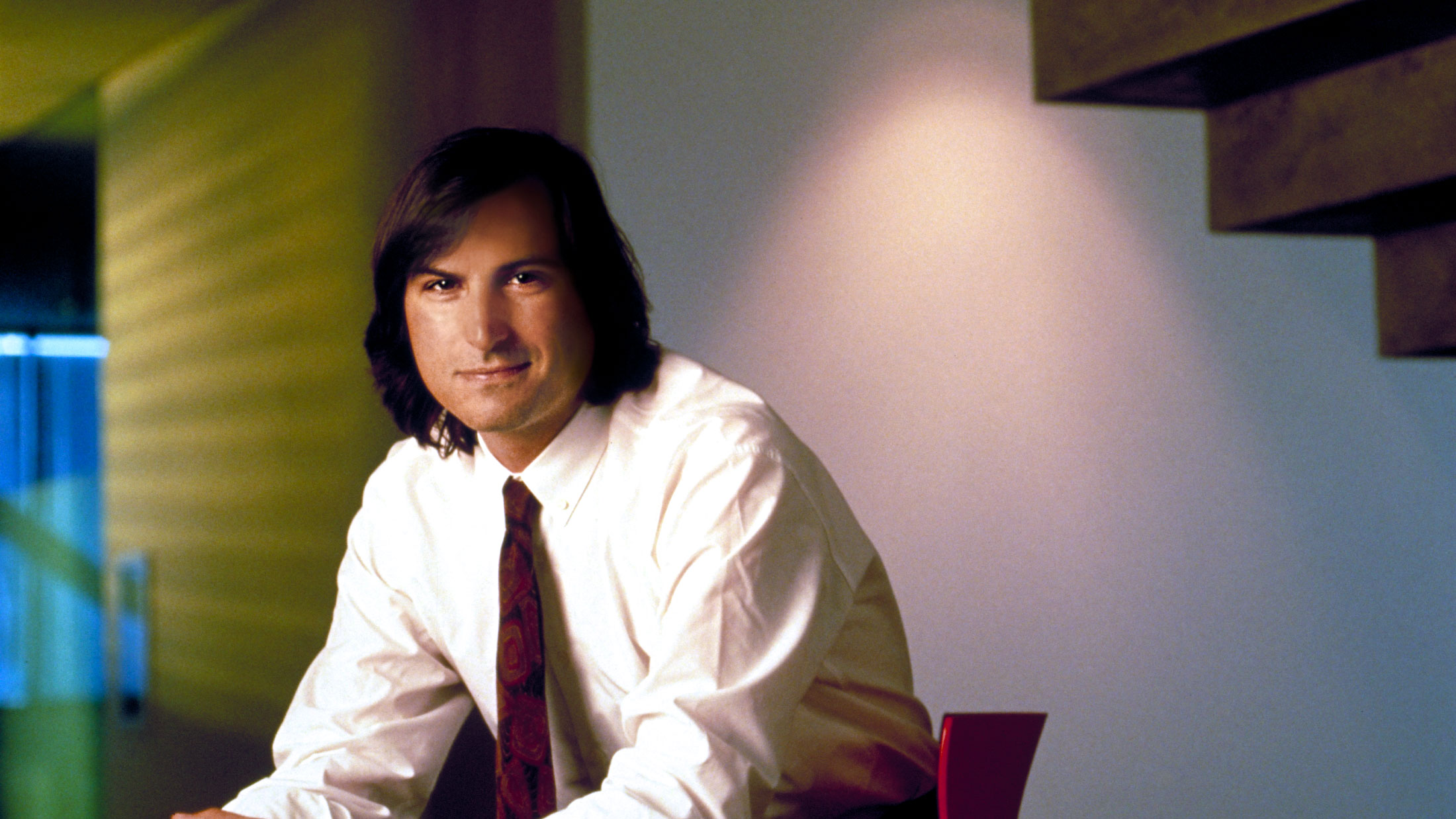

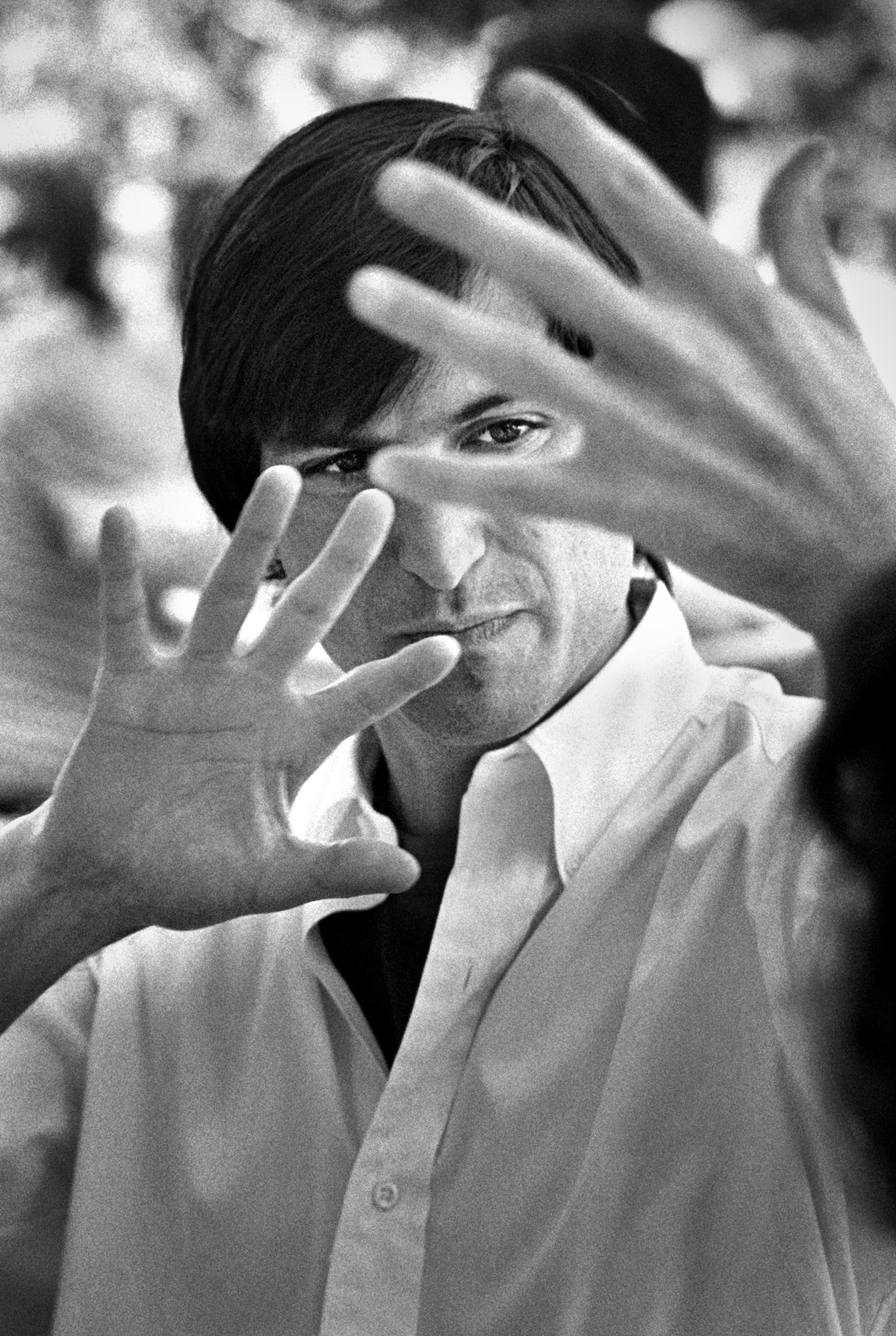

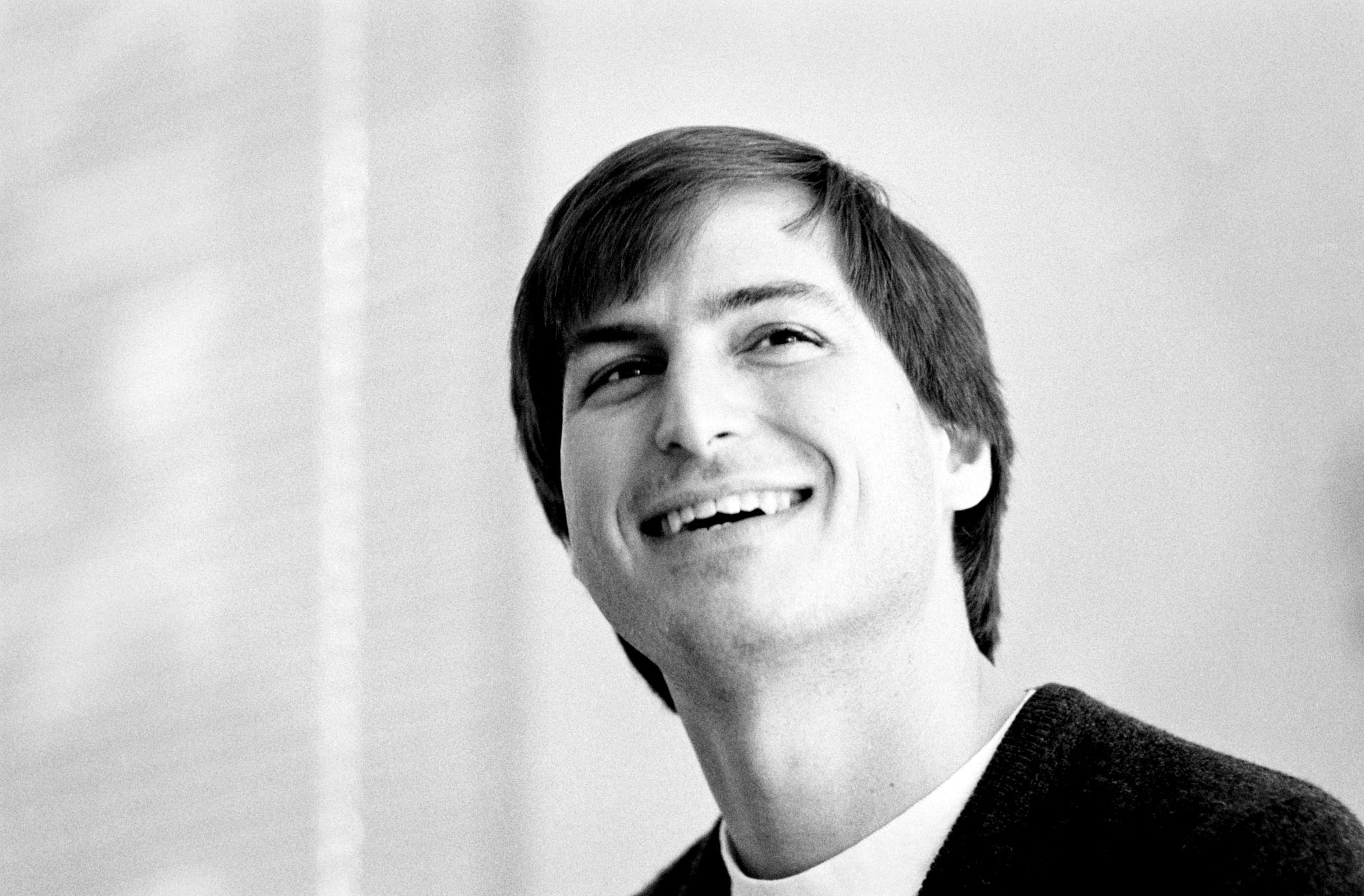

Rare portraits of Steve Jobs show off another side to the genius

From presidents, actors and tech pioneers to orphans and earthquake survivors, American photographer Doug Menuez has spent 40 years photographing stories about our shared humanity

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Born in Texas in 1957, Doug Menuez played in a blues band in his teenage years before training as a photographer at the San Francisco Art Institute followed by San Francisco State University. Since the late 1970s, his career has encompassed a range of genres, from photojournalism and documentary photography to film-making and commercial projects.

