"I don’t believe there’s ever any element of luck in photography" – Jason Ingram shares his secrets to stunning garden photos learned over 25 years

Jason Ingram, the leading garden photographer, has published his first book. We find out more

If you’re into gardens and own a few books that showcase the best gardens in the UK and further afield, the chances are that they feature images from Jason Ingram. A leader in his field, Ingram has photographed many beautiful gardens as a contributor to a range of magazines, newspapers and TV programs.

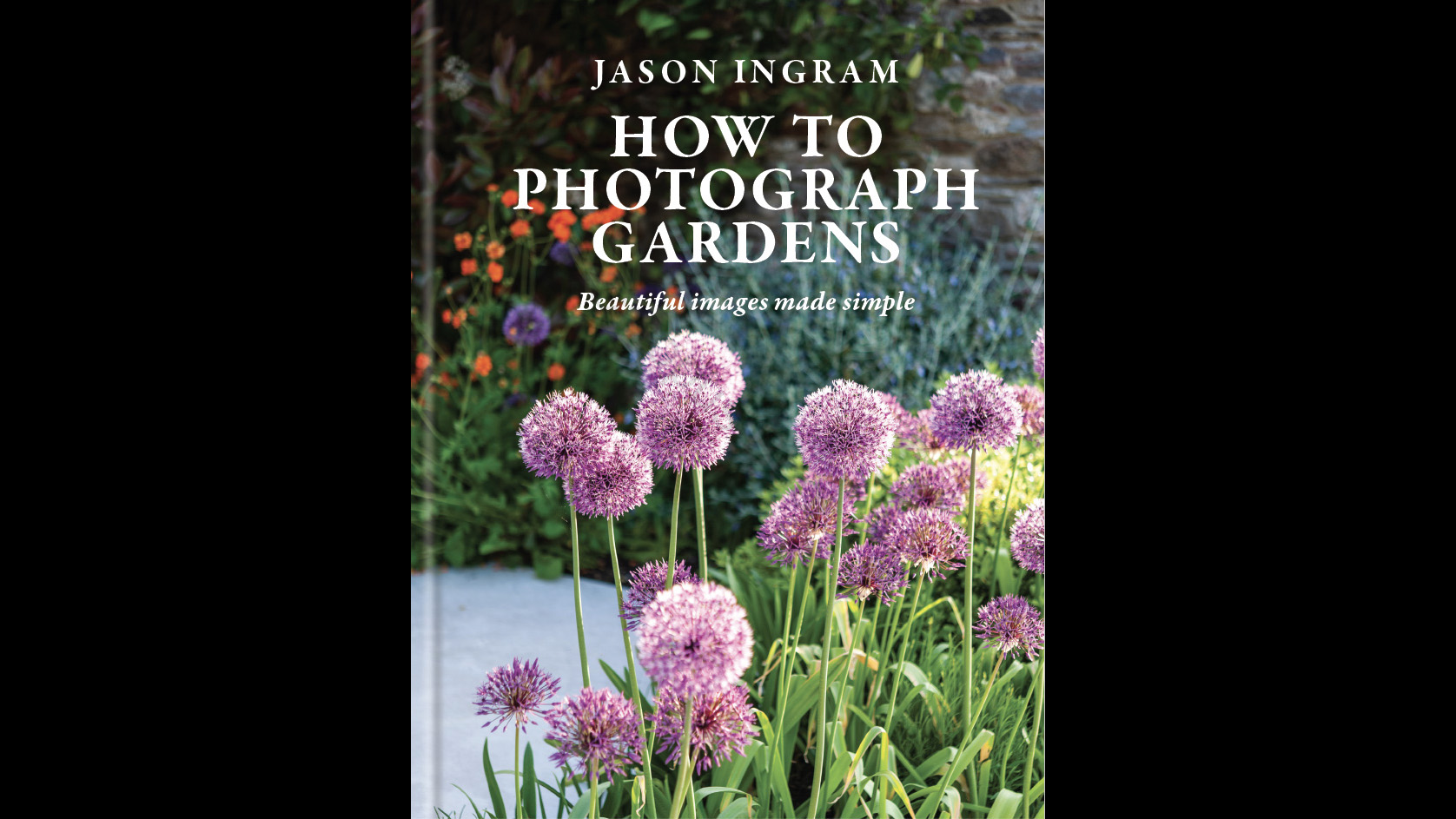

He is also an educator, branching out last year to launch Create Academy’s Online Garden & Landscape Photography masterclass, and more recently to write his first book, How to Photograph Gardens, which contains everything you could need to know about capturing the fruits of leading garden designers, producing visual feasts that help us take a step back from the frenetic pace of everyday life.

