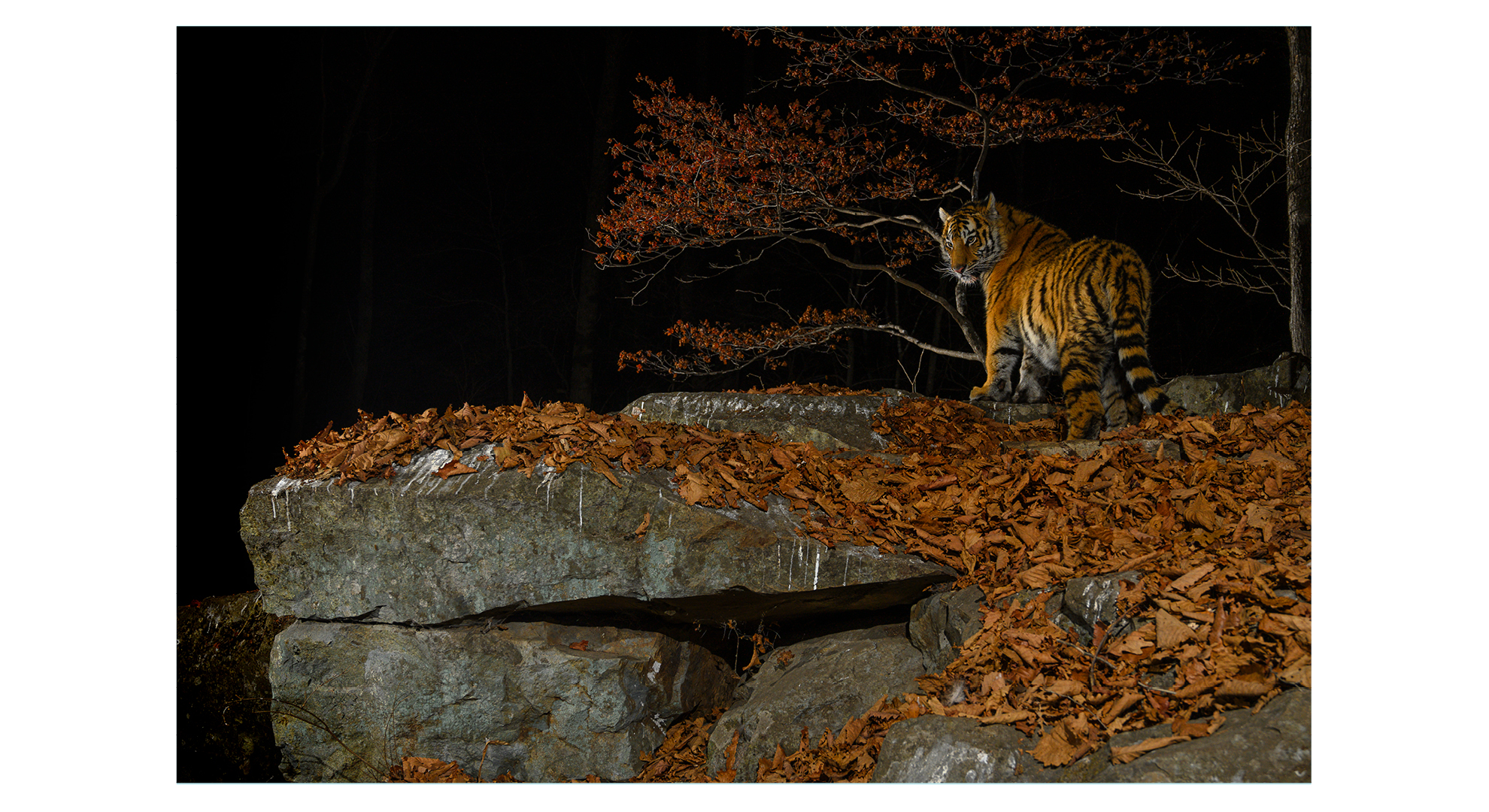

It took me 11 months using a camera trap to win Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Leading wildlife photographer Sergey Gorshkov had to use camera triggers and be very patient to get this amazing Siberian tiger shot

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Esteemed wildlife photographer Sergey Gorshkov was crowned Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2020 for his photo of a Siberian tiger hugging a tree.

Captured in the far east of Russia using a camera trap which had been in situ for 11 months, Gorshkov is passionate about tigers and conservation.

He was therefore a natural choice to be a member of the judging panel for the Remembering Tigers and Digital Camera World magazine photo competition, held early in 2024, where readers submitted their best photographs of tigers to be in with a chance of appearing in the 'Remembering Tigers' book.

The resulting coffee table book is the ninth in the Remembering Wildlife series, which since 2009 has raised $1.5m/£1.17m for conservation projects.

It features 88 stunning color images from some of the world’s top wildlife photographers, including Gorshkov.

Ahead of the launch of 'Remembering Tigers', we caught up with Gorshkov to discover more about his photography, tigers… and that winning image.

Why do you use camera traps?

When I first picked up a camera, I wanted the animals to fill the entire frame, so telephoto lenses were my main assistants during shooting. But over the years, my view has changed.

When shooting animals in the environment, it is not the object that is important, but what is around it. The object is only a small addition and decoration of the frame.

I love watching wild animals and prefer to choose the moment when I need to press the shutter button. Tigers are so rare that it is very, very difficult to see them and even more beautifully shoot them in the wild, and now, after several years of work in the Primorsky Territory, I can confidently say it is almost impossible.

Therefore, I decided to try to shoot hidden cameras. Later I realized that this was the only right solution for shooting the Amur tiger; there is simply no other way.

Professional hidden cameras installed in the forest automatically capture footage from the life of the inhabitants, so with their help we can see the real, non-staged behavior of wild animals.

