The cleverest camera I ever owned was also definitely the worst!

The Lytro camera told me I could change the focus afterward, and I was lured in by the tech bubble

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How was I ever so stupid? Sure, I was young. Well, younger. But surely not young enough to believe that the history of optics could be wiped out by a camera the size and shape of a candy bar?

Well (as I shift uncomfortably in my seat) I can only say I visited a lot of photo trade shows. Digital hadn't long crossed the point it was truly useful for professional photographers, and there were plenty who still hadn't admitted it. In those heady days, it's possible I didn't do the best of sorting the sensible from the clearly fanciful.

The Lytro promised to change photography

All of which is a roundabout way of excusing myself for telling my boss we needed to get on board this Lytro train I was hearing so much about. The Lytro was – sort of – a light field camera, which meant that you could change the focus of the image AFTER you took the picture. Beat that, RAW file!

Article continues belowThe idea of recording the light field is that the direction of the photos is recorded as they hit the image sensor. This, in turn, makes it possible to assemble a 3D image (and 3D movies were also still a thing in 2009). The practical upshot is that you could tap on the screen to re-focus the picture after it was taken, and even more possibilities seemed only a firmware update away.

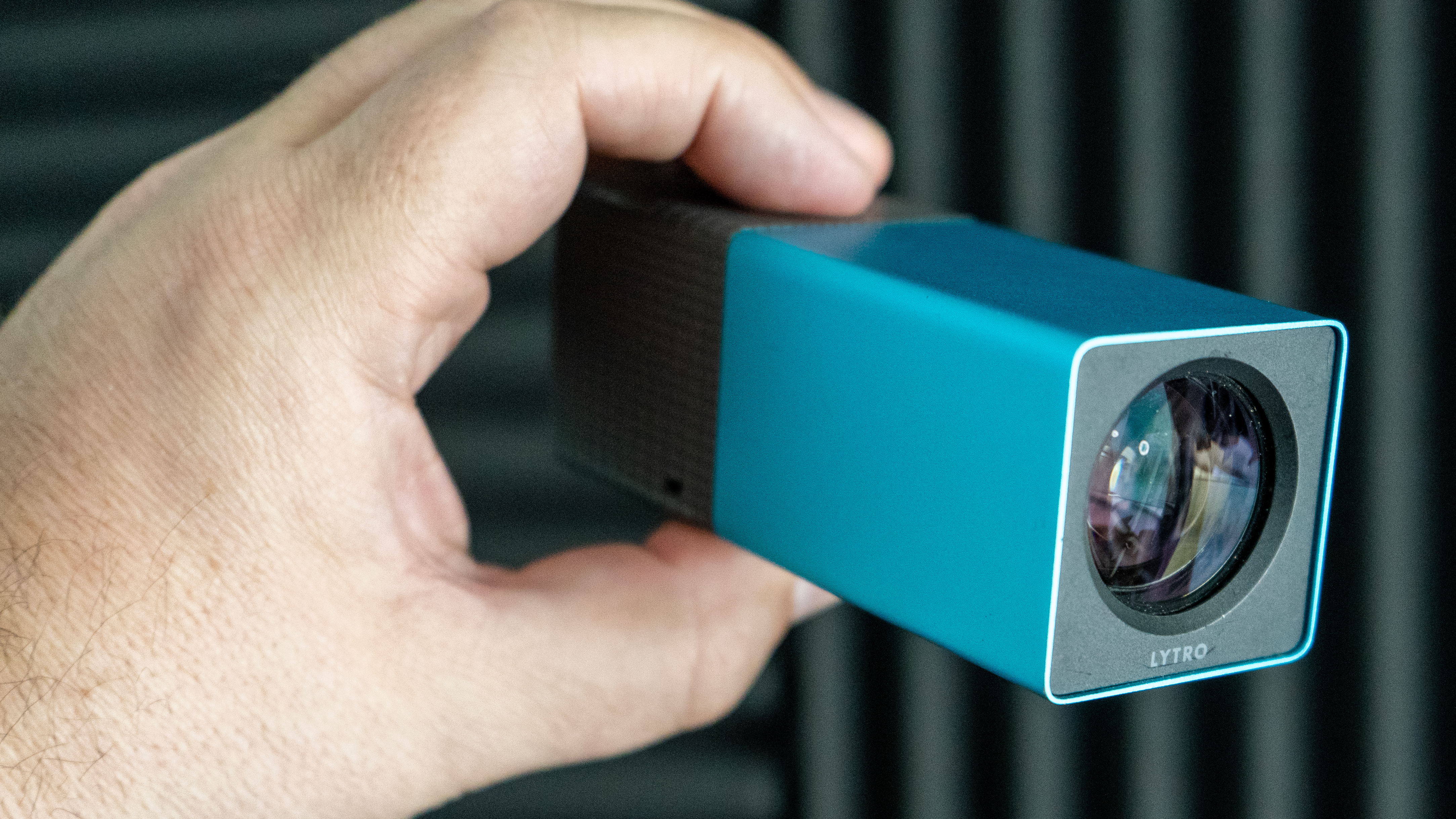

But, in practice, things were less revolutionary. For a start, the usability was dubious at best. The consumer Lytro was a rectangular barrel, and clicking the rubber-covered shutter – recessed in the grip end – tended to cause the whole device to move.

The camera claimed to capture images of '11 megarays,' which sounded a lot at the time – the 21-megapixel Canon EOS 5D Mk III came out in the same year, but the megarays? That must be revolutionary, right? Well... no, as it turned out they equated to a 1.2 megapixel image once converted to pixels. A lot less, even, than the year's new iPhone, the iPhone 5, which boasted 8 megapixels.

A 1.2 megapixel image didn't have that much sharpness to it anyway, so the focus blurring effect often felt a bit forced, which meant that – even when there was an iPhone app to refocus the images with – it was just boring after a few goes. It was so straightforward and offered so few creative possibilities there certainly didn't need to be a book about it, so I definitely should have left it alone!

