Interview: how photographer Sandro Vannini captured Tutankhamun’s tomb

Sandro Vannini on his challenging project that documents the tombs of the pharaohs and ancient Egyptian artifacts

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sandro Vannini is an Italian photographer and filmmaker who began his creative career in the early 1980s. Since 1997 he has been best-known for photographing ancient Egyptian culture, for which he has special permission to access sites that are forbidden to the public. Vannini has pioneered techniques to shoot digital images in the extreme temperatures of the Valley of the Kings, including in the tombs of the pharaohs. His images are among those assisting the work of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo in the restoration of artifacts. Since 2016, he has been directing and producing television programs in collaboration with Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass.

Archaeologist Howard Carter’s eight- year-long excavations in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings culminated on 4 November 1922, with the historic discovery of the steps to the tomb of Tutankhamun. Carter began taking photographs himself, but quickly realized he required a professional photographer to document the excavation of the tomb and its artifacts. Harry Burton, who had been working in Egypt for 12 years, was loaned to Carter’s team. Burton shot straight on to glass-plate negatives, coated with silver nitrate, with a large-format camera. His imagery included establishing shots within the tomb to note the positions of the treasures, close-ups of each artifact and documentary images, such as Carter inspecting the casket of Tutankhamun.

While working in the tombs, Burton illuminated them with electric bulbs rather than flash, and positioned reflectors and mirrors to create special lighting effects. He used a neighboring tomb, KV55, as a makeshift darkroom, and had to meet Carter’s rigorous demands for photographic quality. Carter wouldn’t move on to the next stage of the excavation until he’d approved each image. Over 10 years, Burton shot around 1,400 images, many of which remain iconic. Given the conditions Burton worked in, and the comparatively primitive equipment he used, the quality of his images was astonishing.

In 1997 – 75 years after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb – Sandro Vannini made his first trip to Egypt to photograph Unesco Heritage sites for a book project he was working on. Like Burton, he was determined to tell a story and document the archaeological aspects, but also to photograph many places and artifacts in lighting and detail that had never been seen before. Many of these shots feature in his book King Tut: The Journey through the Underworld...

01. Did you always want to be a photographer?

No, for a long time I thought I'd become a writer. However, I was always taking photos and looking at photographers online. I think my love of writing was always about documenting and making sense of the world around me, which in turn influenced the way I shot photos as well. Photography also just felt a lot more like an innate talent to me, so when it started to dawn on me that you could work as a photographer, I knew that was what I wanted.

02. What drove your initial interest in photography?

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

I started to take photographs when I was 13 or 14. But, as a professional, it started in 1982, when I was 23. I started with shooting film; then I moved to digital when it arrived.

03. How did you first get involved in photographing Egypt?

I started as a climbing, mountaineering and cave photographer, so my approach with photography was mostly geographical. I grew up with Italian magazines like Epoca and, of course, with National Geographic. I started to work for Instittuto Geographic, at De Agostini in Italy, in 1983. For many reasons, in the 1990s I started to do more art, people and food alongside the geographical work. My activities moved into both contemporary art and ancient art and a lot of architecture; mostly architecture of old buildings and heritage in general.

From the beginning of the 1990s, I started big productions about Unesco Heritage sites for the Bertelsmann Group books. In 1997, I went to Egypt for the first time to make a chapter in this book series about Egyptian heritage in the Unesco list. When I first went to Egypt, I realized there was a lot to do, and a lot that wasn’t done before, both in terms of a normal storytelling and in the archaeological field.

At the beginning, I started to use digital during post-production, but I was still shooting with film, because at the beginning, digital was not so flexible. At that time you’d make a 4 x 5-inch shot with film, then scan it with the best scanner available. This made it possible for us to start making post-production at a high level, even if the files weren’t as big as the ones we produce today. It was a case of stitching photographs to make big pictures in places where it wasn’t possible to have the entire vision, because it was too tight [to shoot a single image].

04. Did you study the work of earlier photographers who had shot in Egypt?

Not much. I don’t want to seem arrogant but, because my photography was connected with the technology, I worked with technology like a pioneer. My style of photography isn’t a style I can find in other photographers in the field of archaeology. About 15 or 20 years ago, I was doing what a lot of photographers are doing today, so I never had another photographer to refer to.

