Inside Daido Moriyama’s 'Quartet': The four books that forged the legendary street photographer

Editor and writer Mark Holborn speaks about shaping Quartet, the new Thames & Hudson release that brings together four seminal books from Daido Moriyama’s early career

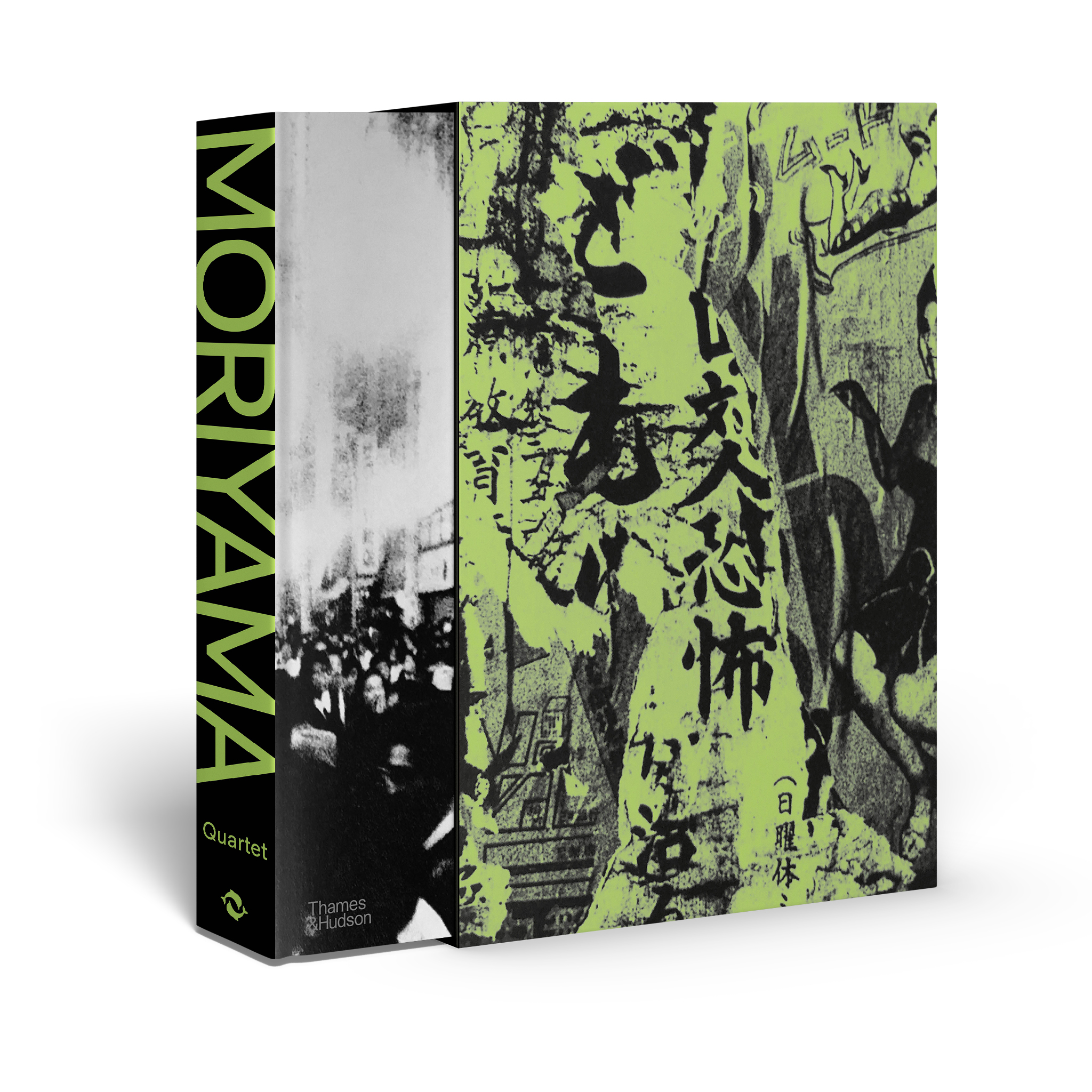

Mark Holborn, whose career bridges decades of photographic practice, publishing and curatorial expertise, is the guiding hand behind the new Thames & Hudson release, Moriyama: Quartet.

