How to always get exposure right – exposure settings explained

We explain the main ways to control exposure, and when to use each option

Unless you tend to stick to your camera’s Auto option, you’ll probably be aware of the many ways in which you can adjust exposure on your camera.

Those set in a particular way of working may forgo many of these for one or two of their preferred methods, but for those getting to grips with their camera, knowing which one to use in a given situation may be confusing.

Should you, for example, use exposure bracketing or exposure compensation? Or perhaps just shoot Raw and tweak exposure in post processing? If your images are a little dark, should you switch to a different metering pattern or would it be better to use a dynamic range adjustment setting? And what about the manual exposure mode?

The simple answer is that all of these can be useful, but there may be good reasons why you'd want to use one over another in a given situation. This is what the following article will explore.

Exposure compensation

Exposure compensation allows you to bias your an image's exposure either towards underexposure or overexposure. You can typically adjust this in fine increments of 1/3EV or 1/2EV.

When to use it: This is useful when your camera consistently gives you a meter reading that doesn’t quite work for you.

So, if your camera is consistently capturing slightly dark images, for example, adjusting exposure compensation by +1EV or so will ensure they consistently turn out closer to what you’re expecting.

This could be, for example, because there are lots of bright or shiny elements in the scene that cause your camera to underexpose, or because you’re shooting darker details, which the camera may overexpose instead.

Exposure compensation is also useful when shooting a subject against a differently lit background, something that often fools a camera into giving inappropriate exposure.

Remember that if your conditions change you may no longer need this, so always remember to return exposure compensation back to 0 once you’re finished with it. Otherwise, it will continue to affect subsequent images.

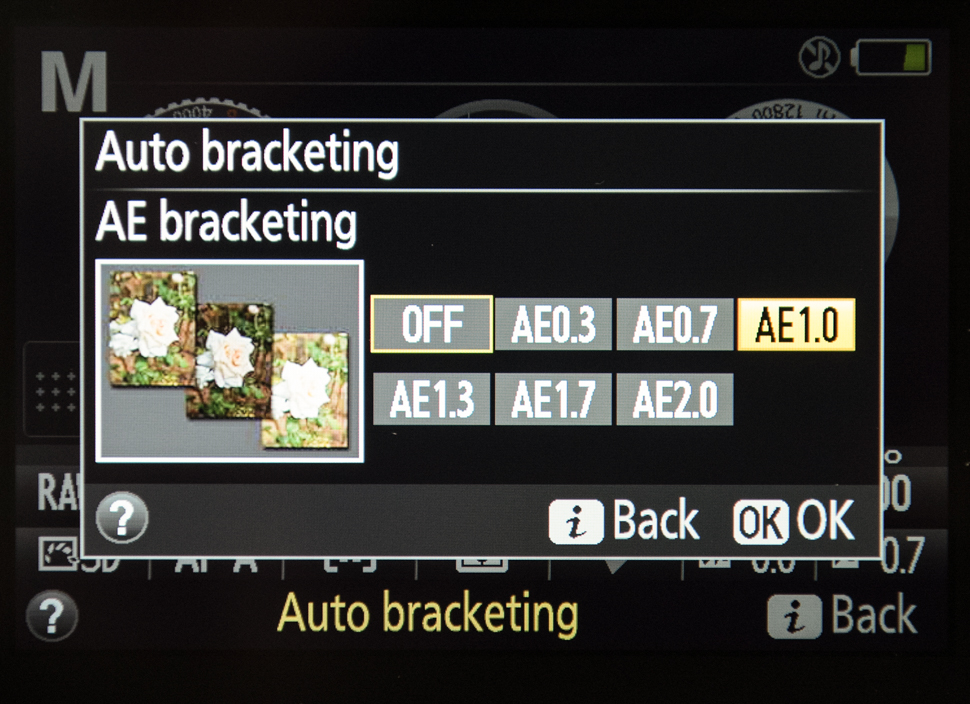

Bracketing

Bracketing, or Auto Exposure Bracketing, usually results in one standard image, one image the camera deems to be unexposed, and an image the camera considers overexposed.

By giving you three images (or five, or seven, depending on what your camera allows and how you have it set up), you increase the chance of ending up with one image with the most appropriate exposure.

When to use it: Bracketing is useful in many situations. You can, for example, use this when lighting conditions are constantly changing, such as when shooting under flashing or constantly changing lights. Performance photography is one example of this.

If you’re using a tripod for a landscape or a similar scene, you can use this to take three identical images with different exposures, and blend them together later in post processing. This way you can end up with a single image with a wider dynamic range than what’s normally achievable by the sensor. This technique is known as High Dynamic Range (HDR) imaging, and this is the principle on which in-camera HDR options work.

Useful tip: If you know that you are unlikely to need one of the exposures when bracketing, you can use this feature in conjunction with exposure compensation to give you two exposures in the direction of your preferences.

So, let’s say you’ve activated bracketing by 1EV each way so that you have one standard image, one image underexposed by 1EV stop and one image overexposed by 1EV stop.

