albeit with a lot more mod cons, including autofocusing and motorised film advance.

Today, the H1 is definitely worth considering for anybody serious about shooting rollfilm and, given its more contemporary design, it’s much less of a culture shock than the mechanical models. Prices are reasonable in comparison too, but the lenses are expensive as this is still a current system, so second-hand examples tend to get quickly snapped up by working pros. Remember too, that body-only prices don’t tend to include a film magazine, so you’ll need to budget for this.

The H2 was introduced in 2006 and is the same camera physically, but was designed to better integrate with a digital back. It accepts a film magazine and body prices are pretty similar to those of the H1, so you don’t necessarily have to hang out for the earlier model. Depending on your budget and commitment, you might also consider the later H2F and H4X models, but beyond the H3DII most of the H System bodies – the current series is H6 – are exclusively for digital capture.

Perhaps even more exclusive than the H1 is the Contax 645. Having built up a solid reputation with the 35mm RTS series SLRs, in the late 1990s parent company Kyocera decided it was time to move into the big league. The 645 boasted the same build quality as the RTS bodies and the autofocus lenses were made by Zeiss. Film backs and viewfinders are interchangeable and the film transport is motorized. The film pressure plate uses a vacuum suction system to ensure the film is completely flat in the gate, thereby making the most of the optical performance of the lenses. The focal plane shutter has a top speed of 1/4000 second.

The Contax 645 was highly desirable when it was launched in 1998 and still is today. Consequently, prices remain very high – in fact, far exceeding those of the Hasselblad H1 or H2 – so you’ll probably need to really want the Contax marque to make this sort of investment. And bear in mind with Contax also long defunct, if something goes wrong, you’ll be looking at buying another body for your lenses. The good news is that there appear to be no serious issues, but this is still a purchase that needs to be very carefully considered in the light of the less risky alternatives.

Pentax 6x7

The modular box-form camera dominates the medium format film camera world, but there is one notable exception. Pentax’s 6x7 was launched in 1969 and bucked the design trend by being styled like an over-sized 35mm SLR. It wasn’t unique as the East German Pentacon Six – which was similar in configuration – had been launched earlier in 1966, but the Pentax was, of course, a Pentax and made in Japan, so it wasn’t facing much competition, at least as far as professionals were concerned. And, obviously, it was a 6x7cm format camera, not 6x6cm.

The body design greatly enhanced the handling and made the 6x7 easier and more comfortable to use handheld… as did a substantial wooden handgrip. Viewfinders can be swapped (including a metering prism), but the film transport is integrated with a conventional hinged camera back.

Although, the 6x7 is a fully manual camera, it still requires a battery to actuate the focal plane shutter. It has a top speed of 1/1000 second, but the limitation for some professional photographers at the time – such as those in the wedding business – was the maximum flash sync speed of only 1/30 second. Subsequent models were the 67 (1989), which introduced a range of ergonomic improvements, and the 67 II (1998) with a built-in handgrip and LCD info panel. The AE prism finder introduced for the 67 II added six-zone matrix metering and the option of aperture-priority exposure control.

Particularly noteworthy is the very extensive system of lenses – in medium format system terms – which included leaf-shutter types, a fish-eye, a mirror-type supertelephoto and a shift lens. The original Asahi Pentax 6x7 is a rugged and reliable camera, and although the earliest models did have film transport issues, these would all have been repaired and upgraded at the time. Arguably then, a nice 6x7 is the best option if you like the idea of that big and airy 6x7cm frame. There are plenty available on the second-hand market and you get a lot of camera for your money. With a few more electronics, the 67 II in particular could present problems with repair if one of these components fails. Regardless of the variant, definitely look at one in the flesh before buying… they’re very much bigger in reality than any illustration suggests.

The other camera worth mentioning in this context is the Norita 66 which was launched in 1971. Again, it’s 6x6cm in format, but it was Japanese-made and backed by a reasonably large lens system. However, it wasn’t in production for very long (finishing in 1976) and so is a bit rarer than the Pentax, but still not overly hard to find.