05. What sort of cameras and equipment do you work with nowadays?

In this book there are maybe 10 old pictures shot with film, maybe less. The pictures in the body of the book are all digital. This digital photography was done with only two cameras. In the beginning I worked with a Silvestre camera with Rodenstock lenses and the multi-shot Imacon digital back. The Silvestre camera was very small, so we were able to adapt the use of this camera in many structures [and locations].

In 2012 I switched to the Hasselblad H4D, the multi-shot one. [The H4D-200MS combines shots to generate 200MP-plus files.] The kind of work I’d been doing at the beginning with the Imacon back was more complicated than with the Hasselblad, but at that time it wasn’t possible to have such a simple digital camera with that quality, because the Imacon digital back was the highest-performance digital back on the market when I bought it.

06. What major challenges do you have when photographing in tombs?

At the beginning, the main issue was lighting. All of the photographers before me used normal yellow lights or flashes in the Valley of the Kings. None of them had ever used HMI lights [high-quality lights often used in movies], but we brought a huge number of torches there, with a generator outside. In the Valley of the Kings the electricity [supply] isn’t stable, but our electrical system requires a lot of power and has to be very stable so we were obliged to have a very big power generator outside to provide all of the electricity for lighting, computers, cameras... everything.

Another big challenge in Egypt is the heat. The big tombs are deeper in the ground, so the temperatures are very stable during the summer and winter. But the small tombs that are on the surface are very close to the opening door. In summer they’d be more than 50°C and, of course, all digital equipment – computers and cameras – always has problems when you work at very high temperatures.

These tombs are never clean – I found newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s on the ground in some tombs, so nobody had cleaned the tombs in 80 years. There is also very soft, light dust – like a powder – and when you move this dust goes everywhere, inside the cameras and inside the ventilation of the computers.

You cannot bring in air conditioning to bring down the temperature, so the only way was to bring ice inside aluminum boxes. These boxes were the table on which we were using the computer, and where the camera would wait to be used. You have to have a system to downgrade the temperature without having any kind of ventilation that would move the dust.

07. Out of all of the images in your new book, which one was the most difficult to shoot?

Digital post-production isn’t a way to make photography easier. It is a way to solve something that isn’t possible with a normal shoot. In my opinion this is the [best] approach to digital photography.

