Kodak didn’t want you to see this and kept this revolutionary camera secret for 25 years

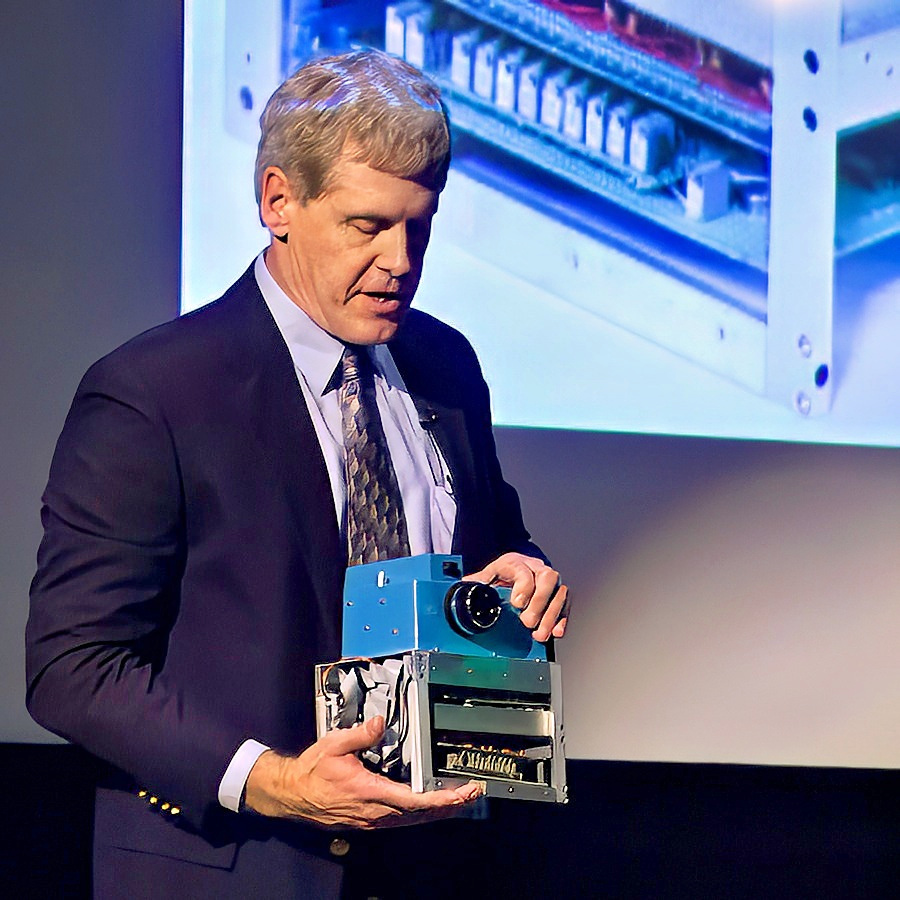

Classic Cameras #13: The 24-year-old engineer who built the first digital camera that weighed eight pounds and ran on 16x AA batteries:

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Early in 1975, 24-year-old Kodak electrical engineer, Steven Sasson, was handed a newly developed CCD (Charge Coupled Device) by his supervisor and asked to “see what he could do” with it.

The conversion likely lasted less than a minute, and the word “digital” was never mentioned. But, with the help of two very talented technicians, Bob DeYager and Jim Schueckler, he designed and built the world’s first working, self-contained digital camera in less than a year.

It was no easy task, for the CCD, from Fairchild Semiconductor, required twelve different voltages and came with a handwritten sheet, detailing the voltage required on each pin. Below was a note from the engineer who’d calibrated the chip. It simply said “Good luck!”

