Four ways your meter can mess you up – don't assume your camera is always right!

We imagine our cameras are as smart as heck and for them to get the exposure right will be simple. They’re not, and it isn’t

Most of the time you can frame up a shot, press the shutter release, get a perfectly exposed image and not give your camera’s exposure metering another thought.

But then another time you might wonder why the lush, dark foliage in your woodland scene has come out pale and wishy-washy, or why the bride’s dress is gray not white, or why that contrasty sunlit urban scene has been so badly overexposed. (Did you actually ask the camera to exposure for the shadows? No, it decided that on its own.)

So don’t assume your camera metering system knows best. Often it does, sometimes it doesn’t. However powerful your camera, however many zones the metering system has, however much deep learning AI has gone into its development, it’s just a dumb machine pretending not to be.

Here are four ways it can go wrong, why, and what you can do about it.

1. It doesn’t know what you want

All digital cameras offer ‘multi-pattern’ metering or similar systems that measure light across the whole scene and use image database matching or complex algorithms to determine what the ‘best’ exposure should be.

‘Best’, in this instance, refers to what most photographers appear to have wanted most of the time in similar lighting situations in the past. It doesn’t mean it’s right, or that it reflects your intentions.

However powerful your camera, however many zones the metering system has, however much deep learning AI has gone into its development, it’s just a dumb machine pretending not to be.

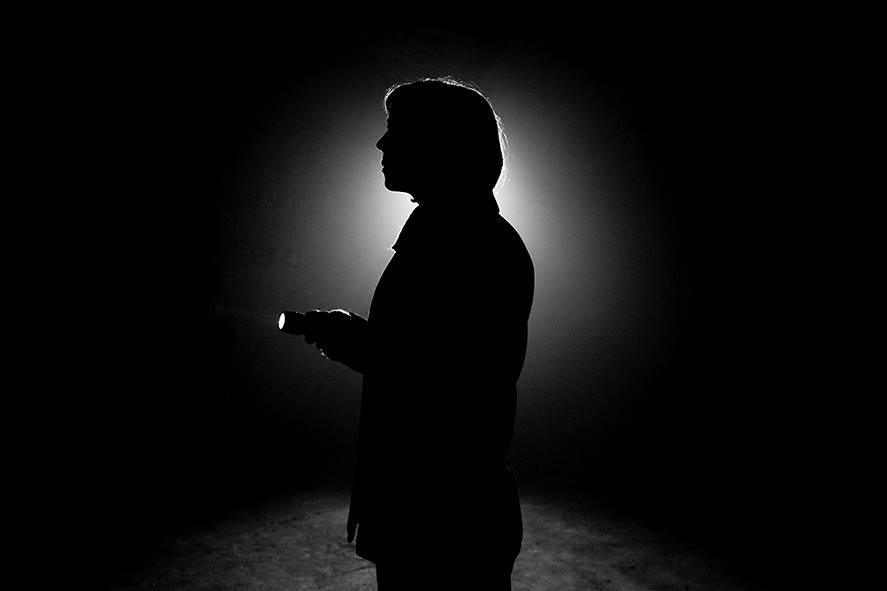

For example, when taking a portrait against the light or a bright background, do you want a silhouette or an exposure adjusted for your subject? One time it might be a silhouette that you want; another time it might be a high-key backlit portrait. The camera doesn’t know. Only you know.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

(There is an underlying suggestion that your camera can make you a better photographer by applying the learnings of others. You may prefer to apply the learnings of yourself.)

2. You don’t know what it’s going to do

Multi-pattern metering systems are complex. They make a whole series of judgements and decisions you don’t know anything about. Very often they make a really good guess that you could hardly improve on even if you measured the exposure manually.

Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they tend towards overexposure in the belief that the thing in the middle of the frame, or the largest thing in the frame, is the main subject and that’s what you want correctly exposed.

So the issue here is unpredictability. That’s why cameras still offer center-weighted and ‘averaged’ metering modes. These are cruder in the way they read the light, but much easier for photographers to second-guess.

Any engineer will tell you that to stop a system going wrong you have to understand what it's going to do. Which is difficult if nobody knows.