Menuez’s work has been exhibited around the world and his books include Fearless Genius: The Digital Revolution in Silicon Valley 1985-2000, Heaven, Earth, Tequila: Un Viaje al Corazón de Mexico, Fifteen Seconds: The Great California Earthquake of 1989, and Transcendent Spirit: The Orphans of Uganda. He now lives in upstate New York.

To find out more, visit:

www.menuez.com

There are 7.8 billion people living on Planet Earth, so when American photographer Doug Menuez outlines his area of interest as “humanity”, he’s not short of subject matter.

In his 40 years as a photojournalist, documentary photographer and director, Menuez has captured a diverse cross-section of humanity, from leaders and luminaries, including President Clinton, Mother Teresa, and Jane Goodall, to A-list actors such as Robert Redford and Cate Blanchett, through to scientists, astronauts, and drug dealers.

From the mid-1980s, Menuez spent three years documenting Steve Jobs and his team at NeXT, and 15 years documenting the digital revolution, many of his images collected together in his book Fearless Genius. Menuez’s photos have appeared in Time, LIFE, Newsweek, The Washington Post and many more publications. Assignments to capture stories, including the AIDS crisis, presidential campaigns, Super Bowls, the Ethiopian famine and the Oakland drug wars, have taken him around the world, from the North Pole to the Sahara, Vietnam to Mexico.