We sat down to chat to him about his favorite gardens, the gear he uses to shoot them and the photographic knowledge he's learned over a quarter of a century.

How did you start out in photography?

I was fascinated by the undersea world of Jacques Cousteau and his incredible footage that was on TV in the 1970s. From that point, I was interested in the world of visual imagery, whether moving images or stills, so I knew I wanted to be a photographer, an image-maker – pictures were my thing.

At school, I was always keen on photography and as soon as I could, I went to Salisbury College of Art and studied advertising- and editorial-based photography.

For a lot of my time at college, I would go out with a large-format 5x4 camera and medium format cameras and try to understand the zone system and because of that, I got completely engrossed in all the books by Ansel Adams. For anyone who photographs any form of landscape – I’m a garden photographer but that involves being in the landscape – Adams is difficult to ignore.

I approach the wide shots I take in the same way as I would a landscape. Seeing an Adams print for the first time, I was in awe of his work and its quality. I don’t think anyone has achieved it since.

How did you get your break as a garden photographer?

My first commission as a freelancer was for John Hind’s postcard company. One of the major postcard suppliers in the UK, he commissioned me to update the range of postcards covering honeypot locations in Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Wiltshire.

It was interesting work because there was a particular style and look that you had to capture. I could spend two or three days not getting anything because the conditions weren’t right – you had to have puffy white clouds against a strong blue sky. It was all about making sure a view looked as ‘summer’ as possible.

After that, I went to the north of Canada, shooting landscapes for about eight weeks in -35°C to -50°C (-31°F to -58°F) temperatures, hoping to come home with a selection of rare and saleable stock pictures for a library I was supplying. This didn’t really materialize to the extent I was hoping for, so upon returning to the UK, I assisted advertising and editorial photographers – food, interiors and so on.

Then I started shooting as an agency photographer for the National Trust. That gave me access to gardens I wanted to photograph, out of hours – early in the morning, late in the evening. This opened my eyes to the possibility of becoming a garden photographer, though I had no idea this was even a thing.

I started looking at garden magazines and sent my portfolio out trying to get some commissions. No one was really interested, so I started shooting some work on spec and giving it to the magazines. And that’s how it all started.

I tried selling some work I’d shot in Australia to Gardens Illustrated magazine in the UK, which was a good way of introducing myself, and also photos of a reader’s garden to BBC Gardeners’ World magazine. They liked my work and offered me some other commissions.

Within six or eight weeks, I was asked to shoot with Monty Don for Gardeners’ World. It started from there and now all my work is commissioned – I don’t shoot anything on spec. It has been hard graft and a lot of perseverance.

How did you develop your own visual style – what makes a Jason Ingram garden photo?

Light and how I control it. Without a doubt, light is the number one thing you work with and I always try to make sure I’m working in the best conditions possible. If they aren’t the best, I work around it and return to the garden another time.

I still work in a traditional way, doing everything in-camera, working with graduated neutral density filters and never touching anything like focus stacking or blending exposures. I shoot as I used to with film; I haven’t changed the way I approach photography in the slightest – it’s all very controlled.

How do you deal with working in difficult conditions?

I always make sure I can be where the conditions are going to be favorable. Of course, there are times when you have a week of appalling weather throughout the whole country and there isn’t much you can do about it, but not all my commissions are based on the features of gardens – some of them are about plant collectors.

I might work with a nursery that grows a particular type of plant and need to go and photograph 20 rose cultivars, say, or 20 varieties of lavender. Smaller shots like that, I can either take in overcast conditions and less-than-perfect conditions, or I can go on a hot, sunny day and control the light with diffusers.

I also shoot lots of books for authors on the subject of gardening, and those shoots go ahead whatever the conditions. Images for books like that have a practical focus: there are shots of the author in the garden, so in those cases, I become more of a portrait photographer.

Do you have to be very technical to be a good garden photographer?

Yes, I think so. It helps to fully understand the fundamentals of exposure – whatever type of camera you’re using. In How to Photograph Gardens, I’m trying to share information that I have learned over 25 years of working because I feel that the technical side of what I do is the same today as it was 20 years ago. I apply the same techniques because I’m a believer in the fundamentals of photography.

I use a Nikon Z9, which has functions I’ve never sat down and looked at. You need to understand the basics of photography before you can start to use the technology to your advantage.

That’s why I don’t believe there’s ever any element of luck in photography. When I teach courses, I steer people away from thinking that they got a great shot because they were lucky. I don’t believe in that.

You do get amazing conditions, of course, but we’re talking about the technical side of things. It’s crucial to know what your camera’s doing, when it needs to be on a tripod, when you can use it handheld and so on.

Imagine you’re shooting a garden you’ve never seen before. How long would it take you to formulate what you’re going to do photographically?

