New book Hidden shows why animal photojournalism really matters right now

This emerging genre focuses on humankind’s relationship with nature – and these images are not for the faint-hearted

“Animal Photojournalism is extremely urgent and relevant to the issues of today,” says Jo-Anne McArthur, an award-winning Canadian photographer, journalist and campaigner.

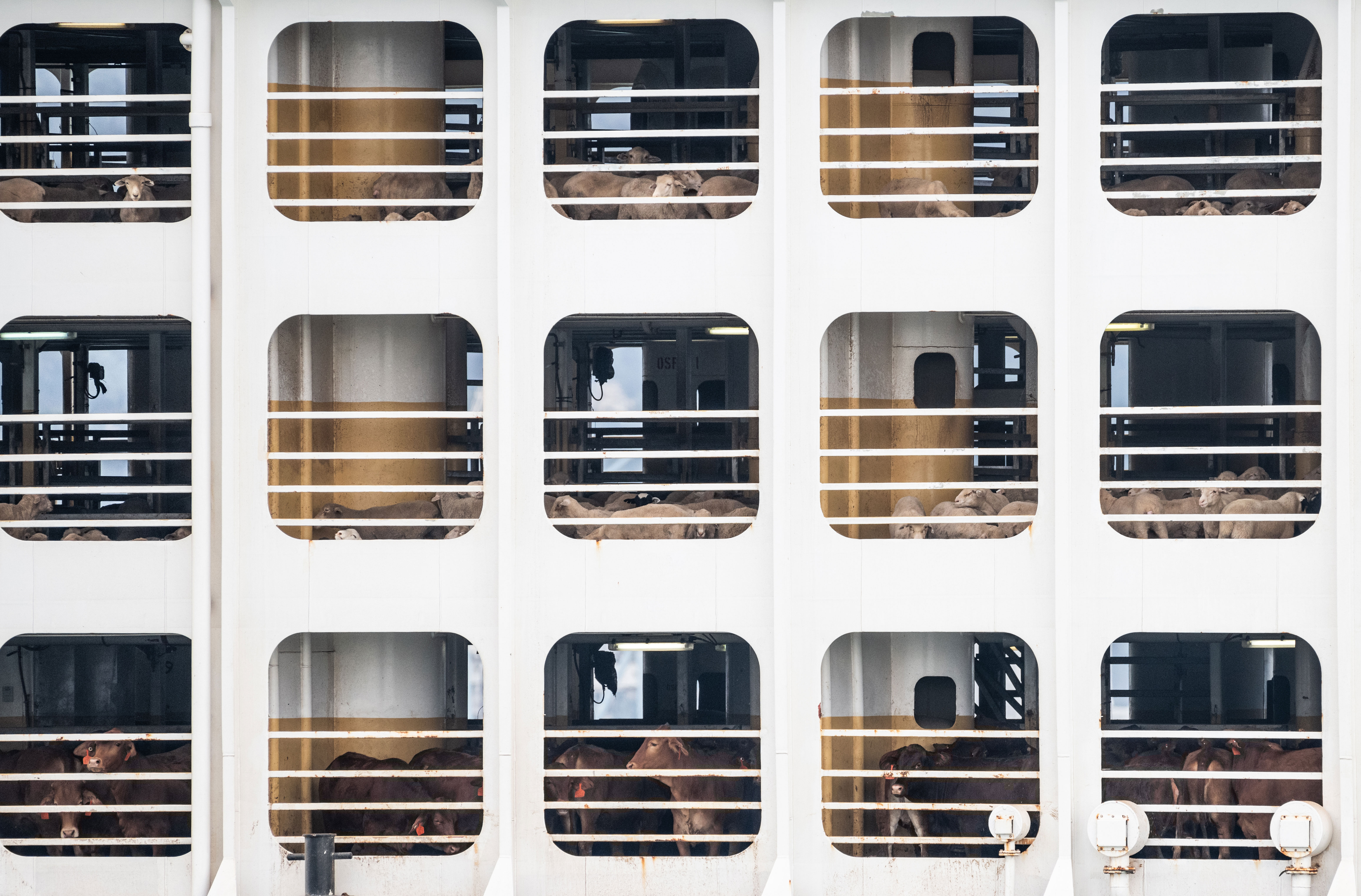

She has coined the term Animal Photojournalism (APJ) for an emerging genre of photography that focuses on people’s relationship with nature and highlights the suffering of billions of animals on the planet from human activities, including factory farms, breeding facilities and animal experimentation.