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

To get the best of the Lytro you needed to place two or more subjects, near to and far from the lens. No more playing with the field of view, though, before resolution became your enemy. That's not a lot of creative potential.

Worst of all, now the company – and app – is gone, the 128 x 128 pixel touchscreen or an archived version of the Windows app is now the only way to view images. The Mac one seems to have been defeated by a security update to the OS. Failing that, the camera's built-in memory is the only way I can store images, so it's one in, one out!

What happened to Lytro?

At least I never signed off the acquisition of the subsequent 'pro' Lytro Illum, a 40 megaray camera that looked more SLR-like, had a 30-250mm 8.3x optical zoom, and a more useful 4-inch touchscreen.

But boy did Lytro not give up. After that came the Lytro Immerge, an end-to-end system using light field capture tech for VR content, straight onto a portable rack-mount server, and at NAB 2016 the firm wowed crowds with an enormous cinema-capable camera which boasted an imaging sensor of about half a meter, or 19 inches.

In its fairly short life, the company burned through at least $140 million (some say over $200 million). The company was wound up in March 2018 with a lot of the staff moving on to Google and, apparently, an unfinished 40K cinema camera left in the dirt.

If you're brave enough, though, we've still seen them listed for sale, but don't expect support!

With over 20 years of expertise as a tech journalist, Adam brings a wealth of knowledge across a vast number of product categories, including timelapse cameras, home security cameras, NVR cameras, photography books, webcams, 3D printers and 3D scanners, borescopes, radar detectors… and, above all, drones.

Adam is our resident expert on all aspects of camera drones and drone photography, from buying guides on the best choices for aerial photographers of all ability levels to the latest rules and regulations on piloting drones.

He is the author of a number of books including The Complete Guide to Drones, The Smart Smart Home Handbook, 101 Tips for DSLR Video and The Drone Pilot's Handbook.