If you don’t think you’ll need the underexposed image – instead, you’d rather have one normal image and two overexposed ones – simply apply +1EV exposure compensation and the camera’s ‘underexposed’ image will be the standard one, leaving the other two images as overexposed by different degrees.

Manual-exposure mode (M)

This mode lets you change aperture and shutter speed independently of each other. This differs from options such as Aperture Priority or Shutter Priority, where changing one setting automatically affects the other.

Although the camera still uses the metering pattern you’ve selected to judge exposure, you will need to adjust each parameter yourself. This can take a little longer in practice, but it gives you plenty of control.

When to use this: This option is particularly useful when you may want to alternate between adjusting exposure by changing shutter speed and aperture. So, taking a moderately-lit scene as an example, you can quickly combine a wide aperture with a fast shutter speed, or a small aperture with a long shutter speed, or a value somewhere in the middle for each.

Manual exposure is useful when you don’t want the camera to change aperture or shutter speed if and when it deems it necessary. This is also useful when using flash, particularly as you need to ensure your shutter speeds stay at an appropriate level for flash synchronisation.

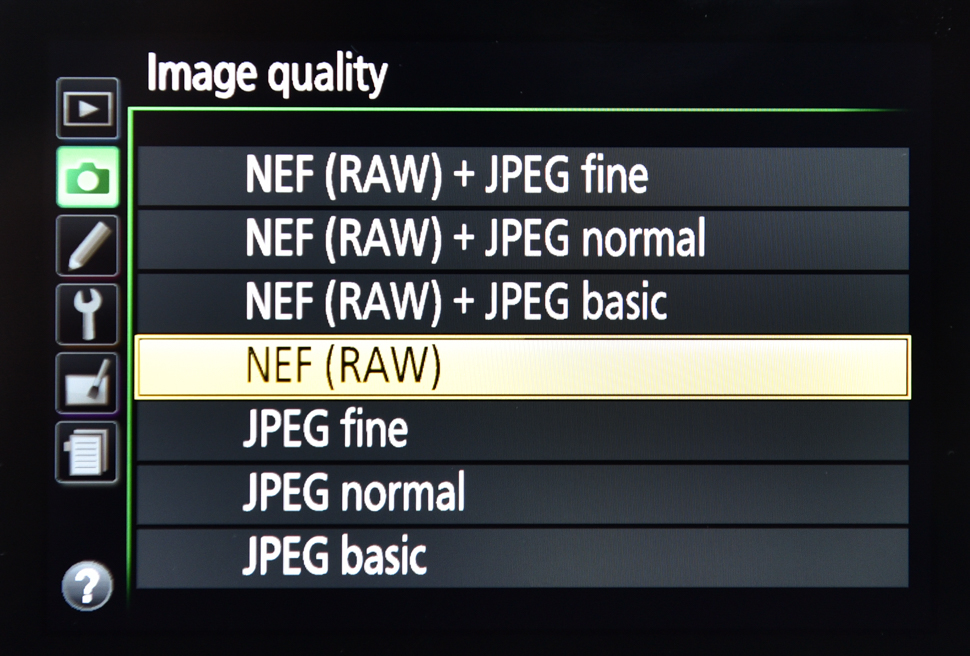

Raw shooting

Shooting Raw images allows you to alter many settings after you’ve captured your images, with freedom to make those adjustments without degrading image quality.

While you still need to pay attention to your exposure when shooting Raw images, you can make tweaks to overall exposure, shadow areas, highlight details and so on once you’re sat in front of your computer, and take the time to get the exact results you want.

When to use it: If you’re in the habit of processing your images and card space allows, it’s a good idea to shoot in Raw images so that you always have a high-quality version.

You may not need to for general snapshots, but as Raw files contain more information than JPEGs, you’ll find that adjusting Raw files for more considered images will leave you with better-quality results than if you were to do the same to JPEGs.

There is, however, only so much information in Raw files that you can tease out of shadows and bring back in highlights, so you should aim to get things right in camera with an additional method, be it exposure compensation, bracketing or something else. Shooting Raw images should not be an excuse for laziness!

This is particularly the case with most compact cameras, whose latitude for processing Raw images is typically more limited than with cameras that offer larger sensors. The more appropriately exposed your image is to begin with the less you’ll have to adjust it in processing, and the more information your image stands to retain.

- 1

- 2

Current page: Page 1: How to always get exposure right

Next Page Page 2: How to always get exposure rightThe best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

The former editor of Digital Camera World, "Matt G" has spent the bulk of his career working in or reporting on the photographic industry. For two and a half years he worked in the trade side of the business with Jessops and Wex, serving as content marketing manager for the latter.

Switching streams he also spent five years as a journalist, where he served as technical writer and technical editor for What Digital Camera before joining DCW, taking on assignments as a freelance writer and photographer in his own right. He currently works for SmartFrame, a specialist in image-streaming technology and protection.