Monochrome sensors are not a joke

Rumors suggest Pentax may produce a ‘monochrome’ version of the K-3 Mark III. Right now, if you’re laughing, you’re wrong

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

But what is the point of a monochrome sensor, as rumored for the Pentax K-3 Mark III? Surely, you could just desaturate the colors in a regular image and get the same result? Not quite.

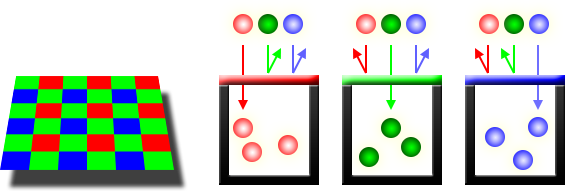

The color sensors in digital cameras are OK for black and white photography, but only up to a point. The photosites on sensors are not actually sensitive to color, only light intensity. The only way to make them capture color is to construct a color filter array (CFA) of red, green and blue micro-filters on top so that each photosite can only register these colors.

These are almost always arranged in a regular ‘bayer pattern’ of one ‘red’, one ‘blue’ and two ‘green’ photo sites in a regular 4x4 grid repeated across the whole sensor. The reason green is used twice is because the human eye is most sensitive to resolution in the green part of the spectrum.

Different makers have tried different variations on this bayer pattern from time to time, such as Fujifilm with its more ‘random’ X-Trans pattern, but the point is that almost all camera sensors use a single layer of photosites and a color filter array.

This means that each pixel will only have red, green or blue data, which is obviously no good, so the camera (or your raw processing software) then ‘demosaics’ this data to figure out the missing color values from surrounding pixels so that each one now has a full color value.

This is digital interpolation, basically, but we’ve got so used to it, and it’s now so highly developed that we don’t notice… until we try to convert a color image to black and white. That’s when the trouble starts.

Why color channels are NOISY

When you work only in color, you won’t know that the image’s individual RGB (red, green and blue) color channels are compromised by the limited data for each and the interpolation process used to ‘reconstruct’ the full color data. When you’re working in color, each pixel is usually an amalgam of two or three color channels, so they kind of help each other out.

The best camera deals, reviews, product advice, and unmissable photography news, direct to your inbox!

But black and white is not so forgiving. It’s OK if you don’t attempt any heavy channel mixing or similar techniques to emphasise one color channel and pull back another to simulate the effect of black and white ‘contrast’ filters (like a red filter to deepen blue skies, say). But if you do, and especially if you push it too far, you realise that your images can quickly turn noisy and blotchy, with noticeable edge artefacts.

This happens when your adjustments lean too heavily on the red channel (created with only one pixel in four in a bayer sensor layout) and the blue channel (also only one pixel in four) for your adjustments. These are the two color channels needed to recreate the red and yellow filter effects so widely used in black and white.

So why didn’t this happen with film?

Because black and white film is sensitive only to black and white. If you put a red, yellow or green filter over the lens, the sensitivity to those colors would be altered, but each ‘grain’ of film would still be exposed and developed as normal.

With a bayer sensor, if you use a red, yellow or green filter, you’re effectively blocking, or switching off, a whole bunch of photosites. In fact, with digital cameras there’s probably not much difference between using black and white filters and doing digital ‘channel mixing’ later – both lean heavily on a smaller set of data in your captured image, and both will show a kind of degradation you would never have got with black and white film and black and white filters.

This is why black and white sensors are important

Leica didn’t make the M10 Monochrom and Leica Q2 to squeeze more money out of a gullible public. It did it because that was the only way to get proper black and white image quality, especially for those who want to use black and white filters.

It’s not just Leica. Phase One makes a fabulously expensive 151-megapixel Achromatic camera back because it’s the only way to get the fabulous black and white images it’s capable of. Red Cameras makes its DSMC2 Monochrome Brain cinema camera for the same reasons.

So if Pentax (according to rumors) wants to make a monochromatic version of the Pentax K-3 Mark III, we’re not going to snigger, we’re going to applaud. Pentax may not quite have its finger on the pulse of the latest imaging trends (sorry, Pentax), but it does understand what image quality means and what it takes to achieve it.

The digital black and white dilemma

1. You can shoot with a regular color camera and accept that you can’t push channel adjustments too far.

2. Or you can shoot with a black and white camera and accept that you will need to use filters – there is no color data to achieve the same thing digitally.

In reality, if you’re sensible with your channel adjustments, a color sensor can still produce great black and white images. There’s more than one way to work in black and white, and a bit of dodging and burning or a graduated filter can darken a blue sky just as effectively as a red filter.

Rod is an independent photography journalist and editor, and a long-standing Digital Camera World contributor, having previously worked as DCW's Group Reviews editor. Before that he has been technique editor on N-Photo, Head of Testing for the photography division and Camera Channel editor on TechRadar, as well as contributing to many other publications. He has been writing about photography technique, photo editing and digital cameras since they first appeared, and before that began his career writing about film photography. He has used and reviewed practically every interchangeable lens camera launched in the past 20 years, from entry-level DSLRs to medium format cameras, together with lenses, tripods, gimbals, light meters, camera bags and more. Rod has his own camera gear blog at fotovolo.com but also writes about photo-editing applications and techniques at lifeafterphotoshop.com