Lately, I've been noticing something rather peculiar happening in the publishing world – and it's got me genuinely excited. In 1999, there were roughly 100 publishers worldwide dealing with photography books. Today? That figure has mushroomed to nearly 500.

Walk into any decent photography bookshop and you'll find shelves groaning under the weight of titles. Whether it's small presses like Void or bigger names like Mack, they're all shifting some serious units.

In short, photography books are back. Not just back, but cool again. But why?

The vinyl parallel

You may have noticed that vinyl records made a big comeback a few years back. Now even my mate Dave, who exclusively listened to Spotify for a decade, has started banging on about the "warmth" of his limited-edition pressing of whatever obscure post-punk band he's discovered this week.

So you could say photography books have been having their own "vinyl moment". And in fact, the parallels are obvious once you start looking for them.

Both types of media were supposedly killed off by digital innovation. Both were dismissed as obsolete, bulky and unnecessary. And both have clawed their way back to relevance; not despite their physical limitations, but because of them.

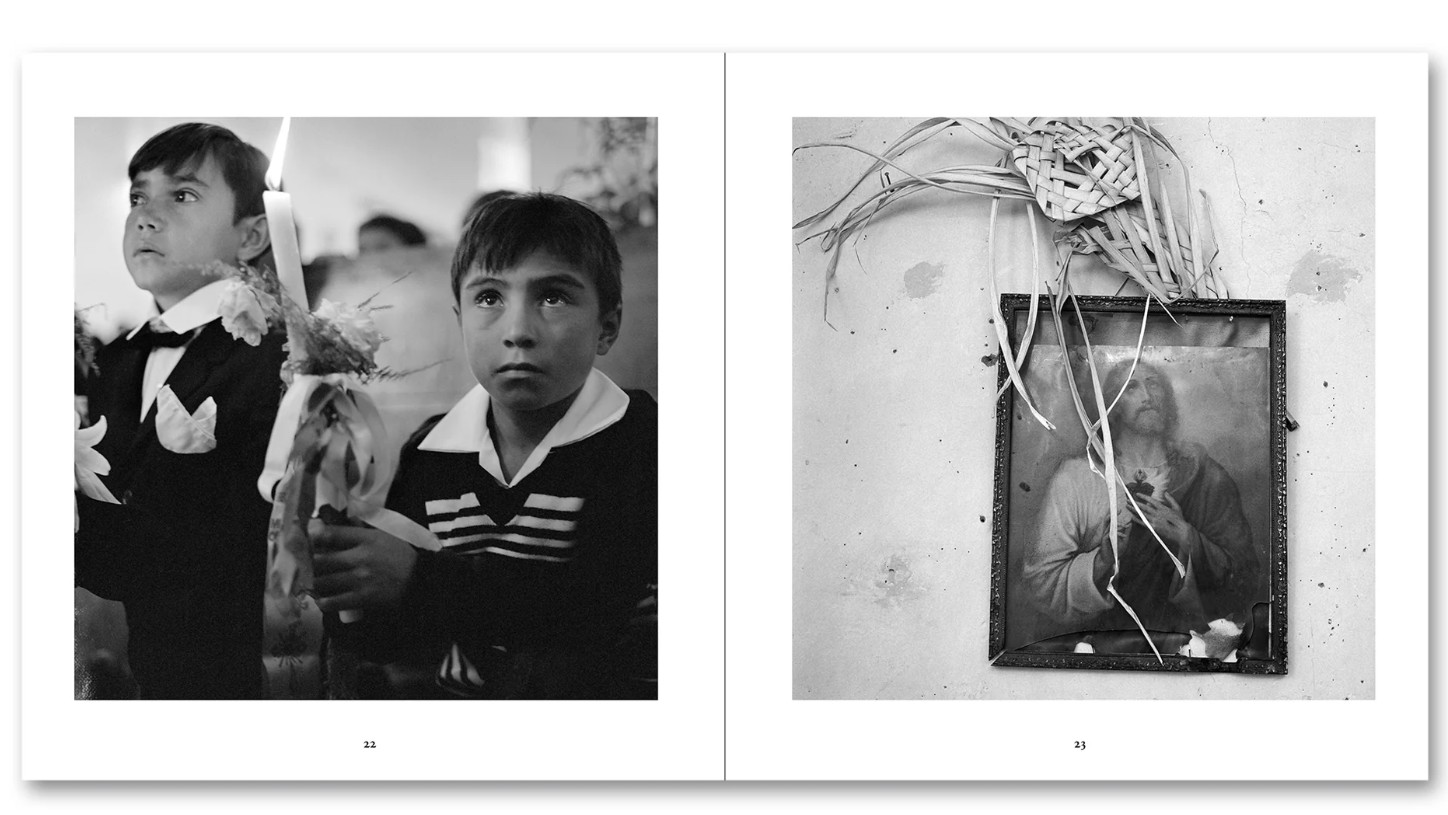

There's something profoundly satisfying about the ritual of pulling a record from its sleeve. And similarly, there's something magical about the weight of a book in your hands, the smell of fresh ink, the deliberate pace of turning actual pages.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

Because let's be honest: social media has warped our view of photography. We've trained ourselves to consume images at the speed of light, scrolling through hundreds of photographs in the time it used to take to properly examine one.

The average Instagram user spends 1.7 seconds looking at each image on their feed – 1.7 seconds. That's barely enough time to register what you're looking at, let alone appreciate any artistic merit.

This frantic consumption has created a peculiar problem: photographers are producing more images, but they're being seen less. Your carefully composed street photography gets the same fleeting glance as someone's blurry photo of their breakfast. It's the ultimate levelling down, where everything becomes equally disposable.

A photograph book says "slow down, you manic scrolling lunatic". It forces viewers to engage at a human pace, to actually look at what you created, rather than merely registering its existence before swiping to the next dopamine hit.

And so we arrive at something that sounds almost absurd in 2025: the radical act of holding something in your hands. We've become so accustomed to experiencing everything through screens that physical objects have taken on an almost subversive quality.

Rebels against the algorithm

Inevitably, photobooks are now becoming collectible. Limited editions by emerging photographers are selling for serious money, and established photographers are finding that their book projects can be just as lucrative as their print sales.

It all feels like a rebellion against the tyranny of the algorithm. On social media, your reach is determined by opaque systems designed to maximise engagement rather than quality. Your best work might be seen by 12 people while your throwaway iPhone snap goes viral. It's maddening.

But a photobook exists outside this system entirely. Its success depends on the quality of your work, the thoughtfulness of your curation, and your ability to connect with your audience – not on whether you've correctly gamed the latest Instagram update.

In a world where everything is optimized for maximum shareability, photobooks reward depth over virality; considered craft over algorithmic manipulation. Long may their popularity continue to grow.

You might also like…

Take a look at the best books on photography and the best coffee table books on photography, along with the best books on portrait photography and the best books on landscape photography

Tom May is a freelance writer and editor specializing in art, photography, design and travel. He has been editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine. He has also worked for a wide range of mainstream titles including The Sun, Radio Times, NME, T3, Heat, Company and Bella.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.