The Pentacon Six was sold in Australia as the Hanimex Praktica 66 – grab one if you see one as they’re very rare – and in the West as the Exakta 66, which was built in West Germany. If you’re feeling really courageous, there’s also the Russian-made Kiev 60 – essentially a copy of the Pentacon Six – but, with the exception of the Norita, all these cameras are probably more curiosities or collectibles than something you’d contemplate using on a regular basis.

The other Rolleiflexes

There were medium-format Rolleiflex cameras that weren’t TLRs. The 6x6cm SLR models are much less well-known than the twins, but with them, Rollei set out to take on Hasselblad and even beat it for reliability and durability.

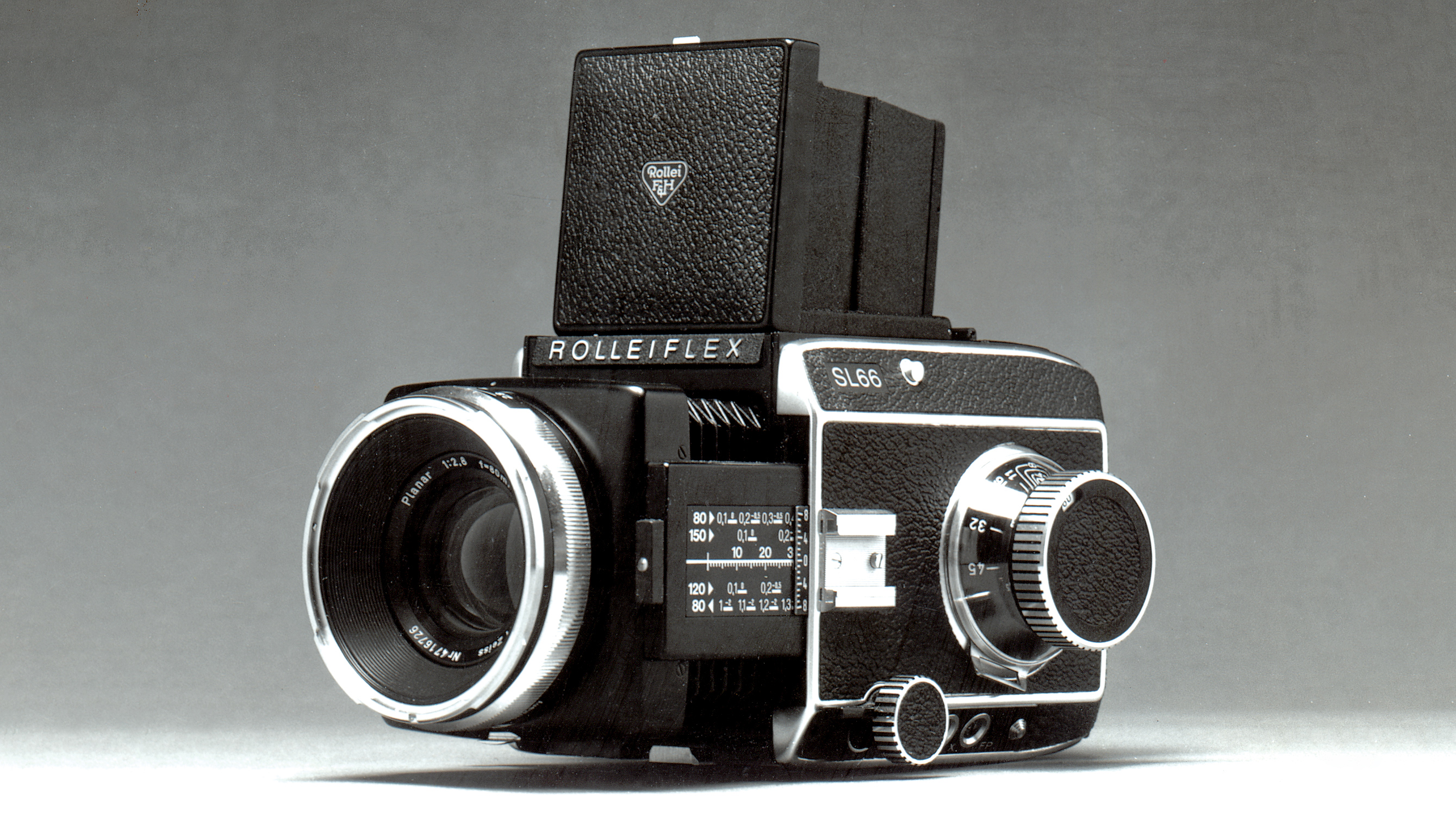

The SL66 was introduced in 1966 and shared the same basic configuration as the 500 series Hasselblads, but had bellows-based focusing with tilt movements for greater control over depth-of-field. However, these cameras were built in very small numbers compared to the Hasselblads and, consequently, are both much harder to find and much more expensive

In 1976, Rollei revolutionized medium format film camera design with the SLX which offered the conveniences of a built-in autowinder, TTL metering, shutter-priority auto exposure control and LED indicators in the viewfinder. It was way ahead of its time. The SLX evolved into the 6006 (1983), which added the flexibility of interchangeable film magazines – with ingenious built-in ‘roller blind’ dark slides – and features such as off-the-film (OTF) auto flash metering. The 6000 range ultimately culminated in the 6008AF (2002) which, as well as autofocusing, has multi-zone metering, PASM exposure control modes, auto bracketing, a full LCD viewfinder display and continuous shooting at up to 2fps.

The 6008AF was always been a rare beast even when it was current (likewise the Schneider-made AF lenses) and is even more so now. Be prepared to pay a lot if you really want one with a workable set of lenses. In fact, rarity means any Rolleiflex 6x6cm SLR carries a premium on pricing.

Fujifilm rangefinder cameras