Ideally, I will arrive early in the afternoon and have a recce for a couple of hours with the garden owner or whoever meets me, or I might just have a map and go around myself. I’ll aim to shoot that evening and in the morning as well. But that’s not always the case.

Occasionally, I get a scenario where I haven’t seen anything about the garden and don’t know much about it at all. I arrive there before first light and almost have to shoot blind. The only thing I can work with in that situation is where the light is and what the light’s doing.

Ideally, the sun’s going to be out anyway so one of the first things I do is to use The Photographer’s Ephemeris app on my phone. This tells me exactly where the sun is going to be, at what time of the day and whether I can shoot parts of the garden in the morning or the evening.

The key thing for me, because I always like to shoot into the light, is where the light is going to be. As long as the light is coming in from "10 past" or "10 to" the hour in front of me, that’s what I’m looking for. I always like the light to hit in front; I never like it to be behind me because it’s just too flat, even at 4am.

I need to think about getting at least 12 opening spread images – landscape photos of the garden – plus about 12 mid-range shots, longer telephoto lens shots and perhaps 10-20 portraits of plants which are key to the garden. It’s really important I know what the key plants are and the landscape gardener or garden designer will tell me.

Of course, these are the shots I leave to the end because I can control them. Even if it rains, there’s still a good chance that I can get these shots, whatever the conditions.

What is your go-to setup for garden photography?

It would be the Nikkor Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S, which is my workhorse lens. I like to have a 70-200mm and Z MC 105mm Macro with me but, if I had to choose one lens, it would be my 24-70mm.

I also use a spirit level on my camera’s hot shoe – I can’t work without it. I’ve got an electronic level in my Z9 but it’s nothing like a spirit level, which is absolutely bang on. If I ever lost it, I’d freak out and probably cancel the shoot – because there’s something satisfying about being a step away from the camera.

My other essentials are a tripod and a geared head, and I cannot work without a cable release. I know I can use the camera’s self-timer and delay it by two or three seconds but garden photography is so different from landscape photography.

I’m looking at a garden full of plants with moving heads through my viewfinder, which I use more than the LCD screen, waiting for the exact moment when the point my eye is fixed on is as still as it can be. I’d miss that if I’m not using a cable release.

Another thing I always take with me is an A4 piece of card, which I use to ‘flag’ the light. I use it because I shoot with graduated ND filters on an ancient Lee Filters system with bellows. Because I shoot into the light and have the light coming in demanding positions, I make sure I flag the lens constantly. I know that with the angles I like to shoot at, I will have light hitting the lens.

How long did the book take to put together?

I’ve shot the photographs for over 100 books and [publisher] Ilex Press suggested I should do my own book about photographing gardens. Having just finished making an online masterclass, I had already formulated what could go in a book. From start to finish, it probably took eighteen months to two years, and I’m pleased with it.

Which gardens do you love photographing the most?

I like naturalistic gardens, which more than anything else, resemble landscapes. Oudolf Field at Hauser & Wirth in Bruton, Somerset, is a particular favourite of mine. It’s planted like a meadow with paths but hardly any formal structure. I love working with Pete Oudolf.

I recently finished a book with Ulf Nordfjell, a Swedish garden designer. I made 18 trips to Angnas in northern Sweden and the light is something else there in May. There’s no golden hour; it’s more like a golden half-day. It’s remarkable – you can shoot for pretty much 24 hours a day and the sunrises seem to take forever.

Highgrove Gardens in Gloucestershire is another favourite of mine. It’s a lovely garden to walk around and I would say the best time to go and visit is in May because that’s when King Charles’s meadow is in full flower and looks particularly good, although the public is not allowed to take photos of the gardens.

Who is the book for – did you have a particular reader in mind while you were writing it?

Whether you want to create stunning images from your own garden, showcase the gardening business or simply discover a rewarding new genre of photography, the target reader will be a garden designer, perhaps a semi-professional or professional photographer. There aren’t many books out there about garden photography, as it’s quite a specific genre. I should imagine a few of my peers will delve into it.

How to Photograph Gardens by Jason Ingram, published by Ilex Press (ISBN 978-1- 78157-951-0), is on sale now, priced £26 / $33 / AU$53.

Digital Camera World is the world’s favorite photography magazine and is packed with the latest news, reviews, tutorials, expert buying advice, tips and inspiring images. Plus, every issue comes with a selection of bonus gifts of interest to photographers of all abilities.

You may also be interested in...

What do you need for garden photography? A good macro lens will help get closeups of the flowers while a wide angle lens will capture the garden itself. And, of course, you'll need a sturdy tripod as well

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.

- Wendy EvansTechnique Editor, Digital Camera magazine

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.