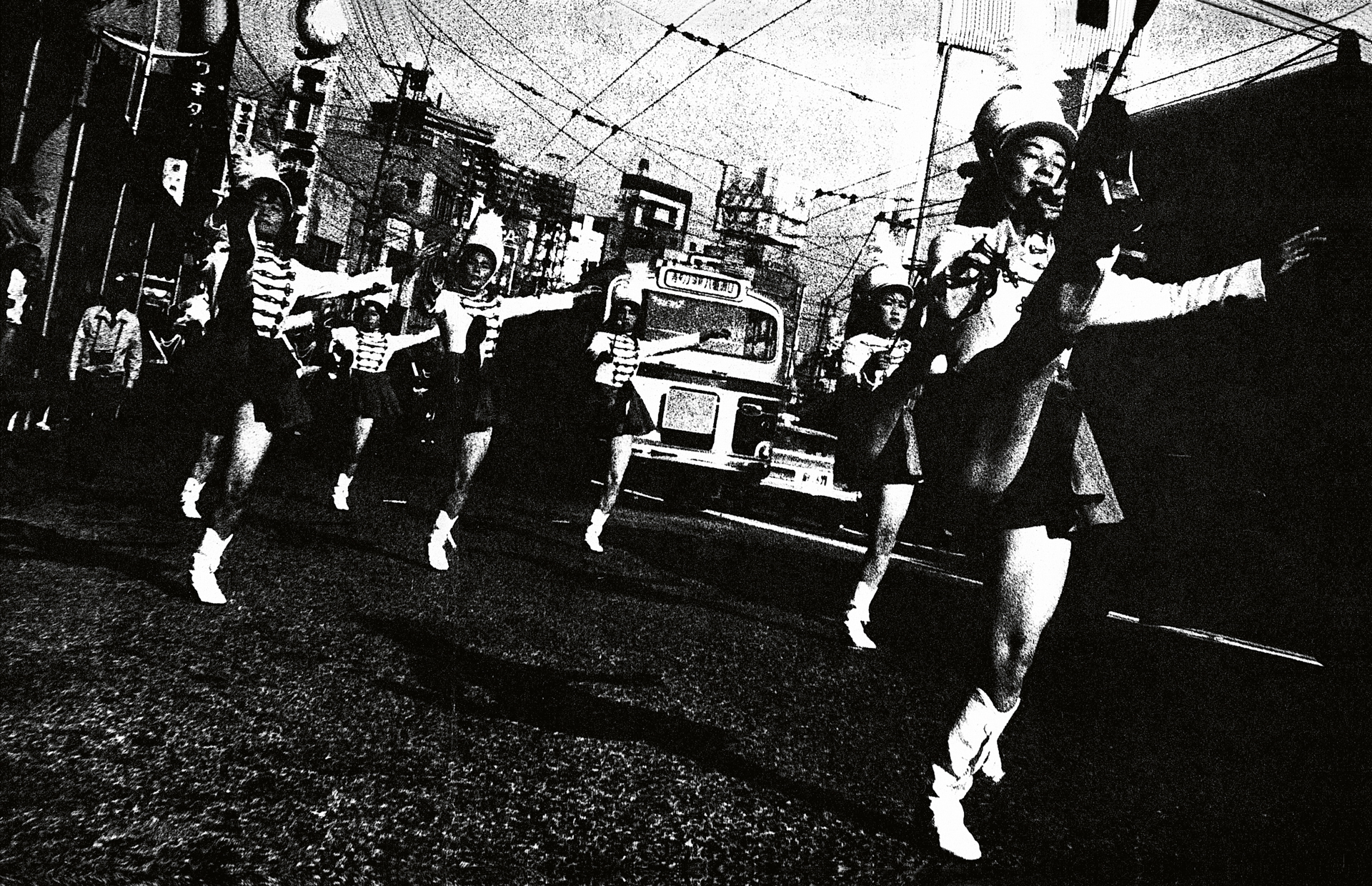

This extraordinary new book brings together four of Daido Moriyama’s formative works – Japan: A Photo Theater, A Hunter, Farewell Photography and Light and Shadow. Books that shaped the photographer’s restless, boundary-pushing vision.

In this volume, the early experiments, obsessions and rhythms of Moriyama’s eye are laid bare, offering a rare glimpse into the foundations of a practice now widely revered. Throughout the book, you can see the journey Moriyama takes in establishing his unique style – a style that has, decades later, become globally recognized.

In our conversation, Holborn shared his reflections on the medium of the photo book, the challenges of capturing a narrative across multiple works, and the instincts that guide a lifetime of editing. His words reveal the meticulous craft behind this publication and a profound engagement with photography itself.