3. It doesn’t know light from dark

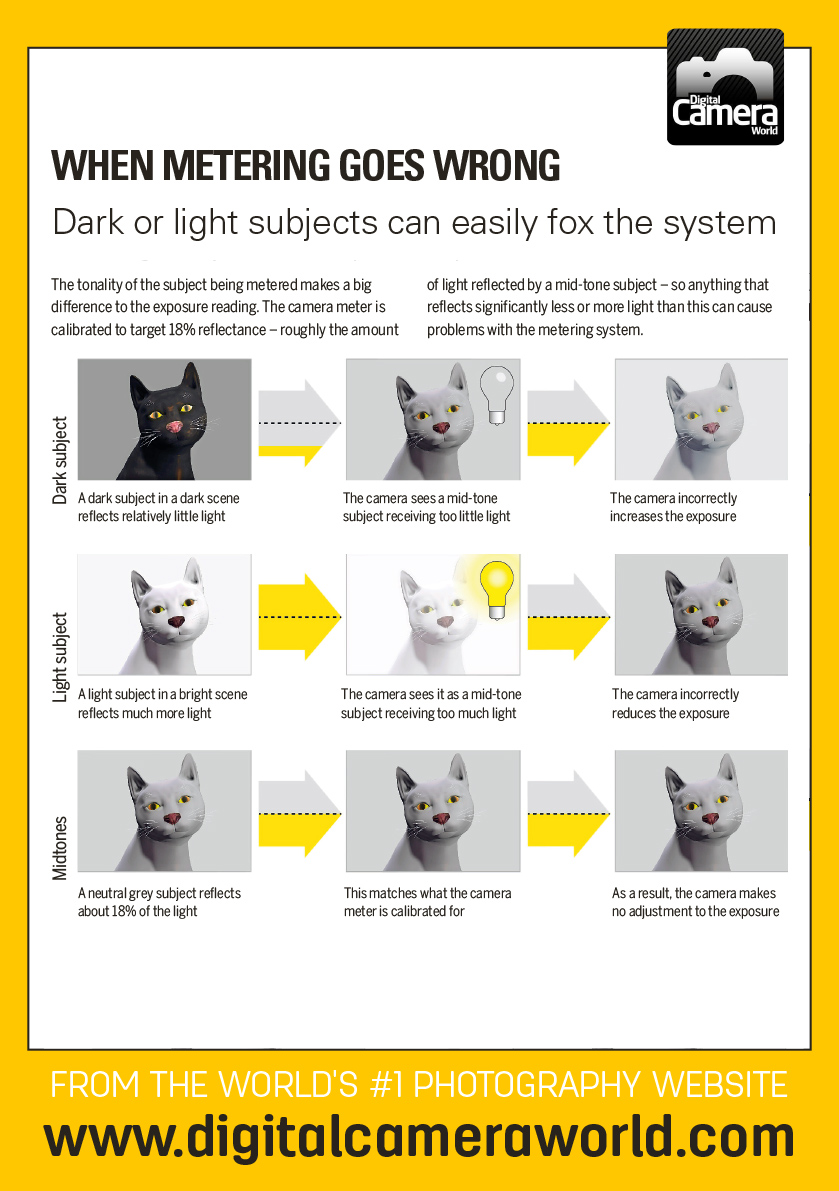

This sounds counter-intuitive. Of course the camera can measure the amount of light in the scene. However, it has no idea whether the amount of light comes from the strength of the illumination, or the innate tone of the subject.

The camera has no idea whether it’s looking at a black cat in a coal cellar or a white cat in a snowstorm. It has to assume everything is a middle sort of gray (the famous 18% gray tone) and base the exposure on that. Whatever kind of cat you’ve got, the camera will make it gray.

The solution is to use the camera’s EV compensation control – this is why they all have them. And you may be surprised at how much compensation you have to apply. For our two cat examples, it could be as much as +/-2EV either way.

4. It keeps changing its mind

You take a shot, look at it, have a little think and take another. The camera will ‘recalculate’ the exposure even when nothing has changed. You might take a dozen different pictures of the same scene from slightly different angles, and the camera’s exposure might be slightly different for each.

That’s not great if you’re trying to produce some kind of cohesive picture story, or some of the camera’s guesses are worse than others. It’s also no good if you’re shooting a panoramic ‘stitcher’, which will require a single, consistent exposure for the whole series. In studio photography with controlled lighting, the balance of light and shade might change, but the exposure should not.

This is why serious cameras have a manual exposure mode. It’s not just for purists who like to measure and set the exposure the old fashioned way. It’s for those occasions where you’ve worked out the correct exposure at the start and you don’t want the camera messing with it every time you change your framing or the angle.

So what’s the answer?

Look at the image you’ve just taken. If your camera has a histogram display, look at that too. If your picture looks too dark or too light, it’s because your camera didn’t get the exposure quite right and, if the shadows or the highlights are clipped (especially the highlights), you’ll know there’s an issue with the exposure. If you’ve got time, you can just apply a quick bit of EV compensation and shoot it again.

Alternatively, get in the habit of shooting RAW. You can typically pull back around 1EV of overexposed highlight detail from a RAW file, sometimes more, and a lot more than that from underexposed shadows.

The main thing is not to assume your camera’s exposures will always be right. And don’t be surprised if you’re constantly adjusting the EV compensation to suit your expectations and your tastes. It’s not that the camera is defective, but that your subject, or your interpretation of the scene, is too difficult for the camera. It is just a machine. You are the one with the brain.

Read more:

• Best handheld light meters

• Exposure cheat sheet

• Best cameras for beginners

Rod is an independent photography journalist and editor, and a long-standing Digital Camera World contributor, having previously worked as DCW's Group Reviews editor. Before that he has been technique editor on N-Photo, Head of Testing for the photography division and Camera Channel editor on TechRadar, as well as contributing to many other publications. He has been writing about photography technique, photo editing and digital cameras since they first appeared, and before that began his career writing about film photography. He has used and reviewed practically every interchangeable lens camera launched in the past 20 years, from entry-level DSLRs to medium format cameras, together with lenses, tripods, gimbals, light meters, camera bags and more. Rod has his own camera gear blog at fotovolo.com but also writes about photo-editing applications and techniques at lifeafterphotoshop.com