The abuse of nature isn’t just bad for animals; it’s impacting all of our lives, from climate change to the global pandemic (said to have come from bats or pangolins in China’s wildlife markets). McArthur is also the author of Hidden: Animals In The Anthropocene and the founder of We Animals Media.

We sat down with her to discuss animal photojournalism, and why it is so important.

How do you define Animal Photojournalism?

I call it an emerging genre, coming out of a number of different kinds of photography. Wildlife photography became a lot more about conservation photography, but conservation photography still excludes a number of animals, namely domestic animal and the billions of animals in labs and factory farms.

Because these animals are sentient and relevant, Animal Photojournalism likes to include all of them. That’s why we call them the ‘hidden’ animals, - they’re hidden from the public conscience, hidden from the media. We’re trying to bring those animals and stories forward.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

It's also a mix of a bit of conflict photography and street photography.

Animal issues are affecting everyone on the planet. Do you see APJ as a growing area?

Yes, that’s why I wanted Animal Photojournalism to mean something in its own right. Journalism is usually newsy and timely. I wanted to define it as its own thing and as something that overlaps with other current important issues.

For example, factory farming contributes to climate change, it overlaps with labour rights, it overlaps with human health issues and with the pandemic right now, which is caused by our animal use. That’s all part of the definition.

Who would you flag as great examples of animal photojournalists?

There’s a Spanish photographer who goes by the pseudonym Aitor Garmendia. He’s won a number of awards and won in the World Press Photo awards this year in the Environment category for his investigations of pig farms.

And there’s a Polish photographer, who also uses a pseudonym, Andrew Skowron. These guys are absolutely relentless and tireless in their work. They produce a lot of investigative work that’s been used by NGOs globally.

Many photos by you and other animal photojournalists are disturbing to look at and many people will want to turn away. How challenging is it as an area to work in?

Yes, we’re not producing images for people’s walls. They sometimes end up on walls at exhibits on the topic.

But these images are largely for campaigners. They’re for the education of the general masses. We want them to end up in major media outlets.

That’s our piece of the puzzle, when it comes to changing things for animals. Journalists are out there to show the public what’s happening behind closed doors. We often provide material evidence for NGOs to show the public.

These photos need to communicate a story or a message and need to be visually striking. What is your creative approach and how do you balance those elements?

We can talk about an individual image or a narrative. Photojournalists are working on both. We want a storyline. We want to show the big picture.

What’s really interesting about animal industries is that these animals are being farmed in the billions every day. We can go into a hen farm or a boiler chicken farm, and we might meet 900,000 birds in all the barns. It’s absolutely insane. So we want to show scale, whether that’s with a drone or with the wild angle.

But then we also want to show the individuals who make up those millions. As with war photography, we can relate much better when we make eye contact with an individual, seeing their suffering up-close through the lens.

A lot of my most relatable images have been ones where I’m actually up-close with an animal, with a wide angle, so I’m showing the individual looking at me, but also showing the context and situation this animal is in.

Is this photography that’s all about having an impact?

I wish I could hold up an image of animal torture to people and have them say, “Oh my God, I’m never doing that again.”

But people don’t do that. People are defensive and very attached to the way we do things. I understand that.

That’s why it’s important to have context and narrative, working with NGOs, giving solutions… It’s not just about the field work.

‘Hope In A Dark Forest’, your photo of an Eastern grey kangaroo and infant in Australia’s forest fires, won the Man & Nature category in Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2020. Was that a difficult photo to get?

I knew that photo was going to be a killer picture before I shot it. It’s in an eucalyptus plantation, so everything was in rows.

Through the diagonal rows I could see that the kangaroo was there, and I started walking towards the angle I wanted.

I wanted to shoot straight down through the plantation. I could see the colours and the quality of the light, her fur, and I was thinking “Oh no, oh no”, in case she moved. I got to where I needed to be and she stayed there and just watched me. I took a picture but I knew the picture I wanted was if I was more eye-to-eye, so I crouched down. I had time to get a few photos, then she bounced off.

It was one of those moments when you want to put that image on your hard drive and in the cloud and back it up a few times because you know you captured a poignant moment.

Sure enough, other people agreed. That photo is quite well-known now. It has been used and printed the world over.