I thought we could start with your introduction to Moriyama's work. Do you remember the first time you came across it?

I think it was the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] exhibition catalog from 1974. I had been in Japan in late '71 through to spring '72 for 6 months, and I had a friend who was a photographer in Japan; he often spoke about Daido Moriyama. The first time I met him was around 1984 in Tokyo, so about 40 years ago.

What was your initial reaction to his work at that time?

I was very excited. It felt like a language I instinctively understood, unlike any other photographers I had encountered.

I knew of his relationship with [Eikoh] Hosoe and his enthusiasm for Shōmei Tōmatsu. I had been very dependent on Hosoe, who was instrumental in introducing me to Moriyama. I could see that his work was different from anyone else’s, and that he was somehow at the center of something very powerful.

Of course, I knew about William Klein and his impact in Japan. Moriyama may have picked up certain stylistic elements from Klein, but his work in Japan is completely different from Klein’s work there. Moriyama presented a visual language unlike anything I had seen in American or European photography.

At the time, people often labeled his work as 'Japanese' because it was high contrast and very graphic. That’s a false generalization. It was simply unlike anything I had seen before. And he was prolific; there was so much work being produced.

Personally, he was also the kindest, most generous person. It was a pleasure to talk with him and be seen by him. He was approachable, modest and sweet-natured. He’s devoted his life completely to his path and has no need for egocentric assertion.

He’s received recognition in his lifetime, both in Japan, where he is highly regarded, and internationally, where he is justly considered a very important figure. There’s a sense of completion in his work.

That leads us on to this new publication. Could you talk a little bit about how the idea for Quartet first came out?

I’d always seen those books as profoundly important. The first three follow a logical chronological progression. In fact, I feel that Farewell Photography, although it was published before Hunter, relates chronologically. Hunter was conceived, and the photographs were made, before Farewell to Photography.

Farewell to Photography is a sort of progression from Japan: A Photo Theater to Hunter. That’s a huge step: he goes out on the road across Japan. Then Farewell to Photography shows him reaching the end of a path.

It’s a time when Japan is socially and culturally exploding, and he’s aware of that. He’s also in crisis himself. There’s a certain Warholian edge to it; it’s a kind of grunge period, and it’s very audacious.

It’s nihilistic, following in the wake of the events on the streets of Tokyo in '68 and '69, the demonstrations, riots, and societal fractures. He reaches a personal dead end. Then he reemerges with Light and Shadow around 1982. He’s complete. The work and the book are amazingly fulfilling. He’s found his language and is executing it brilliantly; the work is perfect at that point.

The progression starts with his first book, which came out of a collaboration with the great theater director Shuji Terayama. It wasn’t Daido’s idea to photograph theater; it was Terayama who said, "Come with me." Hunter is Daido going out on the road. Light and Shadow, I feel, is an assertion: he’s found his language and is executing it brilliantly.

I loved the book when it came out. I saw it in Tokyo, maybe a year after its release. I remember going into a store, seeing a stack of them on a table, and being so excited.

What made these books in particular so central to understanding Moriyama’s practice moving forward?

I think that’s it. Japan: Photo Theater is an interesting book. It’s a very neat book and is underestimated. You can see a beginning in it, and by the time you get to the fourth book, you see that his language is in full flow.

I think the four books form a basic foundation. You see him going from the very beginning to executing this visual language with great accomplishment. From then on, he’s set up. I don’t know how many books followed – fifty or more – but these four are the foundations.

Were there any challenges in bringing the four books together into one volume?

Yes. There’s always the question of having the audacity to edit and sequence the work. I had this with Record. With Record, it was essential, because otherwise we’d end up with a thousand-page publication. In Record, I tried to be loyal to Moriyama’s own juxtapositions and very rarely introduced my own.

For these books, I didn’t have to do much; I simply omitted certain things, reluctantly. In Japan: Photo Theater, I won’t go into too much specific detail, but there are a couple of pictures, really famous ones, that are not in the book.

I’ve talked to Daido, and I have an idea for another project. In that project, the two missing pictures will appear. Part of the reason I didn’t include them here was that, while they are good pictures, they color the presentation in a way I didn’t want.

They’re in the MoMA catalog from New York, and I always associated them with Japan: Photo Theater. The last thing I wanted was for someone to open the book and feel like they’d seen these pictures before. I wanted it to feel fresh. For better or worse, that was my decision.