The more affordable route into medium format photography was traditionally via a rangefinder (RF) camera, but this isn’t necessarily true today as the combination of portability and image size has pushed up values, especially of models with interchangeable lenses. The more recent reality that rollfilm isn’t about to disappear has also buoyed the market.

However, still likely to be comparatively affordable is Fujifilm’s line-up of fixed-lens medium format RF cameras, which were under-appreciated even when they were new. Incidentally, Fujifilm initially offered a choice of interchangeable lens models (badged Fujica) in the 6x7cm and 6x9cm formats. These early models are now very rare and highly collectible so, if affordability is your priority, it’s the fixed-lens model from 1978 onward that are worth considering.

These start with the GW690 and the GW670 fitted with a 90mm f/3.5 lens, which was equivalent in focal length to a 35mm on the 6x9cm GW690 and a 42mm on the 6x7cm GW670. Fujifilm introduced the GSW690 in 1980 which had a fixed 65mm f/5.6 lens, equivalent to a 25mm in the 35mm format. Series II versions of all three models arrived in 1985 and the main changes were the addition of a hotshoe (rather than just a ‘cold’ mount) and a built-in lens hood, plus the Fujica name was dropped in favour of simply “Fuji”. The Series III cameras were launched in 1992 and featured radically restyled bodyshells and a redesigned viewfinder that has a brighter, Leica-style rectangular double-image rangefinder rather than the previous spot.

Perhaps the most interesting models, though, are the 6x4.5cm cameras which are exceptionally compact, but deliver the image quality benefits of the bigger frame size. The Fujica GS645 Professional was essentially a modern interpretation of the old 6x6cm ‘folder’, complete with a 75mm f/3.4 lens (equivalent to 45mm) mounted on bellows so it could be retracted into the camera body, making for an even more compact package. There was also a GS645S model with a rigidly-mounted 60mm lens (equivalent to 35mm) and a GS645W with a 45mm lens (equivalent to 28mm). Both these cameras have a distinctive curved ‘bumper bar’ arrangement to protect the front rim of the lens. All the GS645 models have built-in metering which is something that was never available on the 6x7cm and 6x9cm cameras.