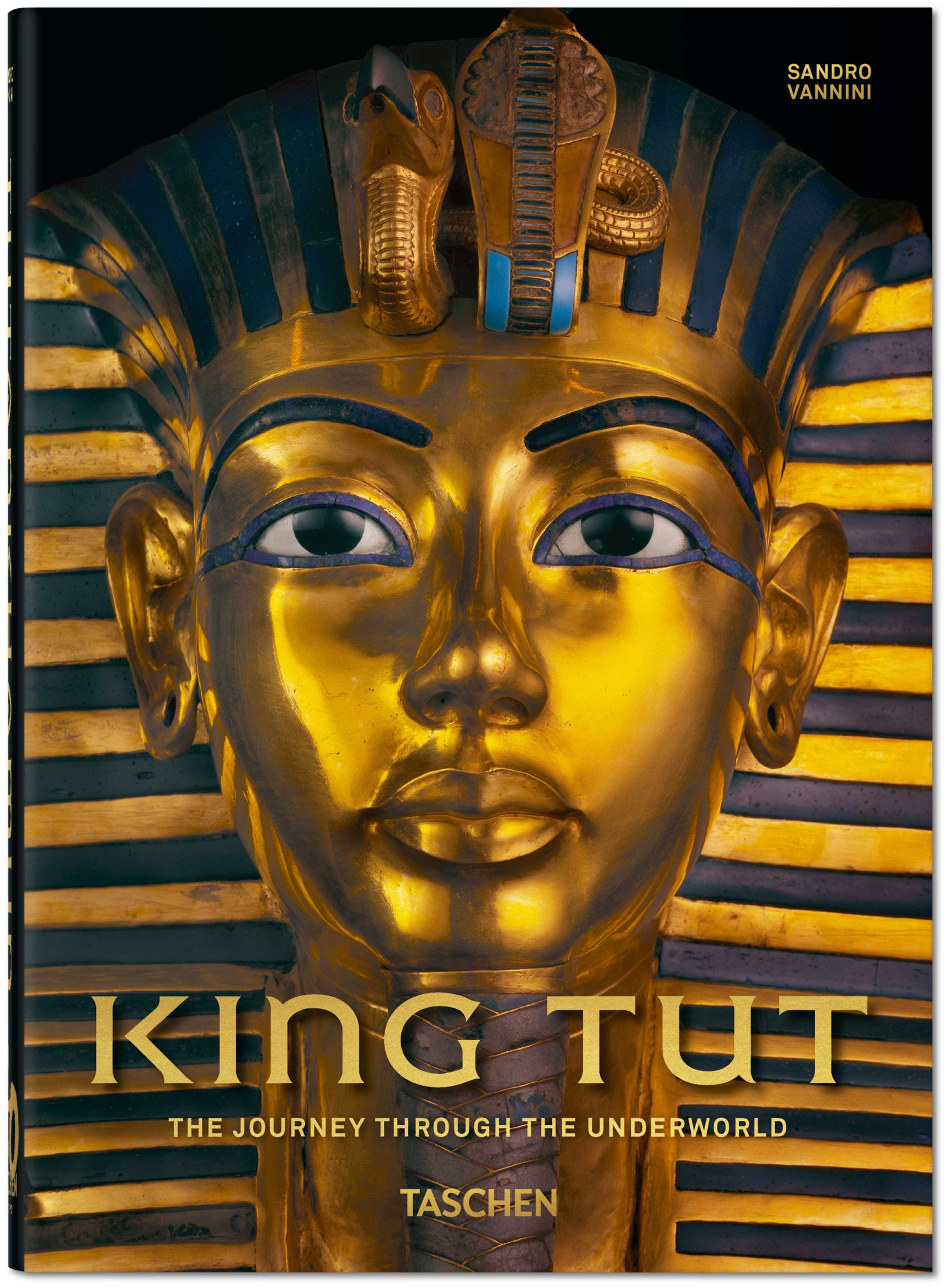

The mask of Tutankhamun that’s on the cover of the book is gold inlayed with a lot of different stones – these can go from a red amethyst to the lapis lazuli and other darker blue stones. The difference in the exposure from the point at which the light touches the gold, and there is a flare, and the lowest point in exposure – the very dark blue stone – is more than 10 stops. No one camera is in the condition to record a 10-stop range without using software.

When I read that a camera has 15 stops of dynamic range, this isn’t real. This means that when you shoot with this camera you can typically shoot 15 stops and you can go with post-production everywhere [in the picture] and make more light here and less light there. But if you want to record a color exactly as it is, you cannot profit from the 15 stops of dynamic range – you have to bring the exact light that stone or metal needs to have.

So I only had one way to do this: to make 10 pictures working on the 10-stop difference between the gold and the dark stone, and to make a picture for the gold and then go down [in exposure] in 10 pictures to arrive at the [correct exposure for] stone. The same pictures were done with the multi-shot assistant, so that’s 16 shots for each picture. So, to do the mask, I shot 160 times. Then, in post-production, we took out from each shot – from each layer of this big sandwich of pictures – the part that was the best shot at the correct exposure. To do something like this, you have to decide what to do at the beginning; it’s not something that you just start.

08. What editing software do you use?

Mostly I prefer to do the color control on the software of the camera, like using Focus for the Hasselblad. Color control is usually something we bring [in] at the end. For the most part I shot [color] levels very neutral, because I prefer to reach the color when we finish, because you have the parameters to arrive at the original color. Then most of the work is done with Photoshop, which is actually the only platform in which you can find nearly everything you need. It’s just a matter of being passionate [about editing].

This is not my job, by the way, but I usually direct it. I’m very involved, because it’s me who’s decided to make 10 shots of the mask and then to take out all of the different layers. I know how the software works, but it’s not me in front of the monitor for three weeks!

09. Your macro images have highlighted details in the artifacts that had never have been picked up before – how did you shoot them?

I’ve been working with macro photography a lot, because in Egyptian art photography jewellery is my first love. I never had the opportunity to go to the Egyptian Museum and take a space somewhere and set up a studio. If you go to do anything like this in any large museum in the world the curator has to bring the object to you and you photograph it.

Each time I work there I have [about] 15 people around, mostly from the Egyptian Museum. They stay open for you, give you the object, you’re set up for shooting and you have three to five minutes at the showcase – it means I was always obliged to find a solution for this. When we started to shoot this kind of photography, for the first book I did on Tutankhamun’s treasure in 2007 or 2008, I brought a black cube tent to the Egyptian Museum, which was 2.5 meters in size, to diffuse the light on the side. I was putting this big black tent over the showcases, so we took out the glass, and I had found a way to light the objects without the need for people to come anywhere near me and have any impact on my lighting.