It’s terribly difficult to cut anything, but I also had to think about making the four books into a single, coherent volume, not just separate books edited down. I had to introduce elements to bring it all together so it doesn’t feel disjointed. You enter and exit it as if you’re going through four different sections.

Unlike the Record publications, which might have twenty or thirty sections, this has a musical equivalent in my mind; chamber pieces up front, leading into full flow at the end. They are four passages, and by putting them under the same cover as one book, I’m suggesting there are links between the sections, even though they differ in subject and execution. In my eyes, they form a coherent whole.

You have a point of entrance and a point of exit, which is difficult. With Record, there could be thirty passages, but the aim is always coherence. Everything I do, I want it to have a beginning and an end, to exist as a book with its own sense of narrative. I’m not interested in anthologies; I want something more powerful than an anthology.

His earlier work was seen as radical for the time. Do you think the world has caught up to his vision?

Seemingly. It’s quite an interesting question, isn’t it? Seemingly, it’s taken 30 or 40 years. I feel the same about [William] Eggleston. He had the backing of a show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974, and people wondered why. Why were these so-called snapshots suddenly in a museum?

It took a long time – since 1974 to around 2010 – for the market to realize there was something there. One of the new large inkjet prints, which people were initially negative about in the photography world, sold for a lot of money. I know one sold for over a million dollars. It’s an iconic image, and it shows that in that case, his work has crossed into the mainstream of art.

You start to see Eggleston’s influence in album covers and movies. I was watching Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and there’s a shot on the plane framed exactly like an Eggleston. It’s pervasive; you see or imagine the influence.

The same must have happened with Moriyama. When he had a show at the Tate around the time William Klein had a show, people outside the normal photo world started seeing it. These visual languages travel, and their imagery is replicated. In advertising, for example, art directors may suddenly go high contrast, introduce grain, or blur. Elements reflecting the intensity of Moriyama’s images.

Moriyama has photographed all over – Los Angeles, New York, Gothenburg, Morocco. His perception and resulting language are not confined to the backstreets of Shinjuku or Osaka, just as Eggleston could photograph outside the Mississippi Delta or Tennessee. Moriyama can photograph in England or Boston. He knows how to work anywhere.

People internationally recognize familiar markers: a Main Street, a KFC. What was once a peculiarly Japanese experience becomes universally recognizable. The collision between old culture and ubiquitous new culture exists everywhere.

So yes, his work becomes more accessible. Many of the feelings of spectacle, or even alienation, are common across cities in Europe, America, and Japan. You could make similar pictures in China; the context differs, but the experience resonates.

I’ve found this with Eggleston, too. People never fully understood him at first, but his vision is contagious. Once you’ve seen it, you’re never the same. The ordinary, a Coke can on a table, for example, can be transformed into an image that resonates beyond simple abstraction. The same happens with Moriyama: you see a scene on a street in a different city or continent, yet it feels familiar.

There might be someone standing in a doorway, isolated and lonely, and you project onto it everything from your own surroundings. It’s almost an invitation to look further. It changes the way you see your own streets. That’s what good art does.

It’s funny you bring up Eggleston, because the next question was: having worked on books focused on William Eggleston and Lucian Freud, where would you place Moriyama in the broader visual landscape?

I think he’s hugely important. My engagement with Moriyama’s work is similar to how I’ve been engaged with William Eggleston or Lucian Freud.

These encounters happen partly through instinct, and if you’re fortunate enough to meet a great figure, they shape the way you see the world. I’ve been privileged to be influenced by contact with some remarkable artists, and they all leave a mark. Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, William Klein, Lee Friedlander, Josef Koudelka all created new languages, but it happens very rarely.

They do it because they’ve absorbed the history of the medium, out of intelligence, and because they can’t do anything else. It emerges naturally, like writing a song. It becomes as instinctive as eating or breathing. The three figures we’re talking about, Moriyama, Eggleston and Freud, left behind work that is unmistakably theirs and that shaped a path forward.

Years ago, when I was working in magazine publishing, I’d look at portfolios. Most photographs I saw looked like photographs. Only very rarely did someone come in with something truly new, something I’d never seen before.

Even when I’m taking photos myself, in full flow on a street, the images I make are shaped by what I’ve already absorbed. My instincts are born of memory and experience and guide what I capture. Yet it’s unlikely that I’d enter entirely new territory.

Moriyama and Eggleston are among the few who have. Freud, too, worked within and against the weight of art history, in ways that were often unfashionable, but persistent.