His work has helped raise money for orphans in Uganda and victims of the San Francisco earthquake. He has worked on ad campaigns and commercial projects for global brands, such as Leica, Coca Cola and Microsoft.

It’s a far cry from the life that might have been: Menuez was a blues musician in his early years, quitting the rising band to make the leap into photojournalism.

Here, he talks to Graeme Green about meeting Steve Jobs, escaping gunfire, NFTs and his latest projects.

Your work is incredibly varied. When people ask what kind of photographer

you are, what do you say?

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

I’m interested in human beings, what they do and why they do them. That leads to telling stories about human beings and their lives, and creating connections between subcultures and larger cultures. It’s really about the human experience and shared humanity.

It’s driven by something I realised I did early on, which is figuring out who I am and my place in the world. It’s curiosity about where we are, why we’re here… that sort of existential crisis. So, I picked up a camera.

You spent some time with Steve Jobs. What was he like to work with?

He was inspired and incredibly passionate. He was constantly learning, and a great leader. If he believed in an idea, he could convince everybody to follow him to Mars. We tend to put him as either this iconic ‘genius’ or a ‘jerk’. But Steve was complicated. He could be incredibly sweet and thoughtful, but primarily what he was about was solving the mission.

He had a flaw where he could cross the line and attack you personally, but this was about getting you to do something he wanted, like getting an engineer to do something they thought was impossible. He was driven by a need to trust. In start-ups, any decision could wreck a company. There’s so much money and pressure. He wanted people who would stand up to him and fight back.

Could you see where our lives were going in terms of a technology revolution?

In some cases, yes. I had engineers sit me down and show me something they were working on. In New York, none of my editors at magazines thought they would need or own a computer. The people in Silicon Valley could see the potential of applications they were creating to change people’s lives.

Steve gave me a glimpse into a world of potential change and a world that was to come. My friends thought I was nuts wanting to photograph people staring into computer screens when I could be covering conflicts in Africa. But once I saw what these people were going to do, that kept me hooked.

What characterised that late 1990s period and the people you met in Silicon Valley?

The people I documented back then were idealists. They really did have an impulse to improve human life. When Wall Street got involved, short-term thinking took over and there was a shift to an unsustainable gold rush that took away a lot of that noble cause. It became really corrupted.

I’m looking to this next generation to see if they’re going to have that idealism and fight for this dream to improve our lives. The problem is, can they even get funding for hard science problems, like climate change? It’s hard to get funding for anything apart from apps and games right now.

You have photographed US presidents, including Bill Clinton and George Bush Senior. Is that a high-pressure situation?

Yes. You have the Secret Service there, a lot of preparation and clearance, and you feel the weight of history. I’m always amazed when I interact with someone who is making history. You just have to put the terror and fear of what can go wrong away and lock it up.

I loved meeting the Bushes. Politically, I’m a progressive and a staunch Democrat, but in my line of work, you get to see people at a human level, aside from the politics.

I had an idea to shoot George Bush looking out of the window. The editorial team and the Secret Service were getting nervous about the idea of moving him. No one would help. So he said “Lift me up, Doug”, and I lifted the former President, put him in the wheelchair and wheeled him into position.

He was humble about it and said, “You’re getting very artsy, aren’t you, Doug?” Barbara leaned over and kissed him at the last minute, which made for a great photograph.

You also met Mother Teresa. What was your encounter with her like?

I was only 22 when I met her. This was her first visit to the US. I saw the scrum of media in front of the church waiting for a press conference. I thought: what can I find that would be unique and different to tell the story?

Somebody nearby was waiting at the foot of a chapel, 200 yards from where all the press were, so I sneaked into the church and looked through the curtains as she was praying in a pew. I took some pictures, then waited. As she came down the stairs, she gave me a beautiful smile and some kids ran up to her. That was my moment. It was different from what everyone else got and it ran on the cover of The Washington Post.

It reinforced the idea that you have to get beyond the obvious. You need to keep looking for ideas behind the scenes you’re assigned to.

Of all the famous actors you have photographed, which is the one that has made the greatest impression on you?

Charlize Theron. We were in the Democratic Republic of Congo, standing in the mud. She was in her bare feet and she asked me to come over to her. She’d had a beautiful pedicure with a lovely caramel nail polish. Her bare feet were getting ruined by the rain and mud. She’d just come from the Oscars, and she thought this was hilarious.