To make macro photography like this is not easy, because when you do macro photography with multi-shot technology it means that your whole system has to be very stable. A movement of just a couple of millimeters would make it impossible to wrap up the final image, so it’s very tough.

I always spent all the necessary time to do this, even if it was only two pictures per day, to have things exactly as I wanted. In the beginning I was working with bellows with the Silvestre camera and Rodenstock lenses. Now I shoot most macro photography with a very good Hasselblad lens and, of course, a huge amount of different lighting systems. The setup for each picture is a story in itself.

10. What should people thinking of getting the book expect to see in it?

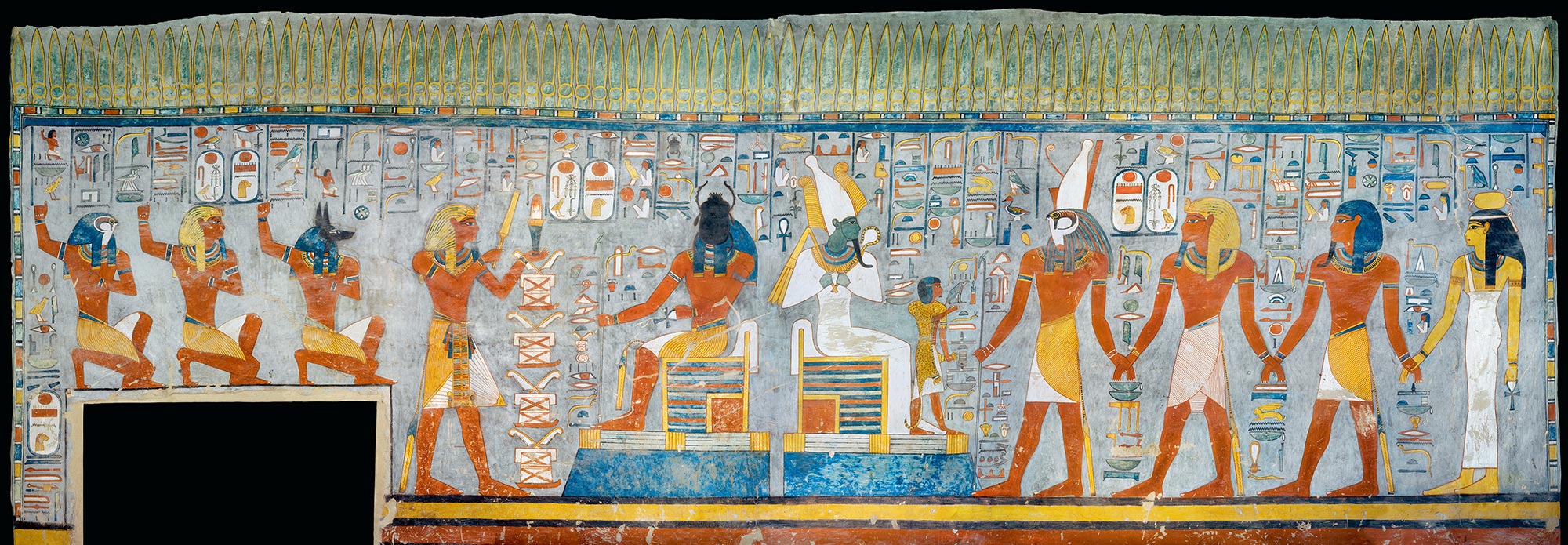

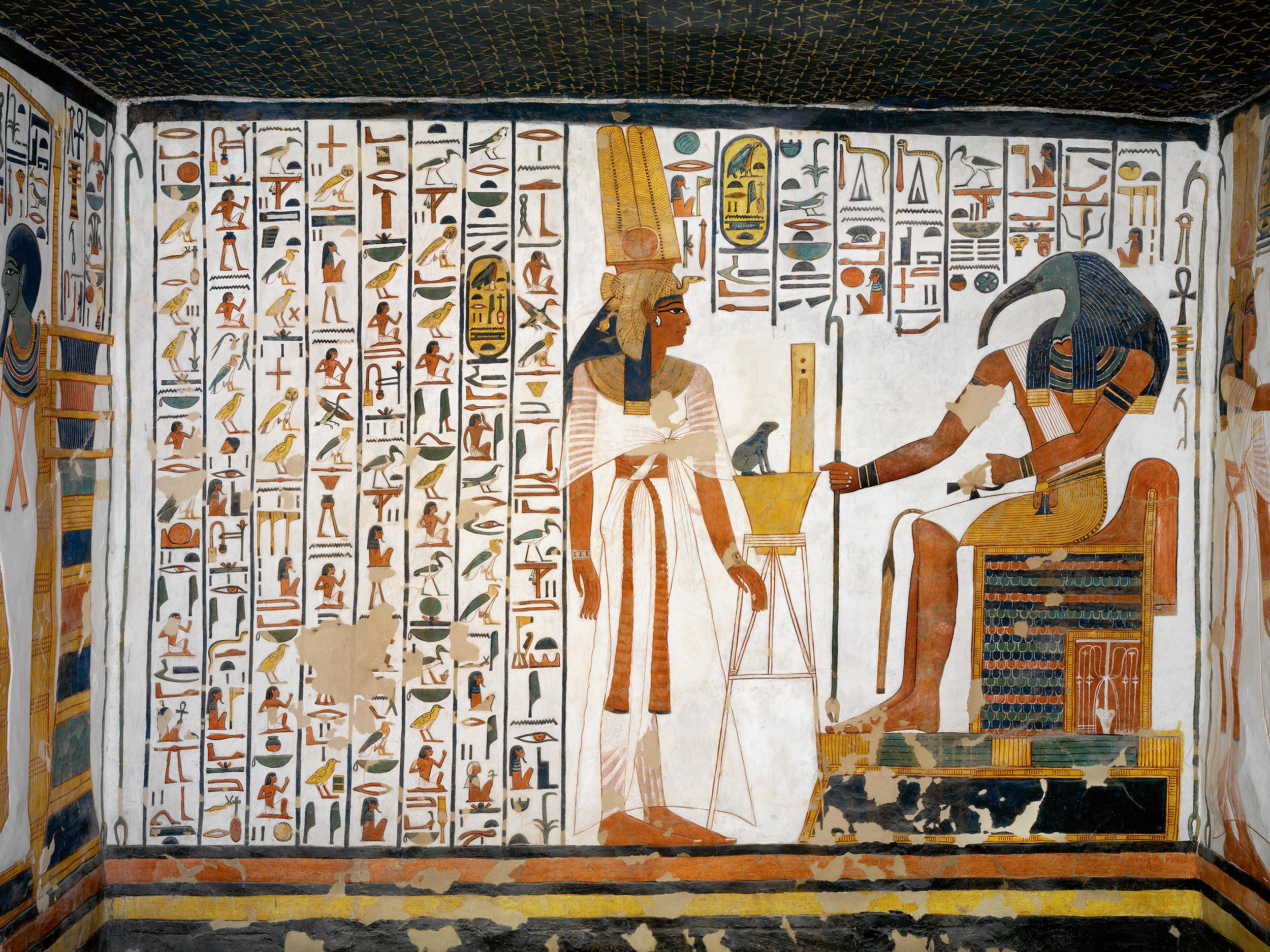

This book is a new approach to the subject and topic of Tutankhamun. Until now it has only been visualized in books in one way – Tutankhamun’s treasure. For this book we decided to take a completely different approach – to use Tutankhamun like our ‘testimonial’ and look at his voyage to the underworld. This is the voyage that every pharaoh is called to do after their death.

The afterworld for ancient Egyptians was like a separate, second dimension that is parallel to our world. The dead are near to us, living in this parallel dimension. When anybody dies they have to do this voyage, where there are plenty of dungeons and plenty of rooms to go through to arrive at the eternal life. Tutankhamun is the person who is guiding us, and we are following his path from the dead to eternity.

The underworld is not a bad place – if you have been a good person in your life, then the rest of your life in the eternity will be fantastic; it will be paradise. So there is a lot of joy and color in this. To illustrate and make a visual book about the voyage in the underworld was my objective.

It’s about the soul of ancient Egypt, because everything is related to this. It’s the best way to understand what you go to see in Egypt because, without understanding this, it is difficult to understand more than what’s on the surface... like how big the pyramids are, how nice the statue of the Sphinx is or how they built this 5,000 years ago. There is something more, and to approach Egyptian civilization it’s important to learn this basic part of their religion, otherwise it’s a superficial approach.

We wanted to produce this book to make available for everybody these 20 years of photography, dedicated to this fantastic civilization that is a part of our religions and our roots in Europe and in the Mediterranean Sea. We are all still connected with this kind of civilization today.

Read more

Best macro lenses in 2021

Best lenses for travel photography in 2021: perfect all-in-one superzooms

Best photo-editing laptops: top laptops for photographers

Best free photo editor: free software that still does a great job