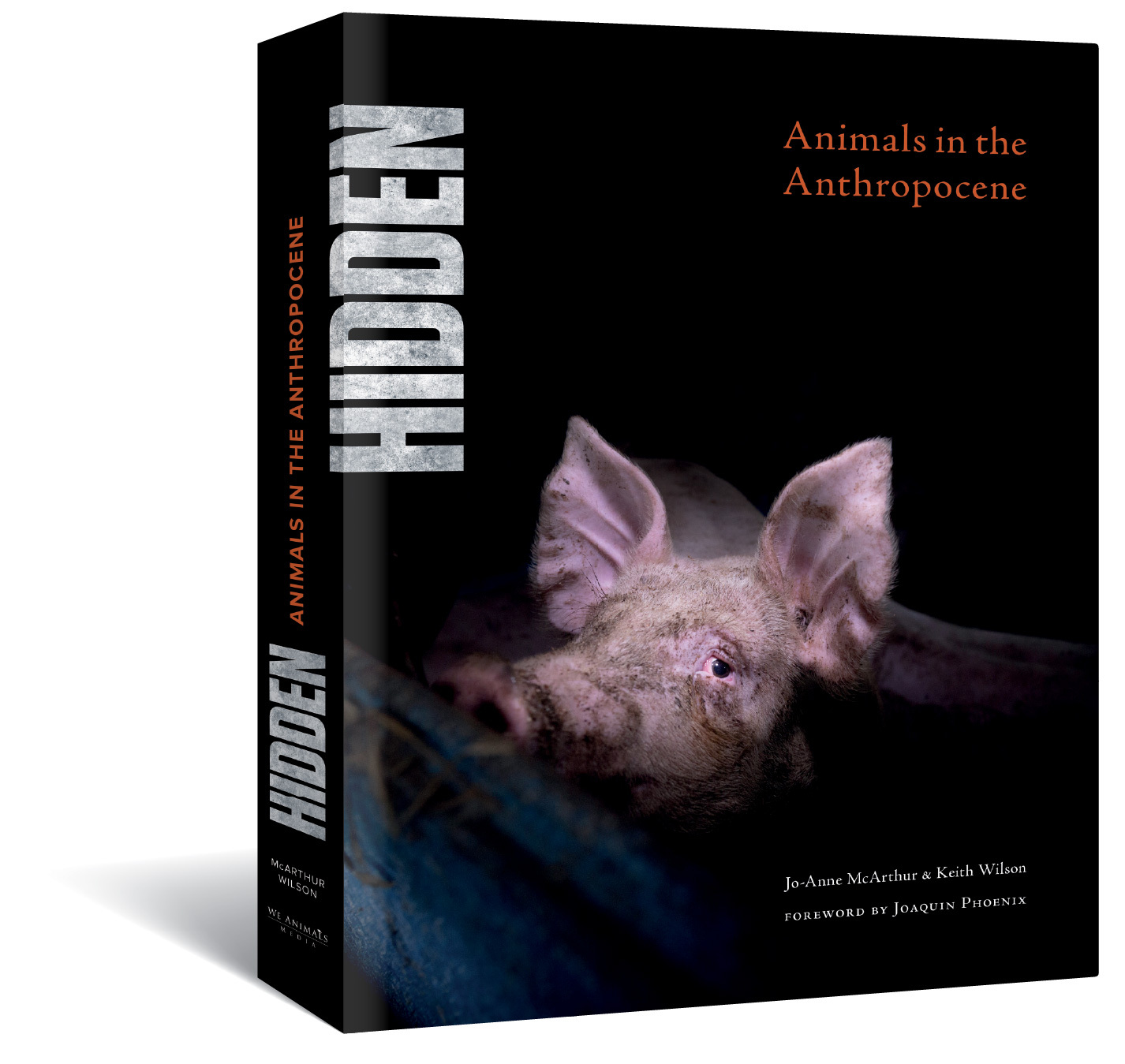

Hidden: Animals In The Anthropocene is on sale now

Featuring images by 40 animal photojournalists and a foreword by Joaquin Phoenix, Hidden: Animals In The Anthropocene by Jo-Anne McArthur, is on sale now and is published by We Animals Media.

For more about Jo-Anne’s work, click here.

Jo-Anne also co-founded Unbound, a multimedia documentary project highlighting women in conservation.

Read more

See the Nature Photographer of the Year 2020 winners