The curious story of Hitler, the fake Leica and the Russian camera forgers

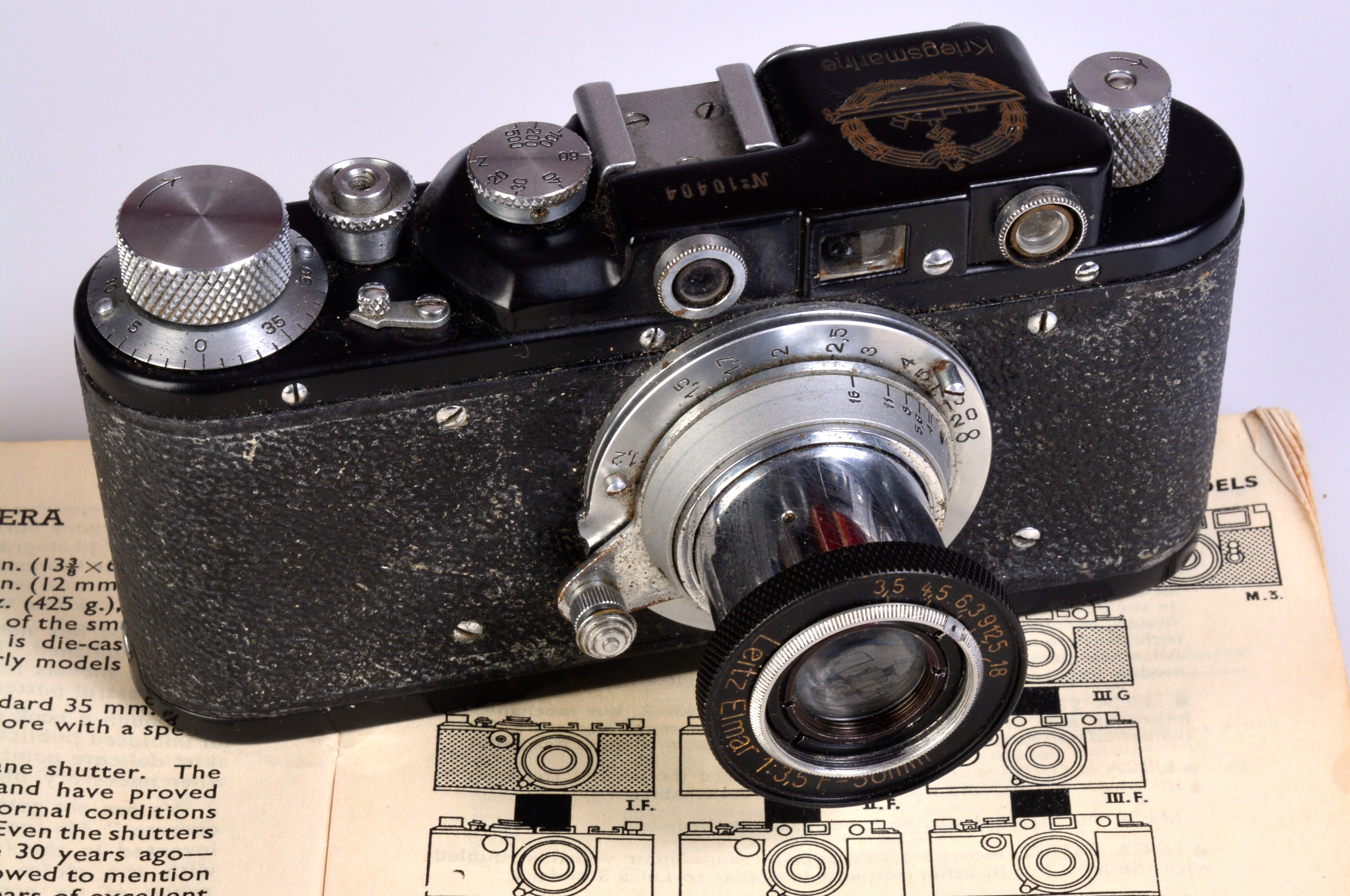

It’s not a military Leica (and not even a Leica). This is the twisted tale of the Russian counterfeit Wehrmacht Leicas

If you like a good spy story, you’ll be familiar with the operative who’s unmasked as – or confesses to being – a double agent while still concealing a third identity. It can be very hard to follow. As is the story of the counterfeit German military Leicas, because these cameras aren’t not just military Leicas, they’re not Leicas at all. See, we’re already getting caught up in double negatives.