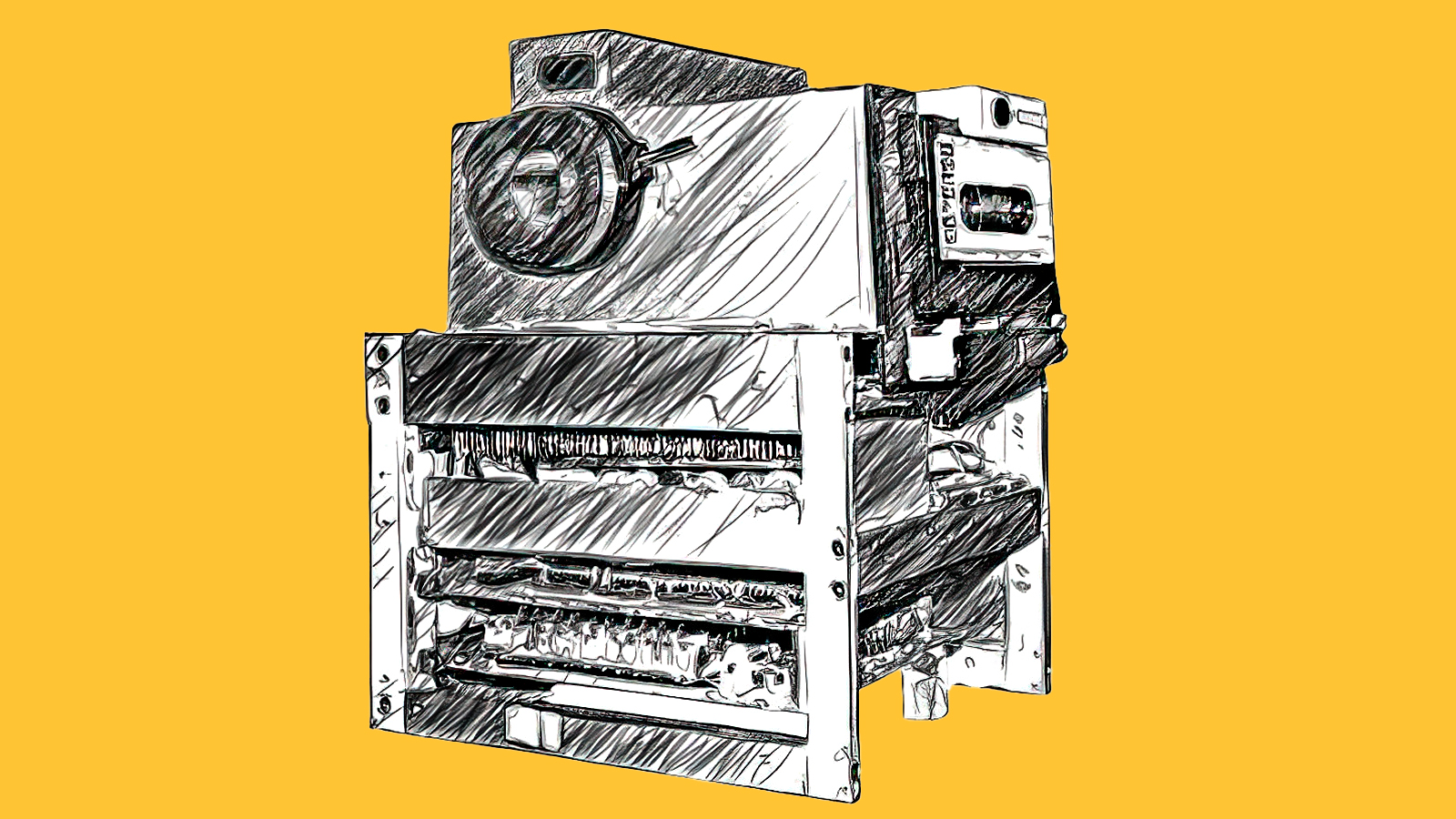

16 AA batteries provided the necessary power, but power consumption was high, so battery life was short. The lens was scavenged from a used Kodak Super 8 cine camera, as the entire project was a low-budget affair. The camera was painted blue, simply to prevent fingerprints marring the aluminum housing and because a can of blue paint happened to be at hand.

The camera weighed 3.6kg (about eight pounds) and recorded a whopping 0.01 megapixel (100 x 100 pixels) black-and-white image on a Philips-style data cassette.

Check out the best Black Friday camera deals

The camera had a simple optical viewfinder (no rear screen, as we have today) and an electronic shutter, with just one speed (1/20th of a second or 50 milliseconds). Sensitivity was approximately ISO 100. The black-and-white image took just 150 milliseconds to be recorded into memory, but a further 23 seconds were needed to permanently store it on the digital cassette tape. It then had to be read into a microcomputer for playback on a television screen. Remember, this was purely a technical exercise, not intended for production, but just to see if digital photography was even possible.

On 9 December 1975, they made their first photograph with the camera, a simple shot of alternating black and white bars. It worked! So Sasson persuaded a nearby lab technician, Joy Marshall, to pose for a photo. She followed them down the hall, to see the result. Sasson said that when it popped up on the screen “you could see the silhouette of her hair,” but her face was a mass of static". She was less than happy with the results and left saying “It needs work”!

But Sasson quickly realized what the problem was and, after reversing a set of wires, the young lady’s image was restored, and digital photography was born. Sadly, he did not save the photo, as the cassette was often reused.

Sasson set the capacity of the digital cassette to 30 photographs, a number chosen to be conveniently between 24 and 36 – the number of photos on a roll of 35mm film. He could have said it could record just one or two, but he knew his bosses would say that wasn’t practical. He could just as easily have chosen 100 or even 1,000, but he also knew that nobody would be able to wrap their head around such a concept at that time. When he first showed his creation to his superiors, in a presentation he called “Filmless Photography,” they were less than impressed.

Sasson was forbidden to talk about the camera outside the company until 2001, when he wrote an article for the 16 October edition of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, which also contained the first public photo of the original prototype. When the news broke, Sasson was in for a treat: “For 10 minutes my kids actually thought I was cool”.

Only one prototype was built. It still exists, unchanged from when it took its last image sometime in 1976. It no longer functions, as the wire-wrap connections used for the digital circuitry were only meant for temporary prototyping use. The camera had no official name, although Sasson admits to calling it some rather uncomplimentary things when it stopped working. Which it did, frequently.

Sasson kept the camera at home for about 30 years. But after its existence became public the Smithsonian asked to display it in their Museum of American History, in Washington DC, where it remained for several years. Today, you can see his creation in the museum in George Eastman House, Rochester, New York.

Sasson told me that when he travels with it by air, to give talks, he carries it on his lap. Needless to say, it attracts considerable attention at both airport security and in flight!

Steven Sasson retired from Kodak in 2009 and, in 2010, he received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation from President Obama.

- "The fall of Kodak wasn't because of digital cameras"

- A history of Kodak: from underdog to household name

- Doing it by halves: the history of the half-frame camera

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

David Young is a Canadian photographer and the author of “A Brief History of Photography”, available from better bookstores and online retailers worldwide.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.