Of course, using hidden cameras is not a quick way to get good photographs. It takes time, patience and skill and then you will be rewarded and the hard work will pay off.

Which camera trap setup did you use?

At the end of 2018, I bought four Cognisys starter kits with active passive sensors and tested them on seals for a week at -25°C. In January 2019 I went to the Borisov Plateau with these kits.

There were plenty of things I didn’t know about setting up and working the Cognisys camera traps, but gradually I mastered and even improved the techniques.

Over time, 30 Cognisys boxes appeared in my setup, and a sufficient number of active and passive sensors.

The Cognisys system allows you to use professional cameras, and Nikon kindly provided me with new Z7 mirrorless cameras and the necessary lenses.

Why did you choose mirrorless cameras?

Simple – animals have very fine hearing and the moment a shutter is fired, they turn their heads and look directly into the lens. I don’t like shots like this because the animals look unnatural and tense.

The main reason I started using Nikon Z7 mirrorless cameras is that there is no mirror, so at the time of shooting they work silently and don’t disturb the animals.

How did you capture the image that won Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2020?

Trailing a tigress in the far east of Russia in January 2019 led us to a huge fir tree, which may have been several hundred years old.

We were stopped by a pungent smell; when we looked closely, we noticed marks left on the trunk from the claws of bears and tigers, and wool hairs of various visitors stuck to the resin.

By leaving urinary marks on the tree, leopards and tigers convey a variety of messages to the inhabitants of this section of the forest, so I installed a hidden camera to try to film what was happening there.

Why did it take 11 months to get the shot?

After the first Nikon camera box was installed in January 2019, the visitors who approached this huge fir tree every day were watched and filmed.

I installed a Browning photo trap next to it, in case something went wrong. Two months later, I returned. All this time I constantly thought about what was going on at the fir tree and dreamed that the memory card would be full of tigers and leopards.

I couldn't wait to see what was in the sensor's area of operation. I turned on the screen, started browsing, flipping, flipping, flipping, and complete disappointment – there were 2,500 false positives in two weeks. Not a single shot of a leopard.

This meant that for another month and two weeks the hidden camera stood in vain, and even if a tiger or leopard or any other animal came, the camera couldn’t record everything due to a lack of free space on the memory card.

My brain was exploding from hopelessness. It was terrible; so much time had been lost and it's possible that at that time the beast was approaching the fir tree.

Why did the sensor fire and send false signals to the camera? I took the captured memory card for analysis, changed it to an empty one, checked the battery charge status and left.

When we returned to our winter quarters, we analysed the footage. The first mistake in the setup was that my cameras were set to work around the clock and were ready to shoot at any time of the day.

The second mistake is that due to my lack of experience, I set the PIR [passive infrared] sensor to maximum sensitivity in the hope of not missing an animal appearing. The PIR sensor was triggered by almost all movement of branches, a running shadow, and small birds.

Returning a day later, I reduced the sensitivity by half, adjusted the shooting settings to daytime mode only and flew home again. In June, the same result awaited me – the memory card had clogged up in two weeks.

I contacted the sensor manufacturer, explained the problem to them, and a month later, at my request, they changed the sensitivity of the PIR sensors.

After downloading the updates, I flashed all my PIR sensors. Now the camera was shooting a lot of interesting things, but these were not the shots I dreamed of.

I am persistent and knew that sooner or later my day would come and it came – not even a day, but a week. I visited the trap box in November and noticed a fresh tiger trail in the snow leading to a fir tree.

When I started watching the footage, my heart was pounding; when you open the lid of the box, you don’t know what the result will be. Months of waiting, preparation, failures, and now bang and pop.

There was an animal in almost every frame: a female Far Eastern leopard came to the fir a couple of times and at least three different Siberian tigers, badgers, foxes and even squirrels… the ‘Indian’ marten kharza climbed a tree to examine the sensor better and leave her scent on top of the tiger’s.

But the best shot was a tigress hugging a fir tree – we had lost her in April and thought she had either been killed by poachers or had changed her territory. The tigress had returned, though, and here she was in the picture!

I forgot I had entered Wildlife Photographer of the Year but the organisers wrote to me inviting me to the awards ceremony – there was not a hint of victory in the letter.

I was watching it online in October 2020 [due to Covid 19, there was no physical event] and didn’t believe it when the Duchess of Cambridge said my name.

It was a long, hard but very interesting journey, but I’m not going to hang my camera up on the wall. I enjoyed the victory for a few hours and have continued my photography – I want to shoot, shoot and shoot!

A self-taught photographer of the natural world, Sergey Gorshkov won the prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition in 2020, for his photo of a tiger hugging a tree in his native Russia. Passionate about conservation, Gorshkov chooses to photograph only subjects that profoundly affect him.

A version of this interview appears in the November 2024 issue of Digital Camera World magazine – see below for details of how to subscribe.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

All subscribers to Digital Camera World magazine can now access digital back issues dating from 2009 (when using iOS) or 2012 (when using the Pocketmags Magazine Newsstand app or the Pocketmags website).

Digital Camera World is the world’s favorite photography magazine and is packed with the latest news, reviews, tutorials, expert buying advice, tips and inspiring images. Plus, every issue comes with a selection of bonus gifts of interest to photographers of all abilities.

Niall is the editor of Digital Camera Magazine, and has been shooting on interchangeable lens cameras for over 20 years, and on various point-and-shoot models for years before that.

Working alongside professional photographers for many years as a jobbing journalist gave Niall the curiosity to also start working on the other side of the lens. These days his favored shooting subjects include wildlife, travel and street photography, and he also enjoys dabbling with studio still life.

On the site you will see him writing photographer profiles, asking questions for Q&As and interviews, reporting on the latest and most noteworthy photography competitions, and sharing his knowledge on website building.