The later-generation GA series models, introduced in 1995, were essential medium format versions of a point-and-shoot 35mm compact with autofocus, programmed exposure control, motorised film advance and a built-in, pop-up flash. However, fully manual control is also available. As with the previous series, Fujifilm subsequently introduced a wider-angle version, called the GA645W and fitted with a 45mm f/4.0 lens (equivalent to 28mm). Both were subsequently upgraded in 1997 as the GA645i and GA645Wi, with the main change being the addition of a second shutter release button on the front panel. In 1998, Fujifilm introduced the last-of-the-line GA645Zi model, which has a 55-90mm f/4.5-6.9 zoom lens (equivalent to 35-55mm) and a restyled body with a more pronounced handgrip.

None of the Fujifilm medium format fixed-lens cameras were built in big numbers, but most are fairly easy to find second hand and are generally reasonably priced too. Our picks would be the GS645W for the purist approach or the GA645W if you’d prefer more automation. And the GA645Zi is just a hoot.

Fuji medium format SLRs

Fujifilm also dared to be different when it finally ventured into the medium format SLR market in 1989 with the GX680 Professional. It was a 6x8cm format model, and borrowed an aspect-of-view camera design so the lens mount ran on twin rails and was connected to the body via bellows. This allowed the lens standard to be tilted for depth-of-field control and shifted for perspective control, and the range of both was quite extensive.

As on the Mamiya RB/RZ, the film magazines rotated to switch between landscape and portrait framing, and there was a choice of waist-level and eye-level viewfinders, including an AE version of the latter for aperture-priority exposure control.

There was eventually a system of 18 lenses, so the GX680 was a hugely capable professional tool, although not surprisingly, it’s a bulky beast and rivals the Mamiyas for its physical presence. There were Mark II (1995) and Mark III (1998) versions, although the upgrades were mostly minor so any model is worth considering today if, ahem, you’re thinking outside the square. Bear in mind, it was primarily designed for studio use and so works most comfortably when mounted on a tripod. All the versions were only built in small numbers, but they’re not all that hard to source on the second-hand market and, at the moment at least, surprisingly well priced. The size, weight and perceived complexity of the bellows system probably put quite a few people off, but they’re worth considering you’re really up for a challenge.

As noted earlier, the 6x4.5cm Hasselblad H1 was co-developed with Fujifilm and the agreement allowed the latter to market the camera under its own branding in Japan. The Fujifilm GX645AF is identical to the H1 – although there are some cosmetic differences – so all the lenses and accessories are the same. A few of the Fujifilm models found their way onto the Australian market and are interesting by virtue of rarity, but if you see a good H1 for less money…

Incidentally, Fujifilm didn’t continue with the range when Hasselblad introduced the H2.

Bronica And Mamiya rangefinder cameras

Just as in the 35mm format, the interchangeable lens rangefinder camera enjoyed a curious final fling in the medium formats before digital put an end to it all. You can have them in all the popular film sizes – 6x4.5cm with the Bronica 645RF, 6x6cm with the Mamiya 6 and 6x7cm with the Mamiya 7. All were comparatively short-lived so the choice of lenses for each is small, but still provide greater versatility than the fixed lens models from Fujifilm.

A bit of a surprise when it arrived in 2000, the Bronica 645RF was pretty much the brand’s last roll of the dice, and it’s a thoroughly modern design with fully electronic controls, including program and aperture-priority exposure modes and automatic parallax correction in the viewfinder. It was launched with three leaf-shutter lenses – a 45mm f/4.0 (34mm equivalent), a 65mm f/4.0 (40mm) and a 135mm f/4.5 (100mm) which was quickly replaced by a 100mm (75mm), but both these short telephotos are extremely hard, if not impossible, to find.