And, if you’re familiar with the story of the Hitler diaries, you’ll know that, regardless of whether it’s in good taste or not, there’s a strong collectors market for Nazi-era memorabilia. The forger behind the Hitler diaries – Konny Kujau – reproduced a whole range of items purported to be linked to Adolf Hitler, including paintings, letters, poems and uniforms. In fact, so prolific was his output that when experts came to authenticate the handwriting in the diaries, they compared it with letters that Kujau had forged, but which had been accepted as genuine. Recently, a watch belonging to Hitler – presumably authenticated – sold at auction in the USA for US$1.1 million (around £890,000/AU$1.6 million). Not surprisingly, the sale attracted controversy, but the auction house contended, “Whether good or bad history, it must be preserved”.

There were more mercenary objectives on the minds of those who, sometime in

the mid-1990s, began forging Leica cameras from the Nazi period... the models issued to the Luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine (the German navy), the Heer (the army), and even Hitler’s personal photographers. These cameras would never fool an expert Leica collector, but they were good enough to take in somebody who thought they’d stumbled on a rare piece of WWII memorabilia.

Now, of course, Leica did make cameras for the German military, including the ultra- rare motorized 250 which held a 10-metre roll of film (giving 250 exposures) and was used by the Luftwaffe for reconnaissance. At the same time, as we now know, Ernst Leitz II was secretly finding ways for many of the Jewish workers in his employment to escape Nazi Germany and find new jobs at Leica offices in other countries, including the United Kingdom, USA and Hong Kong.

On (and off) the record

Small, lightweight and incredibly tough, the Leica 35mm rangefinder camera was ideally suited to military applications (and, indeed, was also used by a number of other forces after WWII). Most of the Wehrmacht (military) Leicas were the III series models– predominantly the more convenient to use IIIb and IIIc variants, but also the IIIcK where the ‘K’ stands for kugellager, German for ball-bearing (a reference to the shutter’s mechanism). The kugellager focal plane shutter was smoother, quieter and more reliable, and these cameras carried a ‘K’ at the end of their serial numbers.

Leica has always kept meticulous records of its camera production and so the dates of manufacture, quantities, and serial numbers of the cameras being shipped to the military are reasonably well documented (although not entirely comprehensive). This is primarily why, in the mid-to-late 1990s when numerous military ‘Leicas’ suddenly started turning up on the collector’s market with completely wrong serial numbers, suspicions were aroused. It didn’t take long to spot the fakes and identify their source – Russia – but plenty of buyers were taken in nonetheless.

The cameras of choice for the counterfeiters were the later variants of the FED 1 from the 1940s and early 1950s, and the Zorki Type 1 derived from the Ukrainian FED, but built by KMZ (the Krasnogorsk Mechanical Works) in a factory outside Moscow. It was first introduced around 1950 or ’51 and subsequently made in number running to hundreds of thousands of units.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

It was actually simply called the Zorki, although there were a number of series-one iterations through to 1956. Ironically, both the FED 1 and the Zorki 1 were direct copies of the Leica II. Consequently, the Zorki 1 and, for example, the later Type 9 and Type 10 versions of the FED 1 from the 1940s are virtually identical and very hard to tell apart when tricked up to look like something else. In fact, there was a transitional model called the FED Zorki that subsequently evolved into the Zorki 1A and then, with some minor modifications, the 1B. The most notable modification was to the shutter button and its collar which allowed for the fitting of a cable release. This is the key identifying factor for the fake Leica illustrated here, along with several aspects of the lens’s design – including a surface coating – which indicate this is a Zorki 1B from somewhere around 1953.