Moriyama is the last of a particular generation: those born during World War II, living through the aftermath and Japan’s post-war rebirth. Their references are rooted in a specific historical, social, and cultural context – the austerity, reconstruction, and transformation of Japan. Later generations, born after the 1970s, don’t share those experiences. They live in a digital age, with entirely different references and access to global culture via the internet.

You’ve edited some incredibly important photography books. What draws you specifically to the medium of the photo book?

In Japan, the photo book is a very particular medium. My initial interest was in Japan itself, not photography, so my engagement with photography grew out of wanting to understand Japan.

Early on, I realized that in Japan, books were often the primary vehicle for photographic work. Exhibition spaces were limited, but the books were beautifully produced. The quality of production, especially gravure printing, was astonishing and affected the way the images looked.

Japanese books also reflected a distinct visual sensibility, a different organization of space compared to Western design. They provided access to thought processes and narratives that couldn’t be expressed elsewhere.

For example, my first exposure was Hosoe's portraits of the writer Mishima. From there, I discovered Kamaitachi with the dancer Hijikata. Those books were deeply narrative, often based on memory rather than present reality. Photography, I realized, could explore memory – the past, childhood experiences, psychological landscapes - that painting or writing might not convey.

Outside Japan, I also wanted to understand the American tradition of photo books. Working at Aperture was a huge step; I saw the production of books by Edward Weston, Paul Strand and others, and the level of expertise was unmatched in Britain at the time.

Studying the lineage, from Stieglitz to Walker Evans to Robert Frank, then Eggleston, revealed the importance of narrative in photography. Photographers like Nan Goldin were also constructing narratives, and the book form made that narrative explicit. Within 150 pages, you have a beginning, middle and end, and you can shape the story through editing, forward and backward, much like film.

Today, what once felt arcane or esoteric is much more mainstream. Publishing houses, like Thames & Hudson, are enthusiastic about work that would have been impossible ten years ago.

The global infrastructure – connections in Paris, New York, the West Coast – makes producing books economically viable, even outside Japan. That means the work can continue, and the medium lives on, which is ultimately the most important thing.

As someone exploring the editing process myself, do you have any advice for getting started in curating photography books?

I can only speak from my own experience, but I have a strategy that I apply across a wide range of subjects, from fashion photographers to war photographers.

The first thing is to understand what is at the core of the work. What’s at the very heart? Once you know that, you can structure the book around it.

You need three key points: a point of entrance, a core and a point of exit – essentially, your beginning, middle and end. With those in place, you can fill in the spaces between. Your intuition will guide you to the core, because you’re naturally attracted to it. Ask yourself: Why does this work draw me in? That’s your clue.

Then, consider how to take the reader into it. The opening should be like a door, not a wall; you’re inviting the reader in. The ending, if strong enough, should be a full stop, a place from which there’s nothing beyond. That sense of closure is essential to a compelling photo book.

With Quartet, what do you hope readers, photographers or both, take away from this book?

First, I hope they realize that [Moriyama]'s a great photographer – though, of course, many already know that, which is why they bought the book.

Beyond that, I want them to enter the drama of the pages and the sequence. I want them to be enticed, seduced, taken in, their senses turned upside-down.

By the time they reach the end and put the book down, I hope they go out into the world and see it differently. I reference this at the end of my text. A cat in the yard, a bit of broken glass, the broken bottle in the undergrowth. These small details suddenly become noticeable. That’s the gift.

Quartet is more than a collection of four early books; it’s a journey into the raw beginnings of Daido Moriyama’s vision, a chance to step inside the language that would shape a lifetime of radical photography.

Thanks to Mark Holborn’s careful editing, the volume reads not as an anthology but as a single, resonant work, alive with the rhythm of Moriyama’s restless eye.

For those who want to understand the foundations of one of photography’s most influential figures, this new Thames & Hudson release is essential – and it’s available now.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You might also like…

Take a look at the best books on photography and, if you're interested in creating your own, check out the best photobooks. You can also learn more about some of the best photographers ever.

Kalum is a photographer, photo editor, and writer with over a decade of experience in visual storytelling. With a strong focus on photography books, curation, and editing, he blends a deep understanding of both contemporary and historical works.

Alongside his creative projects, Kalum writes about photography and filmmaking, interviewing industry professionals, showcasing emerging talent, and offering in-depth analysis of the art form. His work highlights the power of visual storytelling.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.