With Bronica long gone, spare parts and repairs are now a major issue, which is why it might be wiser to consider the Mamiyas as they were made in greater numbers. Introduced in 1989, the Mamiya 6 – the last in a long line of cameras to have this model number – is a more traditional design than the Bronica and, of course, offers the flexibility of the square format. Also more useful is the lens line-up although, again, there’s only three models – a 50mm f/4.0 (28mm equivalent), 75mm f/3.5 (45mm) and 150mm f/4.5 (82mm) – all with electronic leaf shutters. A collapsible lens mount makes the 6 more compact to store, and it has modern ‘conveniences’ such as aperture-priority auto exposure control, auto frame selection in the viewfinder and single-stroke film advance.

The Mamiya 7 (1995) is essentially the same camera in terms of design and features, but steps up to the 6x7cm format – which is 4.5x larger than 35mm – so it’s bigger and there’s a choice of six prime lenses from a 43mm f/4.5 ultra-wide (21mm equivalent) to a 210mm f/8.0 telephoto (105mm). An updated model – the 7 II – was introduced in 1999 and has an improved viewfinder, a few ergonomic revisions and a multiple exposure capability. In practical terms, the changes between the two models are minor so don’t be put off from buying the Mark I model. A key advantage of all the medium format RF cameras – versus some SLRs – is that loading the rollfilm is a simple right-to-left (or vice versa) procedure and so virtually no more involved than using 35mm… but, of course, you don’t need to rewind at the end.

Conclusion

Using any medium format film camera is guaranteed to be an experience, but depending on the vintage and configuration, some certainly demand more from you than others. Consequently, you need to decide whether you just want to have a bit of fun or whether you want something to use for more serious photography, leveraging the increased quality of the larger frame sizes versus 35mm.

There are a few good reasons for going down the mechanical camera route, not the least being the inherent reliability of a more basic design. While it may seem re-assuring to opt for a more automated camera, you’ll be surprised how quickly and easily you can become accustomed to doing everything manually… and it’s generally a whole lot more fulfilling. Given the vast majority of medium format film cameras were designed and built with professional usage in mind, reliability is generally less of a problem than might be the case with amateur cameras of a similar vintage, but the simple truth is that there’s less to go wrong with an all-mechanical design versus one that employs some electronics and, in particular, is fully dependent on battery power.

The choice here, then, is extensive and includes Hasselblad’s 500 series cameras, the mighty Mamiya RB67 and the first M645 models, all TLRs, Fujifilm’s earlier rangefinder designs and the Rollei SL66s (with the caveats mentioned earlier). Nevertheless, there are battery-dependent cameras worth considering such as the Pentax 6x7 and 645, and you could safely ‘go all the way’ with something like the Fujifilm’s autofocus GA series which are great fun to use. If you want to travel light – well, lighter – a medium format rangefinder camera of any flavour makes sense, but obviously the interchangeable lens modes offer more flexibility. Consequently, both the Mamiya 6 and 7 are continually in demand and the Bronica RF645 has maintained high values due to its rarity factor.

If you’re about to make your first foray into film photography then going straight to medium, format is a big step and requires some extra commitment as well as, most likely, some extra budget. With the move to mirrorless designs, even today’s digital medium format cameras are now a long way removed from their rollfilm ancestors, so you need to be prepared for a whole new experience that requires both patience and discipline. And it’s going to be same if your last experience of film was a 35mm system.

With the vast majority of medium format film cameras you will have to slow down and be a lot more methodical about how you shoot, especially if you’ve chosen a model that’s entirely mechanical or has minimal automation. But all these aspects are also the positives of using a medium format film camera and the additional involvement that they demand is the real appeal today. You really feel that you’re an integral part of the process of making a photograph rather than just taking a picture. It’s educational, enjoyable and, ultimately, a whole lot of fun.

You will undoubtedly be rewarded for effort.

Read more

Best digital medium format cameras

Best darkroom equipment

Best film - 35mm, roll and sheet

Best film camera

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.