The I is not a III (or even a II)

Unlike the camera it was meant to represent, the Zorki 1B wasn’t especially reliable, particularly as it was necessary to wind on the film (i.e. recocking the shutter) before changing the shutter speed setting, an idiosyncrasy that continued through

to the last-of-the-line Zorki 4K... which, incidentally, came after the Zorki 5 and 6 models. Failing to wind on before changing the shutter speed could break the setting pin, rendering the dial useless. As with all Soviet-era 35mm RF cameras, the shutter speed dial rotates as the shutter is released and then also as the film is wound on, something that didn’t happen on a Leica.

As was common at the time, film wind-on is via a knob and the Zorki I directly copied Leica II’s horizontal-travel focal plane shutter with cloth curtains and a speed range of 1/20 to 1/500 second, plus ‘Z’. The ‘Z’ stands for zeit, the German word for ‘time’ and is, of course, the ‘B’ or bulb timer setting. Focusing is via a coupled coincident-type rangefinder, but the viewfinder is separate.

Film loading is through the baseplate as is the case on all Leica’s 35mm rangefinder models, and the lens mount is Leica’s 39mm diameter screwthread fitting.

Introduced in 1932, the Leica II was actually Leica’s first model with rangefinder focusing and remained in production after the improved model III debuted in 1933.

As already noted, the Leica II and the Zorki 1 look very similar with only a slight variation in the design of the viewfinder window being particularly obvious if you know what you’re looking at. However, the visual differences with the III series models are much easier to see, most notably the addition of a second shutter speed dial on the front panel for setting slower speeds from one second to 1/20 second, plus a ‘T’ option to supplement the main dial’s ‘Z’ timer setting. Furthermore, on the IIIb (1938) – and hence also the IIIc (1940) – the rangefinder eyepieces were moved much closer together and the focusing adjustment was relocated from around the lens mount to below the film rewind knob.

Exposure and exposed

So, it’s not all that hard to spot a Zorki 1B masquerading as either a Leica IIIb or a IIIc, but the forgers of the camera featured here were particularly ambitious since it’s thought that only one batch of 49 IIIc models was ever officially delivered to the Kriegsmarine. This took place in 1942.

If ever a fake military Leica could be more easily exposed, this has to be it, especially as there are much better attempts based on real Leica IIIc bodies and lenses with very precise engravings. That said, the markings on this Zorki ‘Kriegsmarine’ Leica are high-quality too, but nothing else gets close, including the serial number that’s

only five digits instead of six. The lens is marked “Leitz Elmar 1:3,5 F=50mm” which is certainly correct in style, but the design of the aperture setting tab indicates that it’s the Industar-22 35mm f/3.5 lens that was common on the Zorki 1... the other giveaway being that the focusing tab locks a little beyond the infinity setting (which makes it useless for calibrating the rangefinder).

The push-on lens cap is engraved with the Reichsadler (Imperial Eagle) and swastika insignia which was particularly used by the Kriegsmarine between 1935 and 1945. The camera body’s markings depict the Reichsadler with a laurel wreath and the profile of a U-boat.

The double irony is that, following the end of the war, quite a number of

the genuine Wehrmacht Leicas had their markings erased to hide any links with the disgraceful and disgraced Nazi regime. Another irony is that the Russian fakes from the late 1990s are now collectible in themselves. It’s not known how many were made – there certainly would have been a plentiful supply of very cheap ‘base’ cameras – but the fakes continue to be worth many, many times more.

Funnily enough, it’s actually a pretty nice camera to use and, of course, not having had any actual ties with the Nazi regime, comes largely guilt-free... as long as the dubious practices of Russian counterfeiters don’t worry you too much.

Best Leica cameras

Best Leica M lenses

Best film cameras in 2023

Paul has been writing about cameras, photography and photographers for 40 years. He joined Australian Camera as an editorial assistant in 1982, subsequently becoming the magazine’s technical editor, and has been editor since 1998. He is also the editor of sister publication ProPhoto, a position he has held since 1989. In 2011, Paul was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institute Of Australian Photography (AIPP) in recognition of his long-term contribution to the Australian photo industry. Outside of his magazine work, he is the editor of the Contemporary Photographers: Australia series of monographs which document the lives of Australia’s most important photographers.