She was tough as nails. I just thought of her as an actor and a kamikaze crazy dedicated to the cause. But she turned out to be the real deal. She was running a rape crisis centre in the eastern DR Congo and working on education and AIDS education in South Africa. When you spend three days with somebody in the jungle, you see what they’re made of and she struck me as a tremendous human being.

What impact did covering the 1989 San Francisco earthquake have on you?

When you go into these crises, you could react emotionally, but you control that. You know you have a job to do and I just did it. I rushed to get a helicopter and spent two days flying, circling the disaster scene. I was getting assignments from Time magazine and USA Today. But later, I did get out on the streets and saw beautiful neighbourhoods with collapsed houses and people digging through the rubble and it was heartbreaking.

Years later, I couldn’t shoot that anymore. I was doing forest fires or whatever, shooting the survivors. It got to the point I didn’t want to invade their privacy anymore. I wanted to do documentary work where I could engage with my subjects in an equitable way.

Doug is currently offering Heaven, Earth, Tequila book in softcover with 20 percent going to NYCSALT photo education program for underserved kids. For more information, visit Doug's book collection.

Your photography and books have helped raise money, including for the victims of the San Francisco earthquake and AIDS orphans in Uganda. Is it satisfying to work on projects that make a clear difference?

With the earthquake, we raised more than $500,000. We all want to make a photo that’s going to improve the world or change the world. Every photojournalist and documentary photographer I know believes that by bringing their camera into a difficult situation, they might be able to bring light to injustice. I’ve covered famine and poverty, it’s part of giving people the facts, but almost nothing ever changes. So, it’s a great satisfaction to do a project that raises money and you can give the money directly to those in need.

Have you had any close calls on international assignments?

I covered an expedition to the North Pole back in 1994. At the end of the Cold War, a friend of mine leased a Russian icebreaker and I got an assignment to cover it. Because it’s an atomic ship, there’s security, including armed guards, one of them with a shotgun.

One day, they were laughing and dragged me out onto a decrepit cargo helicopter. There were women on board and a pilot, all drinking clear liquid, which turned out to be de-icing fluid. We went off on a crazy excursion, got lost in an Arctic storm and landed on the ice. All of a sudden, the fog cleared and the ship was bearing down on us. We took off, just as the icebreaker nearly hit. We could have died.

The next day, we all went out across a glacier and landed on Novaya Zemlya, a highly radioactive nuclear testing ground for the Soviets. We landed near a group of Inuit reindeer herders. The two armed guards wanted to shoot a reindeer and demanded I bring vodka. We ended up negotiating with the herders. The guys shot one of the reindeer with a rifle the Inuit had loaned to them. They skinned the reindeer on the tundra. One of the guys put the bloody reindeer on his shoulder and we started hiking back to the helicopter.

Suddenly, I started hearing shots. The Inuit thought the Russians were stealing the rifle they had lent them, whereas they’d left it out on the tundra. They ran, threw the deer on the helicopter, bullets pinging off the helicopter. They dragged me in and we flew away.

We landed in another part of the island, right in an old Russian gulag with a barbed-wire fence. There was a human skull next to the fence. They set up a barbecue to cook the reindeer in this abandoned gulag. It was an insane experience.

Has your work changed over the years?

I haven’t changed much. I’m still fascinated by the same thing I was when I started – people and the world around me.

We moved to a little town, Kingston, in upstate New York a few years ago. So much has changed there. There are so many artists, people moving up from New York City. One issue with that is real estate developers follow and you get gentrification. We’re in a diverse community with a wide economic disparity.

I was curious about this town, so I would meet people, photograph them and interview them. It’s grown into a really satisfying project. It’s like going full circle to being a kid and shooting photos near where I lived.

What else are you working on currently?

I started directing more last year, doing short films. We’re hoping to do a TV series on Silicon Valley, based on my Fearless Genius book.

You’ve looked at tech innovations before. What are your thoughts on NFTs?

It’s a growing market. There will be ups and downs, but I’m positive it will stay. I know a lot of people in the art world look down their noses at it as wacky digital art. But we’re already seeing classic photojournalist images and fine art selling. It’s moving and changing, I’m just trying to figure out how to get into it.

Do you have any regrets about quitting your blues band?

If you’d asked me a couple of years ago, I’d have said, ‘No way’, but I’m starting to have regrets. I’d have liked to have done both music and photography, but I felt I had to focus. It takes effort to do music, you have to practice. I’ve had a full life so I can’t say I regret the past, but I want to start playing music again.

Read more:

Photography tips

Top ways to use The Photography Show to boost your business

World-class Super Stage lineup revealed for The Photography Show